While the final two episodes of Danger Man were still in post, pre-production was already underway for Patrick McGoohan’s new project The Prisoner. He had quit Danger Man as the highest paid television star in the U.K., one whose popularity crossed the Atlantic; his contract was up, and he had no interest in continuing the adventures of secret agent John Drake, bringing its fourth series to an abrupt close. The Prisoner would be something quite different – a high-concept science fiction scenario in which its Drake-like protagonist, an agent who resigned for unexplained reasons, is transplanted against his will into a fortified community and questioned relentlessly about his reasons for resignation in an attempt to break him. Despite his resourcefulness and iron will, he would fail to escape his mysterious captors at the end of each episode. Though the press materials would claim that the idea originated entirely with McGoohan, Danger Man script editor George Markstein, who would take the same role on the new series as well, was likely responsible for the premise of “The Village,” the genial-looking prison at the center of the show. Markstein had heard of a location in Scotland where “recalcitrant agents” were placed in order to stop them from defecting. McGoohan, taken with the idea, further fleshed it out with producer David Tomblin. They envisioned a Village where our hero would be trapped, its quaint appearance hiding an elaborate surveillance and security system. McGoohan found the perfect location in Portmeirion, the peculiar North Wales village built by architect Clough Williams-Ellis, its collection of features assembled from across the globe lending it a perplexing and cosmopolitan appearance. If you didn’t already know Portmeirion, you were unlikely to guess where this Village could be found. McGoohan pitched the premise to ITC’s Lew Grade, who was about to lose his Danger Man star if he didn’t accept. The actor later recounted in an interview with Alain Carrazé, “He didn’t like reading scripts, but preferred to hear the idea, to see it in his mind’s eye. After listening to the bizarre concept, he took a few puffs on his cigar, walked around the office a couple of times and said, ‘It’s so crazy it might work. Let’s do it. Shake.’ And we did. He gave me carte blanche. I was very fortunate.”

Patrick McGoohan in the opening credits for “The Prisoner.”

A number of elements came together to make The Prisoner so distinctive from its predecessor as well the rest of the TV landscape. Most prominent was McGoohan himself, who took a firmer creative hand on this program than Danger Man, acting as executive producer and utilizing his own production company, Everyman Films Ltd. He also wrote and directed critical episodes of the series, exploring his own ideas on individualism, society, politics, and the nature of progress. While McGoohan’s episodes contained a philosophical bent, often written like avant-garde theater, the more grounded Markstein pulled the series in the direction of twisty spy thriller, albeit one with overtly fantastical elements. The writers hired to produce scripts seemed to land at every point in-between these two poles, with varying degrees of success. But also key to the show’s memorable quality was its instantly iconic look, courtesy art director Jack Shampan. Shampan was tasked with creating a world out of whole cloth, while imposing a uniformity in costume and production design that one might associate with dystopian SF novels. Consider that this is a show whose font is famous. The nameless Villagers wear colorful striped clothing and proudly display their numbered badges. Against this sea of conformity, the Prisoner is striking in his simple black suit (he never wears his badge). Beneath and beyond the cheerful resort exteriors of Portmeirion are the cold, ominous chambers where No.2 and his staff observe the Village, like Ken Adams’ Strangelove and Bond sets on a higher-than-average TV budget. Metallic hallways, chilly rooms draped in boxy electronics and wires, doors with portholes to hellish lobotomizing interrogation techniques, lush purples and bloody reds, giant screens with psychedelic lava lamp screensavers, tables of globes and walls lined with maps of the Village – this is the authoritarian inner world ruled by “No.1,” whose presence is only suggested by a free-standing red phone.

In “Arrival,” No.6 (McGoohan) meets his first No. 2 (Guy Doleman).

This strangeness is pushed into the outright surreal with the introduction of Rover, the Village guard dog – a bouncing white balloon that captures its targets by absorbing them. Both Rover and the ubiquitous penny-farthing bicycle every Villager wears on their badge have become the indelible symbols of The Prisoner, almost as widely recognized as the theme song to The Twilight Zone. The show produced seventeen episodes, its series finale airing just four months after the premiere. McGoohan later said in an interview with New Video Magazine, “We started out with seven scripts with no intention of expanding it further. Lew Grade wanted twenty-six scripts. I didn’t believe the concept could be sustained over that period. We finally did seventeen episodes…The original concept was completely expressed during its television run.” Though its McGoohan-masterminded conclusion brought controversy and resentment among viewers who felt cheated of a more straightforward climax, The Prisoner was bound to become a legend of genre TV. Portmeirion still hosts Prisoner fans year-round and maintains the Prisoner Shop. An episode of The Simpsons was devoted to parodying the show. Graphic novels, board games, an audio drama, and a miniseries remake have all arrived over the decades. Through its stubborn refusal to be categorized or easily defined, the show has carved out its own corner of pop culture. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be taking a closer look at each episode, its production, its themes and imaginative contributions to the ambitious scope of The Prisoner.

ARRIVAL First UK Broadcast: September 29, 1967 [episode #1 in transmission order] | Written by George Markstein and David Tomblin | Directed by Don Chaffey

SYNOPSIS

Over opening titles, a secret agent (McGoohan) races his custom Lotus 7 beneath a stormy sky. He drives into London, turns into an underground garage, strides down a dark corridor, and furiously presents a letter of resignation to a man behind a desk (script editor George Markstein, in a cameo). Machines “x” his photo out of the system and file him under “RESIGNED.” As he packs luggage in his London flat, mysterious top-hat wearing men drive up in a black car and gas him through the keyhole. He awakens seemingly in his own residence – but when he opens the curtains, he sees that he’s actually in the Village. Here everyone refers to him as No.6 and wears a badge declaring their own number. He phones up a taxi (a Mini Moke that zips up and down the narrow paths). The driver at first speaks French to him before realizes he’s English. He wants to leave this place, but she says they only provide local service; she drives him in a circle around the Village. At a store, he buys a map, but it doesn’t extend beyond the perimeters of the Village, with the borders noted as “The Mountains” and “The Sea” and “The Beach.” Someone calling himself No.2 phones No.6 and asks to meet at his residence, the Green Dome, to provide answers.

No.6 finds himself in the Village for the first time.

In the Green Dome, No.6 is greeted by a mute dwarf butler (Angelo Muscat) and is escorted into a circular chamber where the umbrella-wielding No.2 (Guy Doleman, Thunderball) sits in a globe chair that rises out of the floor. No.2 won’t reveal for whom he works, but after demonstrating that he knows everything there is to know about No.6 – that is, except his time of birth – he explains that he is tasked with learning why No.6 resigned. “The information in your head is priceless. I don’t think you realize what a valuable property you’ve become.” He takes No.6 on a tour of the Village, where No.6 first encounters Rover – a giant white ball that explodes out of a fountain and consumes one of the Villagers. He also shows No.6 other sites, including the Labour Exchange, where the locals are assigned jobs to keep them content during their permanent stay. An early escape attempt on the beach leads to Rover incapacitating him, and he recovers in the hospital, where patients are routinely lobotomized. Here he finds his old friend Cobb (Paul Eddington, The Adventures of Robin Hood), whom the Village has also abducted and interrogated for his secrets. After No.6 visits with him, he’s told that Cobb has committed suicide by jumping out the window.

The Admiral advises, “We’re all pawns, m’dear.”

Cobb’s funeral procession is the cheerful Village marching band, and he’s buried in the Village graveyard at the beach. No.6 observes that one of the onlookers (Virginia Maskell, Doctor in Love) is in tears, so he reaches out to her as a trustworthy confidante. She explains she was a friend of Cobb’s and that together they were plotting an escape via stolen helicopter, bypassing Rover by using an “electropass,” a high-tech Hamilton watch. No.6’s trust wavers when he sees her leaving the Green Dome, but he follows through with the escape attempt anyway. He’s able to walk past a docile Rover and get the Village helicopter into the air, but No.2, who is watching from a control room, steers the helicopter back down onto the helipad. Beside him is a perfectly healthy Cobb, who is about to leave the Village to report to “new masters.” He declares there are no loopholes in the Village’s security and advises him, “Don’t be too hard on the girl. She was most upset at my funeral.” As for No.6: “You’ll find him a tough nut to crack.”

Rover shepherds a bitter No.6 at the conclusion of “Arrival.”

OBSERVATIONS

When evaluating the best episodes of The Prisoner, it would be a shame to overlook “Arrival” on the basis that it’s scene-setting. Although this first episode mostly holds back on the surreal excess, satirical commentary, and espionage drama that will come to characterize the show, it is nonetheless blessed with the job of revealing the show’s fantastic and compelling premise. The opening credits – of which we only receive half for this time around, since what will become the second half of the credits are actually this episode’s entire plot – are edited together as a succession of fevered images, each lasting scant seconds. It’s said that McGoohan himself had a hand in editing, just as he asked theme composer Ron Grainer (of Doctor Who fame) to kick the music into something more bombastic and literally thunderous. The mystery of “What is this place and who runs it?” is the focus of this first outing. The fact that no real answers are provided, and that No.6 remains imprisoned at the close of the episode, may have shocked or turned off many viewers who expected Danger Man. Yet it’s told in the most entertaining way imaginable. His initial interactions with the Villagers – the taxi driver and the general store owner – are just as amusing as they are baffling. (When No.6 asks for a bigger map, the shop owner merely provides the same map printed larger.) The Village also contains overt suggestions of something more science-fiction underway in the premise: the wireless phones and automatic sliding doors in his house; the futuristic-looking “Free Information” board in the town square; Rover; the fact that the Villagers freeze on command; No.2’s chamber and the control center where the Supervisor watches the security cameras; the sinister interior of the Hospital, and so on. The viewer is compelled to keep watching to find out just what the hell is going on.

George Baker as “the new No.2.”

Publicity materials point out that the Village could serve one of two purposes. One is to break him and learn his secrets. They quote McGoohan: “He has secrets they want to get out of him. What isn’t so clear, though, is if this is just a method of training him to top indoctrination resistance…to see how far he can go without breaking.” Certainly an obvious explanation is that No.6’s captors are those from whom he just resigned; both of the very British No.2’s in “Arrival” suggest that No.6 giving in to their demands is no more than helping fill out some necessary paperwork. But it’s the principle of the thing. (This, by the way, is the “reason” No.6 resigned, as No.2 states it – “principle.”) No.6 is a prisoner. He owes them nothing and deserves his freedom. The brilliance of The Prisoner is that it pushes the concept further: No.6 deserves his individuality in the face of conformity and societal oppression. As we will soon learn, the Village wants to take everything from him, including his own identity. But No.6 is indeed a “tough nut to crack,” suspicious of most everyone, including his rotating roster of maids (a running joke that begins this episode). It is a battle of wills for the ages, and “Arrival” establishes the stakes in one of television’s most entertaining hours.

6 OF 1…

When asked why he chose the number 6, McGoohan pointed out that the number is unique in that it becomes a different number when turned upside-down. (Shades of “The Schizoid Man“?) There are suggestions that No.6 is John Drake. The earliest script drafts supposedly refer to No.6 as Drake, and the photo which is filed under “Resigned” is actually a promotional photo of McGoohan as Drake. But one could also argue that 6 is McGoohan. The date of the Prisoner’s birth – March 19, 1928 – is the actor’s.

THE WARDERS

This episode establishes that No.2 is a constantly revolving office; No.6 is bemused halfway through the episode when Guy Doleman is abruptly replaced by George Baker. Baker offers no explanation, and the topic is dropped as the conversation returns to the same push-and-pull between the individual and the authoritarian.

Cobb will be the first of a handful of characters introduced from the Prisoner’s life before his abduction, although we learn little about him except that he was a fellow agent and now serves the Village (although, as the episode ends, he is transferred to some other, unknown entity – perhaps another Village?). I don’t make much of some fans pointing out that “Cobb” is an acronym for “Chimes of Big Ben,”one of the best loved episodes of the series.

The failed prototype for Rover is assembled on top of its driver.

Rover was originally intended to be a vehicle with a dome-shaped hood and a flashing blue light which could travel by both land and sea, like a hovercraft. A test model was built which proved a disaster to drive, and frankly looked like a blancmange on wheels. There are various reports of the origins of the balloon design for Rover, but the most reliable account is that it was Production Designer Bernard Williams alongside McGoohan. In the documentary Don’t Knock Yourself Out, Williams states that he and McGoohan saw weather balloons floating in the sky during production and reconceived Rover thus. Rover was guided along by wires, and sometimes the film was played in reverse while Rover was pulled, which is one explanation for why the Villagers freeze in place at No.2’s command. Which brings us to…

THE VILLAGERS

One of the curiosities of the Villagers is that their portrayal can vary from episode to episode, or sometimes within the same hour, as is the case with “Arrival.” It is either the case that (a) the Villagers are individuals suffering under an oppressor (or, alternately, enjoying their incarceration); or (b) they are an unthinking mob capable of demonstrating bizarre behavior and nightmarish groupthink. Here the fact that the Villagers suddenly freeze in their tracks at the barked order of No.2 suggests they might not even be real people. Another odd detail, which “Arrival” lingers on: the electrician who comes to fix No.6’s speaker has a lookalike working as a gardener, suggesting that they might be clones. (The series doesn’t really pursue this idea much further, leaving it as another note of strangeness to unsettle the viewer.) In another curiosity, the Village shopkeeper is speaking in Italian to a customer as No.6 enters, but he immediately switches to English, as if for No.6’s benefit. All these details keep the viewer off balance from one scene to the next, contributing to the show’s dream-like quality (and setting the stage for the more outlandish episodes to come). But of course No.6’s maid, the duplicitous Cobb, and the woman with whom No.6 conspires to escape are all recognizably human characters.

The Admiral is No.66, which is also the number of No.6’s maid. The number appears again on a taxi driver as No.6 leaves the Hospital. One could assume the production department hadn’t caught up on the demand for numbered badges yet, but otherwise you can let the conspiracy theories fly. (There are other “flubs” in the episode, chronicled on various sites, but this seems to be one of the most glaring.)

On a side note, who are those frolicking girls in bikinis and why are they in the Village?

THE VILLAGE

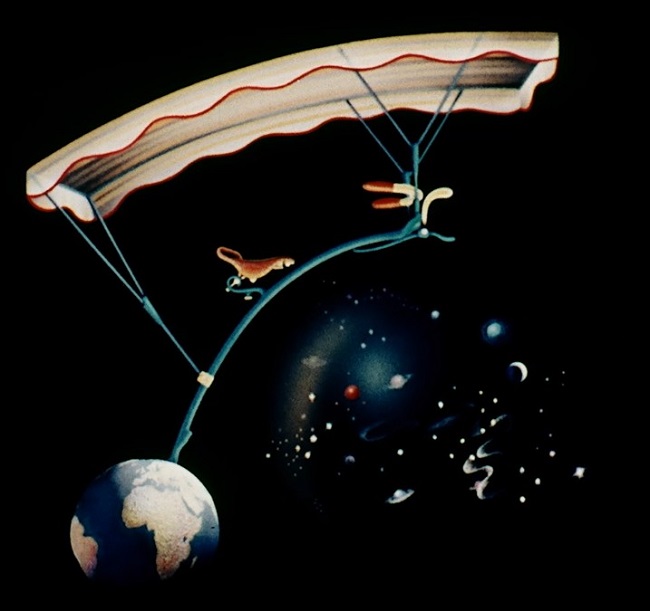

Penny-farthing bicycles appear prominently, either in the background of shots, hanging about offices, or, in one scene, front and center, as the camera zooms in on the bicycle before a Villager pushes it away. McGoohan later stated these represent “progress.” In the original end-of-show tag (which can be seen in the alternate early cut of “Arrival”), an image of the Earth in relation to the universe resolves itself into a penny-farthing. In the early cut of “The Chimes of Big Ben,” a significant variation of this imagery occurs: the Earth and the universe linger for a moment, the Earth rotating; then the universe unfolds against the background, the Earth zooms in close to the camera and a single word appears against a bright red backdrop: “POP.” Apocalyptic, no? Note that “Pop Goes the Weasel” is played on the soundtrack of this episode, as it does in other episodes.

The original penny-farthing post-credits image of “Arrival.”

Lava lamp bubbles appear on No.2’s screens in his chamber, but you can also see lava lamps in No.6’s domicile and as unusual furnishings for the Hospital.

I’ve always found it slightly disturbing (if visually striking) that the cemetery is on the beach. Of course the implication is that you will spend your whole life in the Village, from playing by the “Free Sea” (fountain) and the Stone Boat (which can never sail) to retiring in the Old People’s Home (playing chess by yourself) until you are finally laid to rest in the Graveyard. But it only takes a deep tide to wash your body out to sea. Maybe then you’ll finally be liberated from the Village?

FISTICUFFS

It wouldn’t be The Prisoner without a fistfight. Here it occurs on the beach between No.6 and some Village guards. Expect a fistfight to be randomly inserted into upcoming episodes when the conflict threatens to be too…intellectual.

WIN OR LOSE?

I’ll start keeping track of who wins each metaphorical game of chess in these episodes. For “Arrival,” No.6 most certainly loses.

METHODOLOGY

The Village’s assault on No.6 in this episode is fairly basic: a mole (Cobb) influencing another person (the Woman) who influences No.6. But the only point is to prove to No.6 that he cannot escape. They haven’t yet tried to really break him.

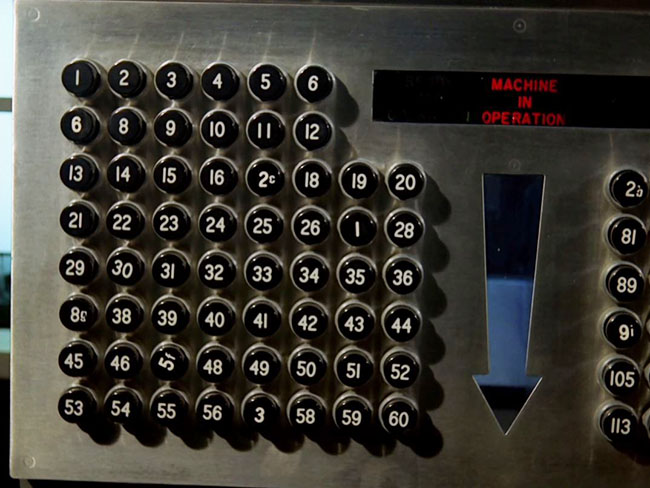

The Free Information board and its curious numerology.

NUMEROLOGY

The Free Information Board seems to follow its own mystery code: there is no 7. Freeze-frame on the Prisoner’s credit card and you’ll see it also lacks the “7” in a sequence of numbers. One wonders if McGoohan originally intended to do more with this idea, or if there really is some buried meaning. Then again, maybe they were just short on sevens when they were being handed out that day?

PROPAGANDA

In the Labour Exchange we get a litany of slogans hung on the walls: “Humour is the Essential Ingredient of a Democratic Society.” “Of the People/By the People/For the People.” “A Still Tongue Makes a Happy Life.” “Questions Are a Burden to Others, Answers a Prison for Oneself.”

All signs – “6/Private,” “Walk On the Grass,” “Welcome to Your Home From Home” – are in the standard Village font, which is related to the Albertus family, for the record. Most notably, the “i”s aren’t dotted and the “e” is written like a capital letter, but rounded like a lowercase “e.” It’s a font worth fetishizing.

No.6 steals the Village helicopter.

SEQUENCE

Here we come to the Great Debate: In what order should the episodes be placed? The original U.K. broadcast order is the “official” sequencing, but it varies from the U.S./Canadian broadcast order. This wouldn’t be such a controversy except that the episodes themselves offer clues that both the U.K. and North American broadcast orders have errors – for example, placing “Dance of the Dead” eighth and “Checkmate” ninth when the dialogue in both episodes make it clear that No.6 has only recently arrived. You might ask – why not just follow the order in which the episodes were produced? This is not foolproof either: “Once Upon a Time,” which is the first installment of a two-part series finale, is actually production episode #6. Over the decades, various alternate episode sequences have been proposed based on hints given in the episodes or to simply improve the overall arc of the Prisoner’s story. Some have also suggested that episodes with Portmeirion footage should be dispersed evenly throughout one’s viewing, to avoid watching so many studio-bound episodes in a row (which naturally happens when you watch them closer to their production order). Six of One, the official Prisoner Appreciation Society, has their own official sequence, which was utilized on the A&E DVD sets. Tim Lucas of Video Watchdog published his own preferred order several years ago. The debate rages on.

Here is the U.K. broadcast order, which is the closest we have to “official.” It’s fine for a viewing experience. Really. I’m not judging.

1: Arrival

2: The Chimes of Big Ben

3: A. B. & C.

4: Free for All

5: The Schizoid Man

6: The General

7: Many Happy Returns

8: Dance of the Dead

9: Checkmate

10: Hammer Into Anvil

11: It’s Your Funeral

12: A Change of Mind

13: Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling

14: Living in Harmony

15: The Girl Who Was Death

16: Once Upon a Time

17: Fall Out

But I will add to the debate with my own order, which balances clues in the script, the production order, and the telling of The Prisoner as one long story. Unfortunately, without violating obvious clues one is bound to end up with all the weaker episodes piled into the second half, and you will find that happening here. We only know this for certain: “Arrival” comes first, “Once Upon a Time” is Episode 16, and “Fall Out” is Episode 17. Everything else is up for grabs. I’ll let the order of these blog posts form my preferred viewing sequence.

Note that in “Arrival,” No.6’s datebook is filled out for him (how nice!) but the dates are blank, so there is no clue there to help with arranging future episodes by date.

QUOTES

Taxi driver: It’s very cosmopolitan. You never know who you’ll meet next.

No.2: Personally I believe your story. I do think it was a matter of principle.

No.6: I will not make any deals with you. I resigned. I will not be pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, briefed, debriefed, or numbered. My life is my own.

No.2: Is it?No.2: Pretty, isn’t it? Almost a world of its own.

No.6: I shall miss it when I’m gone.

No.2: Oh, it will grow on you.Village Announcer: Here is a warning. There is a possibility of light intermittent showers later in the day.

No.66 (The Maid): We have a saying here. A still tongue makes a happy life.

No.2: People change. Exactly. So do loyalties.

No.2: For official purposes, everyone has a number.

No.6: I am not a number. I’m a person.

No.2: Six of one, half a dozen of the other.The Admiral: We’re all pawns, m’dear. Your move.

UP NEXT: FREE FOR ALL