2021 is the 10th anniversary of Midnight Only. To mark the occasion, this imaginary, rat-infested, leaky-roofed theater is raising the curtain on historically important midnight movies.

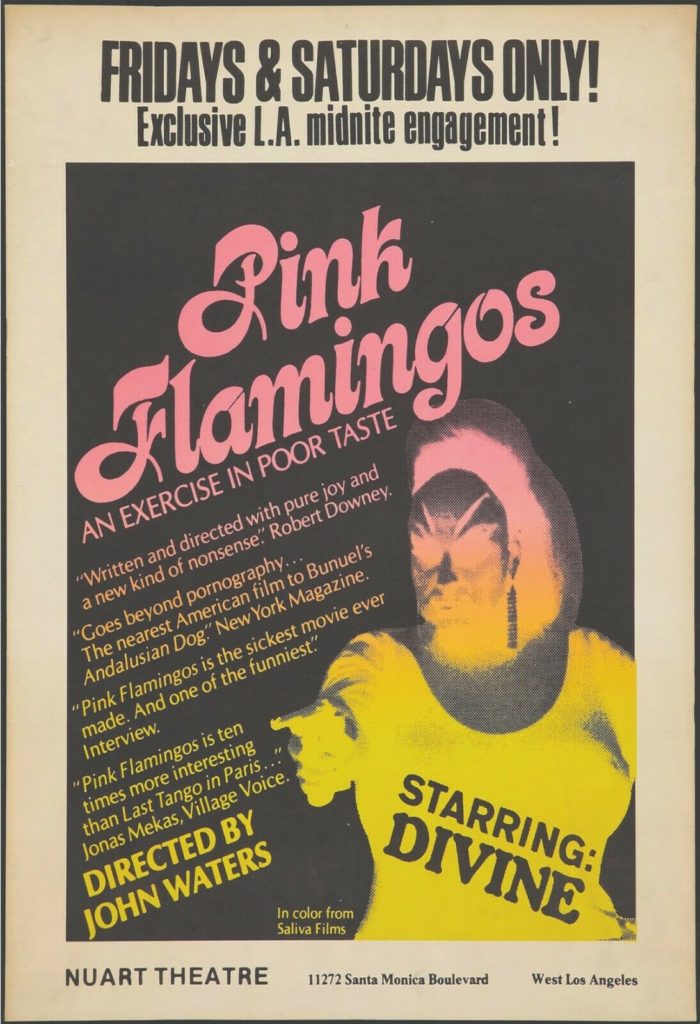

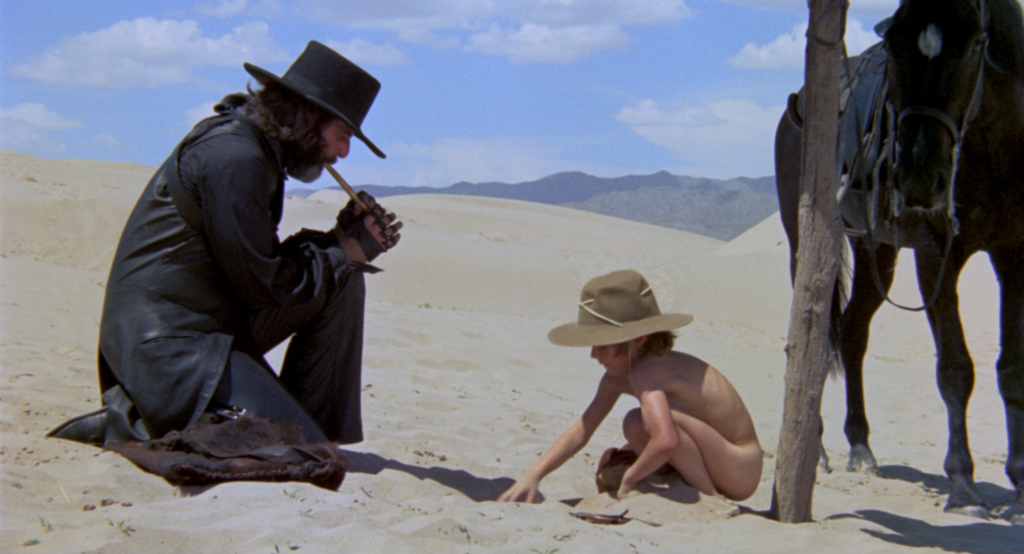

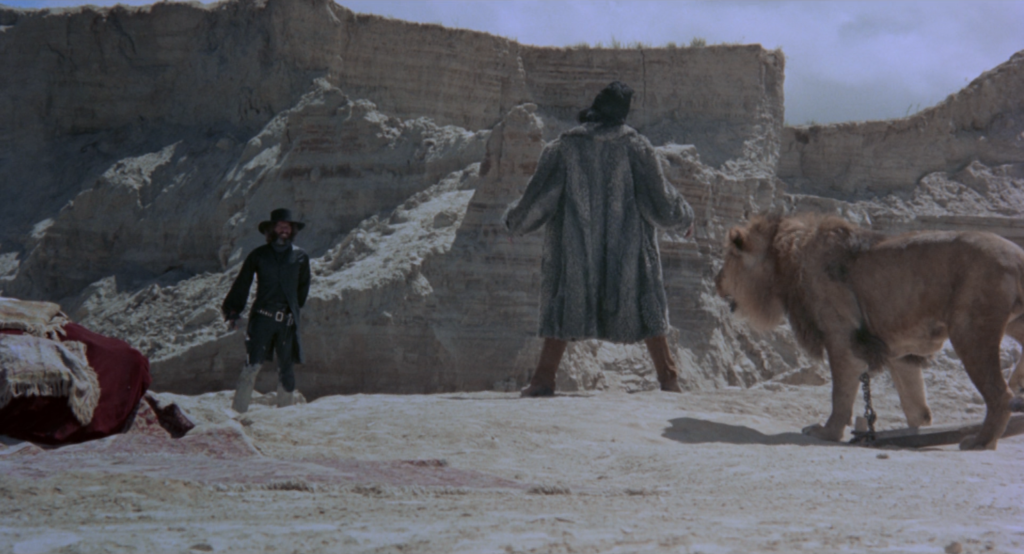

A key element in midnight movies is the act of transgression, a communal act of viewing forbidden images not fit for those now sleeping comfortably in their homes. Midnight movies grew directly out of the 60’s underground film screenings in New York City, in which no subject matter was off-limits, and the outlaws, the exiles, were celebrated. John Waters was a part of that evolving scene, and he wanted to make a midnight movie. He envisioned his diverse, adventurous, bizarrely costumed assemblage of friends and collaborators, his Baltimore-based “Dreamlanders,” performing in scratched-up 16mm before the rowdy crowds that embraced films like El Topo (1970) and Freaks (1932). His meal ticket, in this respect, would be Divine (real name: Glenn Milstead), Dreamland’s drag queen with makeup that appeared to have been conceived by an extraterrestrial gathering rough impressions of humankind from Lana Turner and El Santo. After two feature length films, Mondo Trasho (1969) and Multiple Maniacs (1970), the latter featuring Divine being raped by an enormous lobster (and now featured in the Criterion Collection), Waters pushed himself and his adventurous cast to new extremes with Pink Flamingos (1972), which included sights which had never before been committed to celluloid. This “exercise in poor taste” – an understatement – seduced nascent New Line Cinema, who agreed to distribute the film along the midnight movies circuit. It became an instant cult hit, running for ten years straight at LA’s Nuart Theatre. The trailer, which tantalizingly features no footage from the film itself, is an early example of the “audience reaction trailer” and offers a glimpse of those who were drawn to this forbidden artifact: gay, straight, students, couples – all are bowled over by what they’ve just seen. “Rex Reed told us that it’s fabulous,” says one woman. When asked why someone should go see a movie at midnight, she says, “Why go home at midnight? What are you going to see there?” Well, probably not a man with an asshole that lip syncs to “Surfin’ Bird.”

Mary Vivian Pearce and Divine gather beside Edith Massey’s crib.

If Waters makes filth more palatable, there is no greater test of this talent than Pink Flamingos, a film that crosses boundaries with flying leaps, not just to break taboos but to demonstrate a prodigious imagination for filth. If you are unprepared for Pink Flamingos, you will see things you probably don’t want to see, but also – and here’s the selling point – have never realized that you don’t want to see. Throughout, and even at its most vile, it is very funny. It is one thing to have corpulent, negligéed, snaggle-toothed Edith Massey sitting in a baby crib, her breasts smeared with eggs, demanding “Eggs! Eggs! Eggs!” This, by itself, is unsettling. But Waters has her trailer-living companions, including daughter Divine aka Babs Johnson, son Crackers (Danny Mills), and Cotton (Mary Vivian Pearce), patiently indulge her interest in eggs, and for the “Egg Man” (Paul Swift), an egg salesman, show up cribside to open a suitcase with eggs of different sizes in a velvet display, delivering my favorite line in the film: “What’ll it be for the lady who the eggs like the most?” The fact that the movie is frequently, gleefully disgusting is lightened by the self-parodying plot, in which Divine’s title of “The Filthiest Person Alive” (declared by the tabloid newspaper Midnight) is coveted by Connie and Raymond Marble (Mink Stole and David Lochary). The Marbles have been working overtime to be the filthiest people in Phoenix, Maryland. “As you know,” Connie Marble says, “we run a baby ring.” They kidnap hitchhikers, lock them in their cellar, dope them up, rape them, and turn their babies over “to lesbian couples.” They’re also toe-sucking foot fetishists, and Raymond has a part-time job flashing people in the park.

The press gathers for a trial and execution conducted by Divine and her clan.

Because this is a John Waters film, every line is delivered with exclamation points in the manner of a Russ Meyer picture or a Kuchar brothers camp melodrama. The soundtrack is an irresistible collection of (unlicensed, at the time) songs from his personal record collection, including Little Richard delivering the title track of The Girl Can’t Help It (1956) with Divine standing in for Jayne Mansfield, Waters’ camera tracking from a car window and capturing all the gawking, very real bystanders as this monument to punk glamor struts by. But this is not Hairspray (1988), or even Polyester (1981), which are cuddly by this standard. Our characters are quite serious about claiming that title of the filthiest people alive. In one scene, the chicken-obsessed Crackers fucks a spy for the Marbles, Cookie (Cookie Mueller), while shoving a live chicken between their naked bodies until they’re smeared with its blood. We’re offered up masturbation, an unsimulated, incestuous blowjob, extensive furniture licking, people being shot in the face, and cannibalism. Most famously at all – so not really a spoiler warning, but perhaps just a warning – the film ends where it can no longer proceed: while a breathless Waters narrates that what you are about to see is real, Divine stoops over behind a dog and eats its fresh shit. And gags. And grins at the camera.

Divine’s trailer.

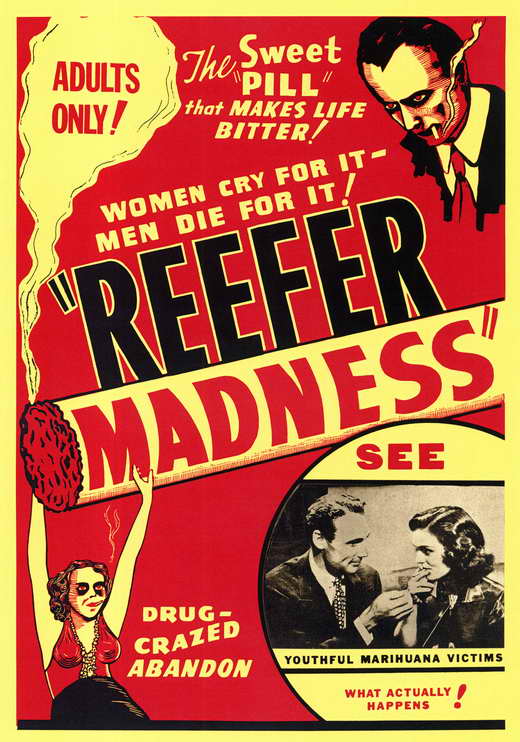

Appropriate then that the trailer for Pink Flamingos contains a critic’s quote comparing the film to Buñuel and Dalí’s eye-slicing short Un Chien Andalou (1929). This is what Surrealism intended: sheer provocation for its own sake, a bomb hurled at bourgeois complacency (or, in this case, straight-laced mainstream America). Waters wanted to provide a shock to the system, although for all the gritty, grimy, unfaked moments presented with ringmaster showmanship beside the faked ones, the film might as well be science fiction. Divine’s clan, along with blue-haired (and -pubed) Raymond Marble, bespectacled child peddler Connie Marble, and their rapist cross-dressing servant (Channing Wilroy), are cartoons who inhabit an absurd universe. (“The couch – it rejected you!” Connie Marble declares, right after we’ve seen a couch do just that to Raymond.) As Waters’ career moved forward, he leaned harder into this style and less on the Mondo approach. But in 1972, Deep Throat launched “porno chic,” mainstream films became edgier, and it was all the rage to make a trip to a downtown theater – perhaps a very disreputable one – to see the outrageously uncensored. It was a year made for Pink Flamingos.