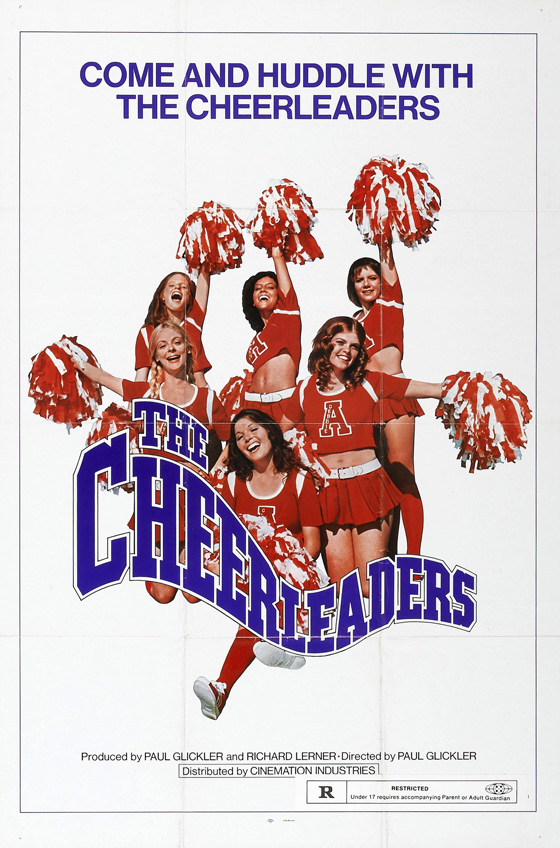

The Cheerleaders (1973) presents a MAD Magazine view of high school, one in which the football players are grunting, primitive horndogs, and the cheerleaders, far from being mere distractions by the bleachers, possess a superhero-like sexual power that proves to be the elemental force determining who wins or loses a game. It plays to the audience’s sexual fantasy – that audience being teenage boys sneaking into the theater – while sending it up. The plot: cute, innocent Jeannie (Enid Finnbogason, under the wonderful pseudonym Stephanie Fondue, and appearing in her first and only film) yearns to join Amorosa High’s cheerleading squad. The female coach is only willing to consider Jeannie because she’s a virgin; their former star “was so good she wound up in the maternity ward.” Claudia (Denise Dillaway), the squad’s captain, suggests “a cheerleader with a chastity belt.” (When Claudia first learns that Jeannie is a virgin, she says with genuine shock, “Really? I didn’t know there were any in Amorosa.”) Jeannie is recruited, but over a bet on whether she can remain a virgin through the entire football season, a task complicated by the fact that the squad seems to be involved in nonstop hanky-panky: with the boys at the car wash, with the boys at the hamburger stand, with the football coach, with Jeannie’s brother and sleazy dad, and finally, disastrously, in an orgy with the football team. Just as in Bull Durham, sex drains the athletes of their talent. Or, as Claudia puts it when she finds out: “This is our team! You fucked out our own team!” The only solution: do the same to their rivals before game day arrives. When the ref blows the whistle to start the game, both teams collapse onto the grass, already exhausted before the first play.

Gum-smacking Debbie (Brandy Woods) is on the prowl.

This is one of only three films from director Paul Glickler, the other two being a porno and a Judge Reinhold movie (Running Scared); I haven’t seen the others, but I’m willing to bet it’s the best. What makes The Cheerleaders so memorable is its Joy of Sex. Granted, there are some scenes in questionable taste, or this wouldn’t be a 70’s exploitation movie. In a hazing ritual, Jeannie is tricked into taking a shower in the boy’s locker room, and the team almost gang-bangs her before she escapes. Another scene involves Claudia and Jeannie pretending to resist the sexual advances of two leather-clad bikers, because they know these creeps only like girls who say say no. Then, of course, there’s all the sex with older, leering men. But the tone is not what you would expect. Everything is several degrees off reality, wildly exaggerated and slapstick. How does one explain that an intimate seduction scene becomes a farce involving four different players in a Scooby Doo-like chase through slamming doors, salsa music, chattering wind-up toys, a “toe job,” a bear suit, and an exploding water bed that finally sweeps our heroine out of the room in a tidal wave? The cheerleaders frequently speak in “hip,” innuendo-laden rhymes, and when perpetually out-of-step Jeannie tries to emulate them to seduce the nerdy Norman (Jonathan Jacobs), she ties her tongue into knots: “You got pies in your Levis. Keep your mule on the stool… You know why my thighs got a sty in your eye?” We learn that the town’s miniature golf course comes with its own miniature golf coach (a dwarf). In the film’s funniest sequence, the cheerleaders, realizing the folly of their orgy with the football team, spring into action, and we get a montage of the girls tracking down every member of the opposing team like succubi to the rescue: in a movie theater (showing another Jerry Gross production, 1970’s I Drink Your Blood); in a bedroom while a bodybuilder lifts weights (he’s surprised when the barbell is swapped out with a naked girl, lifting her just as effortlessly); in a car under repair at a mechanic’s (with a very suggestive hydraulic lift). It’s no surprise that when co-producer and co-writer Richard Lerner returned to the Cheerleaders franchise to direct, he gave us Revenge of the Cheerleaders (1976), a film so over-the-top that it’s practically a live-action cartoon.

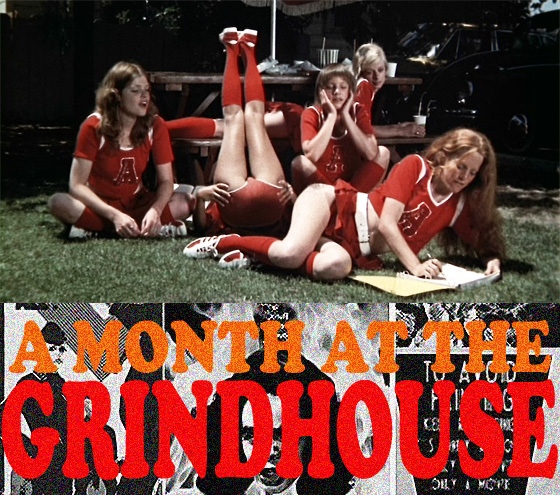

Scheming for a successful football season: Sandy Evans, Brandy Woods, Denise Dillaway, Stephanie Fondue.

The Cheerleaders gets some of its taboo kick from the fact that its story takes place in a high school rather than a college or the NFL; the girls (who don’t look quite that young) seem like real girls, not professional actresses – and most of them were complete amateurs, though they deliver their ridiculous lines with charming enthusiasm. The film was something of a guerrilla affair, non-union, and the football scenes were shot at a real high school, Monte Vista High in Danville, California (about half an hour’s drive from where I grew up). To keep the film’s exploitative nature secret from the school board, Glickler says he dragged his feet on providing them with a script, and they likely didn’t read a word until shooting was completed; only one scene, in which evil janitor Novi (Raoul Hoffnung) kidnaps two cheerleaders and drags them into a closet, raised some alarms with the school staff – even though this is one scene in the film in which Novi doesn’t have perverted intentions. When you see the spectators in the bleachers, you can see these are real families and kids excited to be extras in a movie, with no clue as to the film’s actual content. You can see suburban houses just over the low fence behind the field, even in a shot where Sandy Evans flashes a player (understandably, she’s quick about it). The more risqué material, such as the locker room scenes, were shot at Laney College in Oakland. Both schools are still around. The actress who makes the greatest impression in the film is Ms. “Fondue,” who radiates innocence in the film but proved to be the most sexually liberated in the cast (she enjoyed the groping in the locker room hazing far more than the nervous boys did). Glickler recounts that for Fondue’s big sex scene at the end of the film, she conspiratorially asked him if she could do it hardcore even though this wasn’t a porno – just as a secret they could keep from the audience, a little prank. He balked. One wonders if her co-star would have been thrilled or mortified.