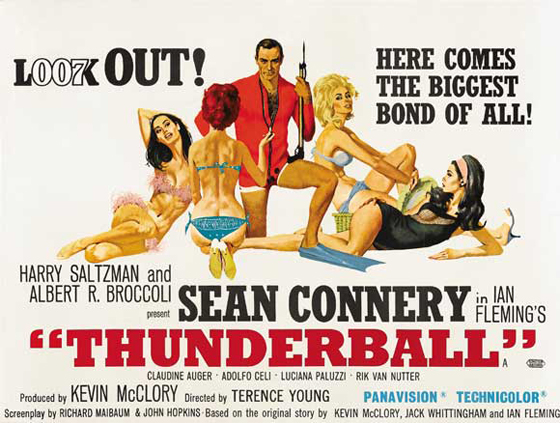

In a way, things had changed. Although Bond was getting bigger all the time, and Thunderball (1965) was the natural evolution, there passed a point where the films were not merely high-profile adaptations of Ian Fleming bestsellers. The series was now a brand, so appealing in the formula that copycats and parodies emerged from all sides. What those imitations could not match was the execution: the style, the quality, the sly humor, the scale. As I’ve been working my way through the films for the umpteenth time (in case you’re wondering why I skipped ahead from Dr. No, my reviews of From Russia with Love and Goldfinger were posted last year), it really strikes me that it’s Thunderball, not George Lazenby, that marked Chapter Two for the Bond series. Consider that you don’t really need more than the first three James Bond films. (Bear with me.) Dr. No (1962) established the character and the key concepts: exotic location, girls, supervillain. From Russia with Love (1963) was a classic espionage tale, improving upon its predecessor in every way, and truly bringing Ian Fleming’s writing to celluloid; it also presented the idea of a title song (never mind that it isn’t sung over the opening titles – they’d fix that). With Goldfinger (1964) introducing a new director, Guy Hamilton, the series began to take itself a little less seriously, sacrificing logic for sheer entertainment. It gave us the classic Bond theme song courtesy Shirley Bassey, Pussy Galore and her judo, and Goldfinger and his laser beam; it reveled in Q’s gadgets, including the iconic Aston Martin DB-5. All of this still felt fresh. Just as it took the recent Daniel Craig reboot a full three films to bring all of its classic elements together, this too is how it all began. With Thunderball, then, Harry Saltzman and Albert R. Broccoli faced the conundrum of what to do next. They risked repeating themselves, and, in truth, they did. That’s the trouble with a successful formula: you have to stick to it or risk losing your audience. More than that, you have to top yourself each time out. Thunderball‘s budget was three times that of its predecessor’s. Goldfinger‘s climax featured a big-scale battle at Fort Knox, so Thunderball‘s equivalent takes place entirely underwater, with the soldiers all in diving suits. The posters proudly declared this was “The Biggest Bond of All!”

On set, Luciana Paluzzi and Sean Connery pose for the cameras.

If Saltzman and Broccoli had their druthers, Thunderball would have been the first 007 film, and it’s easy to see that its prototypical story would have made a fine introduction to the character and his world: the terrorist organization SPECTRE steals two atomic bombs, hiding them in the Bahamas and holding them for ransom, with Bond racing to find the weapons before one can be detonated. It’s a fine fit for an action film because that’s what it was originally intended to be: Fleming’s 1961 novel was based upon a screenplay written years earlier, called Longitude 78 West, that he had drafted with filmmaker Kevin McClory (The Boy and the Bridge), screenwriter Jack Whittingham (who would go on to write for the Danger Man TV series), and Fleming’s friends Ivar Bryce and Ernest Cuneo. McClory was set to produce the film, but after the project fell apart, Fleming went ahead and wrote Thunderball based on the unfilmed script without McClory’s blessing and without proper credit. McClory and Whittingham sued, and with the case pending, Saltzman and Broccoli’s EON Productions – succeeding where McClory failed by finally bringing Bond to the big screen – made the wise decision to skip over the bestseller and its ugly legal entanglements, and adapt other Bond novels instead. But once the case was resolved (Fleming losing big: paying hefty damages and surrendering all future Thunderball film rights to McClory), EON was now faced with a potential rival Bond project. According to a recent article on the 007 website MI6:

Whilst Goldfinger was in production, Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman decided that On Her Majesty’s Secret Service would be the fourth film in the series, to be released in 1965. In September 1964, Kevin McClory approached Broccoli and Saltzman with an offer to co-produce a big screen adaptation of Thunderball (the only novel, along with Casino Royale, that EON Productions could not adapt at that time). Rather than risk a rival production hitting screens just as they were about to experience the peak of their achievements, EON decided to collaborate with McClory and make Thunderball next. They would make McClory producer and give him 20% of the film’s profits.

Adolfo Celi as Emilio Largo, SPECTRE's Number Two.

One of the most frustrating aspects of this turn of events is that so many of us would have loved to have seen a Connery version of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, one of Fleming’s best Bond novels. If Thunderball is the first Bond film in which the series begins to repeat itself – or, pardon the expression, starts to tread water – that would not have been an issue if Eon had made OHMSS instead: a story in which Bond suffers a great tragedy that will further define his character. (As it is, the Lazenby-led 1969 version remains one of the best-crafted films in the series.) What we get is a film made out of necessity, and not as remarkable or as significant as what came before – and that, in itself, is significant, because the series has a longevity that requires solid and “routine” Bond films. That’s what Thunderball is, and there’s no crime in it. Bond fans value the film today for a few reasons, not the least of which is that Connery only made a limited number of these, and in Thunderball he still retained some of his impish charm on-screen; he wasn’t quite exhausted of the role just yet. And we do get a handful of iconic moments that bring great pleasure on every viewing. There is, for example, that scene which introduces Emilio Largo (Adolfo Celi, Von Ryan’s Express), which broadens our understanding of SPECTRE’s scope. The organization, first referenced back in Dr. No (the film, at least), seems more dangerously anarchic than before, as their plot involves not just extortion but also the detonation of nuclear weapons. In another fantastic Ken Adam set, we see their secret conference room, where Blofeld – “Number One” – can wantonly execute any of his seated subordinates with the press of a button; he hardly needs to stop petting his cat. (One thing I love about Blofeld: he sure does like killing the person standing next to you just to teach you a lesson.)

In the pre-credits scene, Bond makes his escape using a (real) jetpack.

The budget was now so large that whatever Adam drew, they built. Largo’s Nassau estate, perched attractively on the coastline, has a pool filled with sharks. His yacht, the Disco Volante, can split in two, a rocketing speedboat breaking free of a shell that can be used as a floating fortress. Largo’s men travel to and from a submerged Vulcan bomber plane using sleek submersibles. Even 007’s island hotel suite looks bigger than my house. It was necessary for all Bond copycats to pale by comparison, and they did; Thunderball was intended to be a blockbuster. The pre-titles sequence, a tradition first established in From Russia with Love, reached new heights, literally, as Bond tries on the latest from Q Branch, a jetpack, to escape from enemy agents in Paris; Bond was now a pulp hero to match the likes of Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon. (This particular gadget, developed by Bell Aircraft, was very real and very functional, though one wonders, even after the demonstration, why a spy would ever need one in the field.) There’s a nice sense of continuity in these early Connery films, broken only by the changing face of Felix Leiter (here, he’s played by Rik Van Nutter, the series’ third Felix): Bond squeeze Sylvia Trench appeared in both Dr. No and From Russia with Love, and the Aston Martin DB5 now makes its second appearance after Goldfinger. But Bond only gets to use a couple of its gadgets – raising a bulletproof shield, and blasting his pedestrian pursuers with streams of high-powered water. Later, he’ll pop open the car’s control panel, offering an appetizing glimpse of its many deadly weapons, but the opportunity to use them will be stolen by an equally deadly rival – the fabulous Fiona Volpe (Luciana Paluzzi).

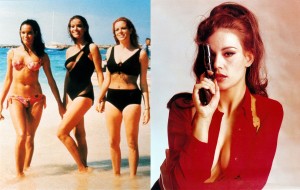

A trio of memorable Bond girls: (L) Martine Beswick, Claudine Auger, and Luciana Paluzzi; (R) Auger poses as Domino.

Voluptuous Volpe is my favorite of the series’ many femme fatales. As one of SPECTRE’s most effective agents, she drives a motorcycle that fires rockets, and drives so fast and recklessly that even Bond, as her passenger, becomes visibly nervous. She storms Bond’s suite by kidnapping his fellow agent Paula (Martine Beswick, formerly a gypsy girl in From Russia with Love), and then slips naked into the tub to await his arrival. This leads to one of the sexiest, and funniest, seduction scenes in the series: Bond’s answer to “Would you mind giving me something to put on?” is to hand her a pair of slippers. But Fiona deliberately separates herself from Pussy Galore, to whom there’s a subtle reference when she gives Bond a post-coital dressing-down: “I forgot your ego, Mr. Bond. James Bond, [who] has to make love to a woman, and she starts to hear heavenly choirs singing. She repents, and turns to the side of right and virtue. But not this one!” Paluzzi has an appealing Catwoman purr of a voice, and she gets to keep it, a rare privilege in these early Bond films. Ex-Miss France Claudine Auger, on the other hand, suffers the indignity of being dubbed with what might be called “European voice.” In other words, she sounds just like dubbed women of Bond films past. (Not surprising, since the woman who voiced her, Nikki van der Zyl, also spoke for Ursula Andress in Dr. No.) Neither is Auger, as Dominique “Domino” Derval, given as interesting a character to play: a step down from the women in Goldfinger, she’s less forthright, more the damsel-in-distress (barring the climactic moment when she finally takes her revenge). Over a long acting career, Auger would prove that she had more to offer than just good looks, though – on those latter points – it should be noted that she is one of the most breathtakingly beautiful women of the entire Bond series. Apart from Paluzzi, Auger, and Beswick (talk about a cult figure – she’d soon be a “Hammer Glamour” girl), Molly Peters, a pin-up from various men’s magazines, is given some fairly risqué material in early scenes as Bond’s physical therapist. Her appearance is only tainted by Connery-era sexism; a scene in which he blackmails her resistant character into sex is bound to leave a sour taste for the modern viewer.

Lobby card: Bond faces Fiona Volpe and her henchmen.

Terence Young, veteran of the first two Bond films, returned to direct when Guy Hamilton turned down the project. Young’s touch is unmistakable – pulp spectacle treated with cool and elegance – but the film feels oddly lethargic compared to its predecessors. As much as I enjoy Thunderball, there are parts that always seem like a chore. Key scenes just go on for too long, such as the stealing of the Vulcan bomber and nearly all of the underwater sequences. Mind you, that footage – in particular the final battle with dozens of divers in combat – is technically impressive, but it requires a merciless trim. At 130 minutes, and without enough narrative incident to justify the running time, Thunderball marks the moment when the Bond series had finally begun to bloat. The theme song is, perhaps inevitably, a step down from Shirley Bassey, with Tom Jones crooning some silliness about striking “like Thun-der-baaaaall!” At least two stabs at a title song were made before this third, adequate attempt was settled upon, but I would have preferred they retained the second, “Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang” (a reference to what the Japanese – one of Bond’s biggest fan bases – called 007). Both Bassey and Dionne Warwick recorded takes of the song, but it survives in the finished film only in John Barry’s score, an instrumental version utilized frequently and effectively to offer some welcome, loungey swing to the occasionally slow-moving proceedings. With Thunderball, Barry also continued to push his alternate, bombastic theme to Mr. Bond, called simply “007,” but it just can’t approach the original “James Bond Theme” by Monty Norman. After a while, he’d give it up.

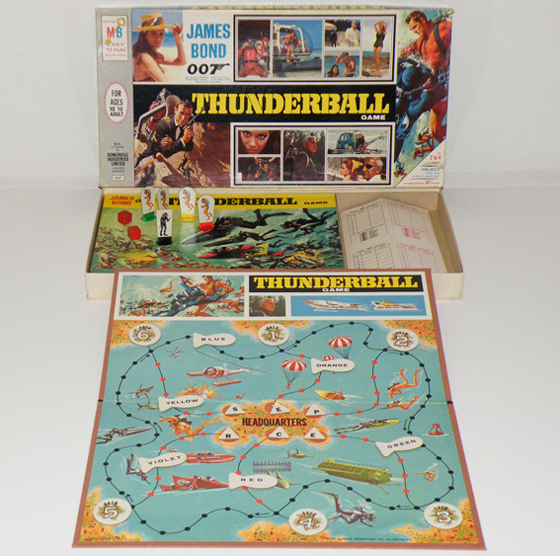

The Thunderball board game.

The film was the biggest Bond hit yet, breaking box office records. The film was marketed with numerous Thunderball toys, including scuba-diving action figures, a toy speedboat, a snorkel, and a Milton Bradley board game. There was no turning back, at least not for now: Fleming’s original creation would begin to recede as the phenomenon that was the James Bond brand skyrocketed. (Connery, weary of the attention, only gave one interview, and otherwise hid from the press. His relationship with the franchise would be rocky from this point forward.) Ironically, to a modern viewer, Thunderball seems less like a “blockbuster” as we know the term now; the film is casually paced, relying mainly on Connery’s charm, sexy women, and beautiful location shooting. It works best with modest expectations: enjoy it as a vicarious weekend getaway in the Bahamas with 007. Despite his temporary partnership with Saltzman & Broccoli, McClory wasn’t done with Bond, resurfacing not just with his Thunderball rights but with Connery himself in 1983’s unsatisfactory Never Say Never Again. The film would be pitted against EON’s Octopussy that year, with Roger Moore beating Connery at the box office. McClory, who passed away in 2006, would periodically threaten another Thunderball remake, and it was not until November 15th of this year that MGM announced the acquisition of McClory’s interests in all things Thunderball, finally placing all James Bond cinematic licenses under one banner. Whether this means the return of SPECTRE and/or Ernst Stavro Blofeld to the Bond series is an open question for now, but it certainly closes the chapter on one of the most problematic strains of the agent’s career on the big screen. I hope it means a remake of OHMSS – but I don’t think we need a third Thunderball.