Deep in the Arctic wilderness of Lapland, the young Sámi woman Pirita (Mirjami Kuosmanen), newly married to the kind but intimately remote reindeer herder Aslak (Kalervo Nissilä), takes drastic measures to relieve her sexual frustration. During one of her husband’s many extended absences, Pirita visits the shaman Tsalkku-Nilla (Arvo Lehesmaa), who initiates her into an occult rite that promises no man will be able to resist her, should she only sacrifice the first living creature she encounters on her return journey. That creature is a young white reindeer, which she carries off to an eerie antlered altar in the center of a reindeer graveyard carpeted with snowdrifts. Then – all is well, until she finds herself frequently wandering the wilds in a state of constant metamorphosis: prancing white reindeer with long antlers; Pirita, liberated and feral; Pirita, vampire-fanged. The hunters who pursue the white reindeer are dazzled by her sudden transformation, then destroyed by her. Rumors of a witch in the shape of a reindeer spread in the scattered snowy shelters and around those huddled over fires – wives warn their husbands not to chase the reindeer into Evil Valley, from which none ever return alive. And Aslak forges a spear and sets his mind on hunting the reindeer, while Pirita looks on in fear, her splintering identity compelling her back through the white hills.

Reindeer herding.

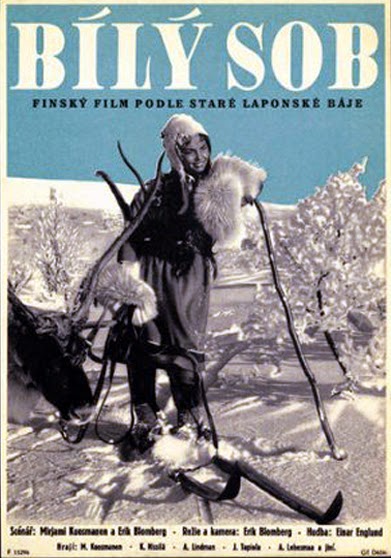

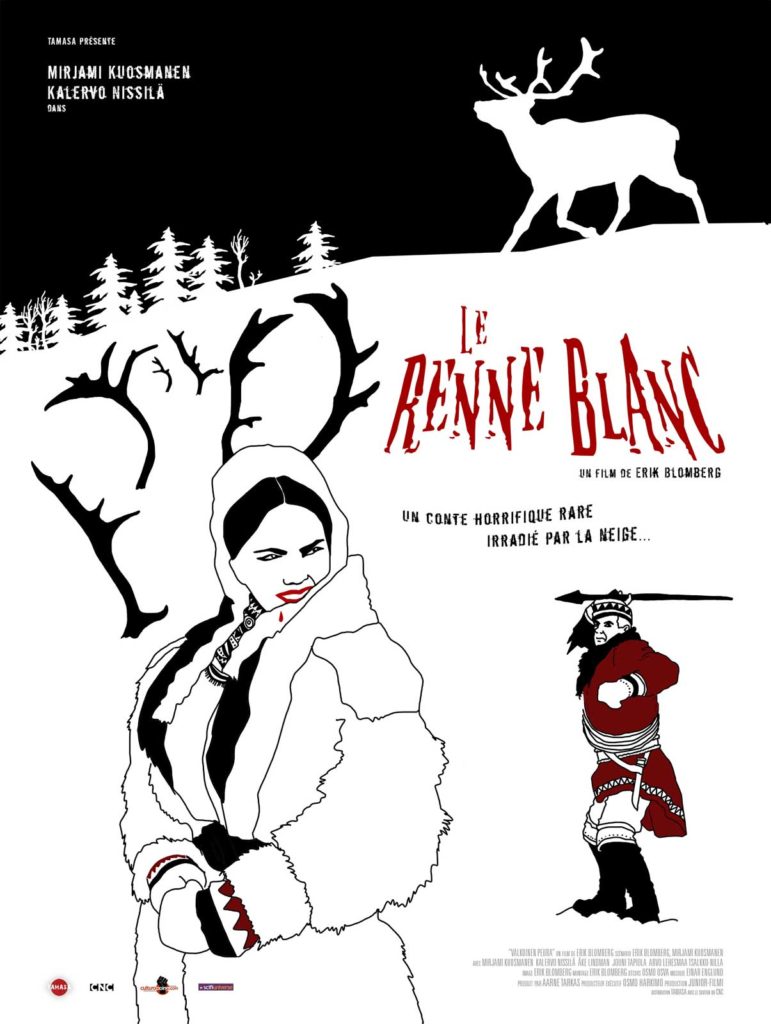

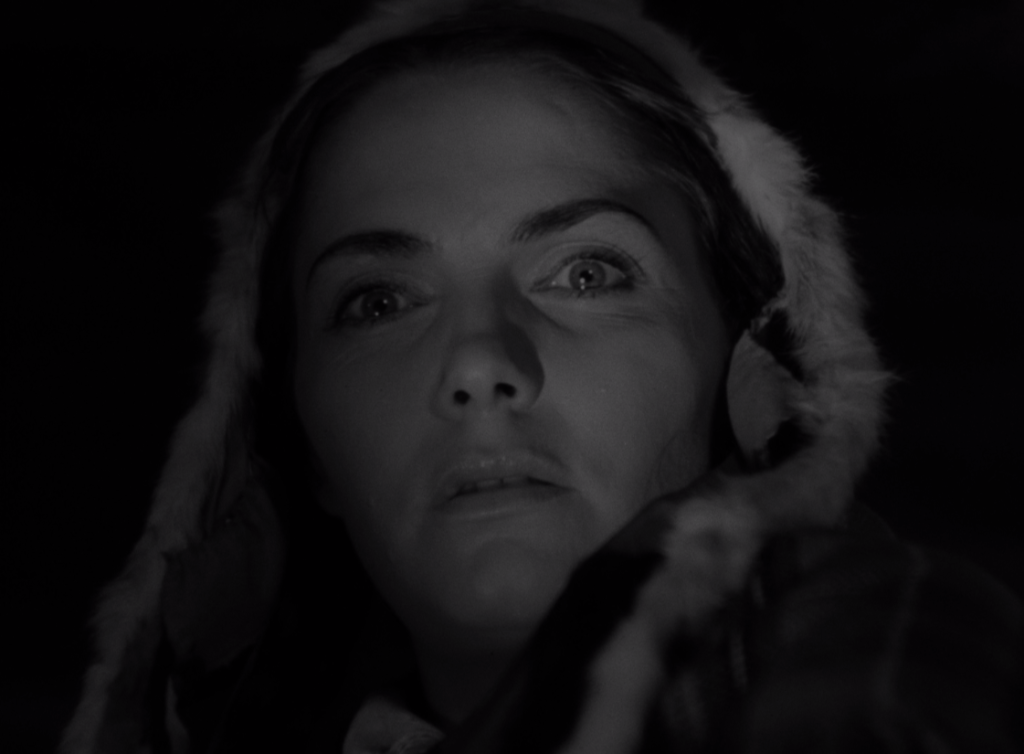

The White Reindeer (Valkoinen peura, 1952), often classified by genre enthusiasts as an unusual twist on the vampire tale, was long available only through bootlegs and torrents before finally, in 2019, joining the Masters of Cinema line from Eureka! in the UK as a Blu-ray/DVD package. Produced from a 2016 4K restoration by the National Audiovisual Institute of Finland, the film can now be appreciated for both its incredible beauty – directed by Finnish documentarian and cinematographer Erik Blomberg (the star’s husband) – and the fact that it’s much more of a dark, primal fairy tale than something as narrowly defined as a vampire picture. Pirita is a witch – deep down, even before she makes her fateful decision that puts her body in flux. It’s something that’s recognized by the shaman, as his secret ceremony to cast his spell is unexpectedly co-opted by Pirita and the wild spirit that’s been shackled inside her. She takes charge of her own transformation, and the shaman is shunted to the side. What he only provides, perhaps, is the key to unlocking what she already had. Once she sacrifices the white reindeer, she becomes the creature that the men of her village herd over the horizon and wrestle violently by the antlers. The first hunter to encounter her chases her down trying to rope her, but when he seizes her antlers and twists her neck against the ground, she is suddenly Pirita, standing tall in the center of Evil Valley and grinning with a boldness that’s different than all her warm smiles in the film’s first act. Kuosmanen’s performance dominates the film – she effortlessly tracks Pirita’s evolution from a smitten and shy young woman to a confident, sexual creature, as well as the guilt, confusion, and hunted terror required as the plot advances toward its foregone conclusion.

Mirjami Kuosmanen

Blomberg’s style is captivating, with one foot in fantastic cinema and another in Robert Flaherty’s pseudo-documentaries about communities surviving in harsh conditions. One could easily enjoy the film without the fantastic elements; it’s dazzling enough watching hundreds of reindeer being herded through the hills, or a careening reindeer-driven sled race. These are the true special effects in the film. When Pirita shapeshifts, Blomberg simply cuts from reindeer to Pirita to exposed fangs. Similarly, whatever she actually does to her victims is never depicted. When one body is retrieved and inspected, we only see the horrified expressions of the community, as well as Pirita’s turning away in quiet revulsion. Blomberg also treats close-ups with the striking, isolated portraiture style of Carl Dreyer. The combined effect is that of viewing an ancient, vital piece of folklore as it might have actually happened, an aberration from reality in a landscape so naturally surreal that it’s possible to believe that spirits and witches might dwell in snowy burrows or outside the flap of the tent while everyone stacks atop each other intimately for body heat. In such a scene, we see Pirita clumped together among the bodies, looking completely alone. No wonder she escapes that false sense of comfort to hop through the snows and taste the crisp icy air as the white reindeer.