HAMMER INTO ANVIL First UK Broadcast: December 1, 1967 [episode #10 in transmission order] | Written by Roger Woddis | Directed by Pat Jackson

SYNOPSIS

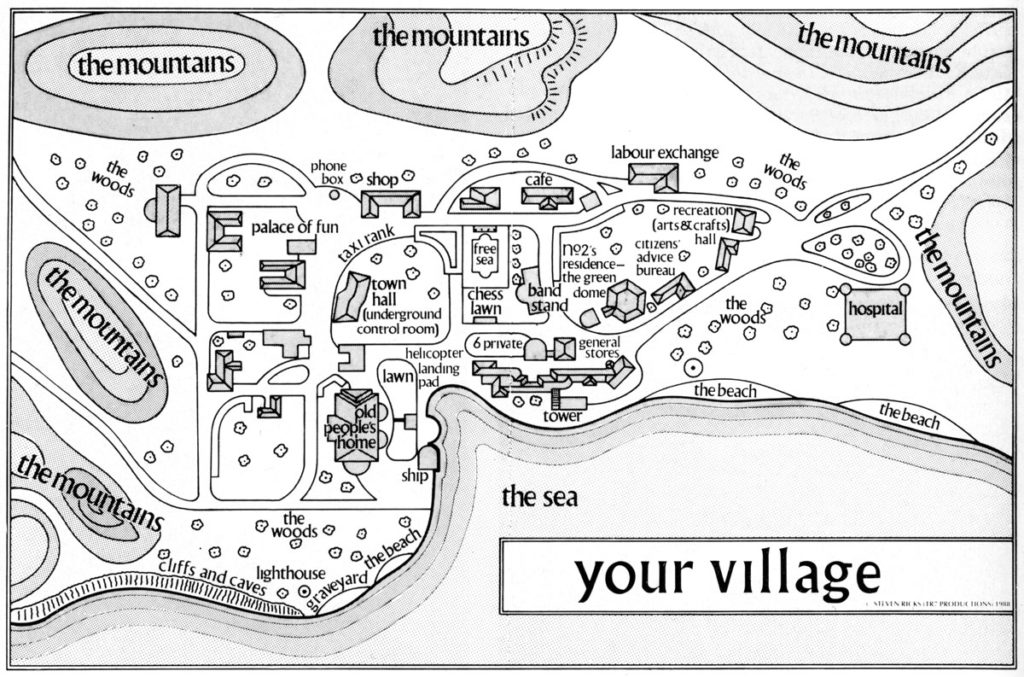

A young female prisoner, No.73 (Hilary Dwyer, Witchfinder General), is in the Hospital after slashing her wrists. No.2 (Patrick Cargill, Help!) pressures her to tell him where her husband has gone, going so far as to show photos proving that her husband has been cheating. When No.6 hears her scream, he rushes to her hospital room just in time to see her jump out the window to her death. “You shouldn’t interfere, No.6,” No.2 admonishes. “You’ll pay for this.” No.6 only glares at him and says, “You will.” Later, when summoned to the Green Dome, No.6 refuses, and thugs wheel up in a mini-moke to beat him and drag him there. No.2 is wielding a sword. He presses the tip of the blade against No.6’s brow and tells him that one must be an anvil or a hammer, assuring him that he will break him. But after the meeting, No.6 begins a campaign of unusual behavior. In the General Store, he listens to several copies of the same Bizet record, listening to only a few notes of each, checking his watch and writing something down. He leaves a copy of the Tally Ho behind (the headline: INCREASE VIGILANCE CALL FROM NO.2). The store assistant gives No.2 a copy of the paper. In the phrase “security of the community,” No.6 has circled the word “security” and written a question mark above it. No.2 later finds a hidden message written by No.6:

To X.0.4.,

Ref your query via Bizet record.

No.2’s instability confirmed.

Detailed report follows.

– D.6.

No.6 is threatened by No.2’s sword.

No.2, increasingly paranoid that No.6 is a plant, has him watched closely by his right-hand man No.14 (Basil Hoskins). No.6 leaves blank sheets of paper in the Stone Boat, and when one of his programmers cannot find any hidden messages on the pages at all, he suspects the man and has him sacked. No.6 calls a psychiatrist in the Hospital and acts as though he’s in league with him, to the man’s confusion; No.2 has him called in too and hurls accusations at him. No.6 has a quotation from Don Quixote placed in the Tally Ho which translates as “There is more harm in the Village than dreamt.” He puts in a public announcement request addressed “from No.113” wishing him happy birthday and stating “May the sun shine on you today and every day.” When No.2 learns that No.113 is deceased, he suspects the man who read the announcement – the Supervisor (Peter Swanwick) – and has him sacked, too. No.6 even delivers a cuckoo clock to No.2’s doorstep, and a bomb squad called; it turns out to be nothing more than a cuckoo clock. A carrier pigeon No.6 sends is intercepted, and the message it carries is the “Patty Cake” nursery rhyme. When even No.14 is fired under the growing paranoia of No.2, he confronts No.6 in his house. They fight, and No.6 throws No.14 through the window. At last No.6 visits No.2 again in the Green Dome, but by now No.2, who has even fired the Butler, has reached a nervous breakdown. He totally believes that No.6 is a plant sent to report on him, and No.6 tells him that if this were true, he should never have interfered with the operation. He convinces No.2 to phone No.1 and resign.

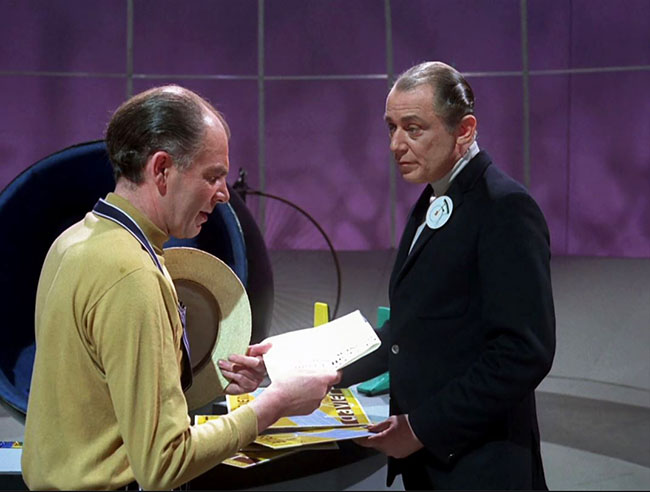

No.2 (Patrick Cargill) receives a report from the Shop Assistant (Victor Woolf).

OBSERVATIONS

“Hammer Into Anvil” represents the best of the “realistic” episodes of The Prisoner (as opposed to the more surreal outings). This is a fantastic episode, demonstrating how a powerless prisoner can dominate his environment through psychology, inverting the balance of power so that the warden becomes the prisoner. It’s the only Prisoner script by Roger Woddis, who didn’t write much TV but was an accomplished poet and dramatist, possessing a satirical bent and politically outspoken (he was a member of Great Britain’s Communist Party). It’s a showcase for Patrick Cargill, who appeared in an earlier episode, “Many Happy Returns,” as one of No.6’s colleagues, Thorpe. Shortly after The Prisoner he would go on to play the lead in the long-running ITV series Father, Dear Father. I mentioned in my review of “Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling” that a stronger idea for a stand-alone, non-McGoohan episode would be to spend the hour focusing on No.2. It wasn’t until rewatching “Hammer Into Anvil” that I realized this is pretty much just that: No.2 is the main character here, not No.6. Which is perfect, because No.2 is the one being tormented in this episode, and No.6 the authority figure, even if it’s a sustained act of illusion. Despite the very successful humor, this is a rather dark episode. It begins, after all, with a woman – who’s attempted suicide before – now driven to jump to her death by No.2. (Pretty shocking for a TV show in 1967.) Recall that in “Arrival” No.6’s colleague Cobb was said to have leaped from a Hospital window too, a lie to manipulate No.6. Here is the terrible true version, and it drives No.6 into his scheme for the sake of revenge.

Hilary Heath as the tragic No.73.

Cargill’s arc begins as a confident “professional sadist,” as No.6 characterizes him, but he plummets into endless suspicion, firing even the stalwart cast regulars Peter Swanwick and Angelo Muscat, and bottoms out a cringing basketcase before the triumphant No.6. “You didn’t fool me!” No.2 declares in his final moment of hysteria, accusing No.6 of being sent to spy on him. No.6 cleverly responds, “Maybe you fooled yourself?” No.2 requires only the slightest nudge to believe that he could be considered treasonous to the Village, and that his own chance lies in leaving his position. The episode ends on a remarkable moment for Cargill as he gathers himself together, steadies his voice, and says into the phone, “I have to report a breakdown in control. No.2 needs to be replaced. Yes, this is No.2 reporting.” He then collapses into his globe chair, curling into a fetal position, completely conquered while he listens to the unheard authority on the other end of the line. Throughout the episode, only No.14 sees through No.6, telling No.2, “He’s out to poison the whole Village.” But the poison proves irresistible to No.2, and he voluntarily begins dismantling the Village bureaucracy as though following No.6’s every desire. Indeed, No.2 has acted as a saboteur, just as No.6 accuses him.

Refreshingly, “Hammer Into Anvil” features extensive Portmeirion location shooting, blended more seamlessly with the MGM sets than, say, “A Change of Mind.” We get to spend some time in such familiar locations as the Stone Boat and the Village bandstand. We also watch a quick match of kosho (for the second and last time), and pay another visit to the Village General Store, which is now tended by a different Villager than Denis Shaw’s shopkeeper from “Arrival” and “Checkmate.” (This makes sense, seeing as the shopkeeper volunteered for No.6’s escape plan in “Checkmate.” He was probably sent to the Hospital as punishment.)

The Supervisor (Peter Swanwick) has his observers keep a close eye on the Prisoner.

SEQUENCE

My placement of the episode this late in the series owes a debt to the 1987 Six of One publication Village World. In a letter to the author/editor Max Hora expressing his own opinions on the episode order, Trevor L. Ruppe of North Carolina wrote, “No.6 is the most confident of himself here and [“Hammer Into Anvil”] should go nearest the end. This story sees him at his most ruthlessly violent, doing everything he can to break No.2. The Village now realizes that the most drastic measures must be taken…” Although Mr. Ruppe is not the only fan to have come to that conclusion, I quote him here because I’ve been influenced by his letter ever since I picked up a copy of Village World at the Portmeirion Prisoner Shop in the mid-90’s. Ruppe has “Hammer Into Anvil” going straight into “Once Upon a Time,” which makes complete sense, and I preferred sequencing those two episodes as such for a very long time. But I’m going to slot “The Girl Who Was Death” in next instead, for reasons I’ll explain next time.

Still, as Ruppe notes, we can see that the No.6 of this episode is so indomitable that the Village authorities must do something about him once and for all. In “A Change of Mind” he runs No.2 out of the Village with a mob. Now he has manipulated the new No.2 into destroying himself. These must be treated as very late episodes in the series, as they help explain why the Village resorts to the process called “Degree Absolute.”

No.14 (Basil Hoskins) fights No.6 in a game of kosho.

FISTICUFFS

Again, the traditional Prisoner fight scene is used to liven up an episode that’s focused on mind games: No.6 refuses to see No.2, and so the usual thugs in striped shirts take him down. Later a game of kosho provides additional action as No.14 makes it personal.

PROPAGANDA

Signs hung in the General Store guarantee than in The Prisoner even buying a record can seem like an act of Orwellian conformity: “Music Makes a Quiet Mind.” “Music Begins Where Words Leave Off.” “Music Says All.” The joke here is that No.2 desperately tries to read into No.6’s obsession with finding the right Bizet record from a number of identical copies, but No.6’s eccentric activity is actually saying nothing.

METHODOLOGY

No.2 is not the one with a methodology here; it is No.6, who drives No.2 to the brink of insanity by drawing from his years of experience in the intelligence field.

WIN OR LOSE?

Inarguably, a win.

QUOTES

No.2: I want to talk about you.

No.6: You’re wasting your time. Many have tried.

No.2: Amateurs.

No.6: You’re a professional. A professional sadist?No.2: Each many has his breaking point, you know. And you are no exception.

No.2: Du musst Ambose oder Hammer sein.

No.6: You must be anvil or hammer?

No.2: I see you know your Goethe.

No.6: And you see me as the anvil?

No.2: Precisely. I’m going to hammer you.No.6: You could be working for the enemy. Or you could be a blunderer who’s lost his head. Either way you’ve failed. And they do not like failures here.

No.2: You’ve destroyed me.

No.6: No. You destroyed yourself.

UP NEXT: THE GIRL WHO WAS DEATH