When I was a teenager, I thought Clive Barker was the bee’s knees. The blood-spattered bee’s bloody, bloody knees. I first encountered him through Weaveworld, which I’d expected to be a sex-and-violence fantasy novel; instead I was initiated into the genre of urban fantasy – with Goth sensibilities, a gritty environment, eroticism, wit, and a mythology complex and varied enough to comfortably contain witches, shapeshifters, and an exiled angel from the Garden of Eden. So I was hooked, and began to consume all his novels, including his volumes of short stories, The Books of Blood, his children’s book The Thief of Always, and the comic books inspired by his books and films. It seemed to take a while before I reached his most famous work, the low-budget horror film Hellraiser (1987), which he wrote and directed. I stepped backward toward it slowly, perhaps with trepidation. I seem to recall reading The Hellbound Heart, the novella which inspired it, first. (My mother worked at an independent bookstore, and I asked her to special order it for me. She brought it home, showed me the cover image of a cross-legged man without any skin, and said, “You’re reading this?”) But, as a Barker fan, I was both surprised and satisfied by the film. I was expecting it to be a gruesome and over-the-top splatter picture – and it is, of course – but it was also faithful to Barker’s book, true to his philosophies, and, like so much of his fiction, a full-blooded, adult-oriented fairy tale.

When I was a teenager, I thought Clive Barker was the bee’s knees. The blood-spattered bee’s bloody, bloody knees. I first encountered him through Weaveworld, which I’d expected to be a sex-and-violence fantasy novel; instead I was initiated into the genre of urban fantasy – with Goth sensibilities, a gritty environment, eroticism, wit, and a mythology complex and varied enough to comfortably contain witches, shapeshifters, and an exiled angel from the Garden of Eden. So I was hooked, and began to consume all his novels, including his volumes of short stories, The Books of Blood, his children’s book The Thief of Always, and the comic books inspired by his books and films. It seemed to take a while before I reached his most famous work, the low-budget horror film Hellraiser (1987), which he wrote and directed. I stepped backward toward it slowly, perhaps with trepidation. I seem to recall reading The Hellbound Heart, the novella which inspired it, first. (My mother worked at an independent bookstore, and I asked her to special order it for me. She brought it home, showed me the cover image of a cross-legged man without any skin, and said, “You’re reading this?”) But, as a Barker fan, I was both surprised and satisfied by the film. I was expecting it to be a gruesome and over-the-top splatter picture – and it is, of course – but it was also faithful to Barker’s book, true to his philosophies, and, like so much of his fiction, a full-blooded, adult-oriented fairy tale.

Although he’s torn to bits about three minutes into the film, the central character in the story is Frank (performed by Sean Chapman, and then, under gooey oodles of makeup, Oliver Smith). Frank’s a nomadic pleasure seeker sifting through every culture and religion for the next transcendent sensation. In the film’s opening scene, he’s obtained the ultimate in decadent esoterica, a little puzzle box which is said to open doors to pleasures beyond pleasures. Actually, solving this particular Rubik’s Cube opens a portal to another dimension, out of which emerge the Cenobites, grotesque, leather-clad figures, with pierced and peeled-back flesh; they command hooked chains, which whip out of the darkness and promptly rip Frank into scattered jigsaw pieces…which one of the Cenobites then attempts to reassemble on the floor (one gets the feeling these demons are solving Will Shortz puzzles while fighting boredom in their extra-dimensional S&M dungeons). This is perhaps not the kind of pleasure that Frank was seeking, though the Cenobites seem to take a lot of pride in it.

Although he’s torn to bits about three minutes into the film, the central character in the story is Frank (performed by Sean Chapman, and then, under gooey oodles of makeup, Oliver Smith). Frank’s a nomadic pleasure seeker sifting through every culture and religion for the next transcendent sensation. In the film’s opening scene, he’s obtained the ultimate in decadent esoterica, a little puzzle box which is said to open doors to pleasures beyond pleasures. Actually, solving this particular Rubik’s Cube opens a portal to another dimension, out of which emerge the Cenobites, grotesque, leather-clad figures, with pierced and peeled-back flesh; they command hooked chains, which whip out of the darkness and promptly rip Frank into scattered jigsaw pieces…which one of the Cenobites then attempts to reassemble on the floor (one gets the feeling these demons are solving Will Shortz puzzles while fighting boredom in their extra-dimensional S&M dungeons). This is perhaps not the kind of pleasure that Frank was seeking, though the Cenobites seem to take a lot of pride in it.

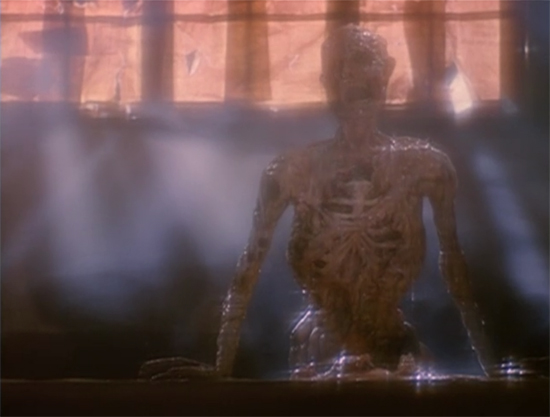

But we’re not done with Frank, because soon occupying his home are his squeamish brother Larry (Andrew Robinson) with his new wife Julia (Clare Higgins). They’re wondering where Frank went, but Julia will soon enough find out. After Larry cuts his hand on an exposed nail, dripping what seems like several gallons of blood on the floorboards of Frank’s abandoned room, the disassembled brother is revivified, though only about halfway. He greets Julia as a skeletal, slimy mess, begging her for more blood so that he can regain the rest of his tissues. (If not, I suppose he could go join one of those travelling Body Works exhibits.) Julia, who once had an affair with Frank, is eager to seek sexual satisfaction with him again – but this means letting him grow some skin first, so she’s driven to picking up men, bringing them back to Frank’s room, and smacking them on the head with a hammer, Maxwell-style. Frank subsequently gains more flesh and muscle, but both Larry and his grown daughter, Kirsty (Ashley Laurence), are beginning to catch on that something strange is happening inside the house. Eventually, Kirsty meets the hideous Frank, and steals the puzzle box from him when she learns it’s the one thing he fears. One night, while lying in a hospital bed following her unpleasant encounter with Frank, Kirsty begins to play with the box; and she finds out for herself just why her undead uncle is so terrified.

But we’re not done with Frank, because soon occupying his home are his squeamish brother Larry (Andrew Robinson) with his new wife Julia (Clare Higgins). They’re wondering where Frank went, but Julia will soon enough find out. After Larry cuts his hand on an exposed nail, dripping what seems like several gallons of blood on the floorboards of Frank’s abandoned room, the disassembled brother is revivified, though only about halfway. He greets Julia as a skeletal, slimy mess, begging her for more blood so that he can regain the rest of his tissues. (If not, I suppose he could go join one of those travelling Body Works exhibits.) Julia, who once had an affair with Frank, is eager to seek sexual satisfaction with him again – but this means letting him grow some skin first, so she’s driven to picking up men, bringing them back to Frank’s room, and smacking them on the head with a hammer, Maxwell-style. Frank subsequently gains more flesh and muscle, but both Larry and his grown daughter, Kirsty (Ashley Laurence), are beginning to catch on that something strange is happening inside the house. Eventually, Kirsty meets the hideous Frank, and steals the puzzle box from him when she learns it’s the one thing he fears. One night, while lying in a hospital bed following her unpleasant encounter with Frank, Kirsty begins to play with the box; and she finds out for herself just why her undead uncle is so terrified.

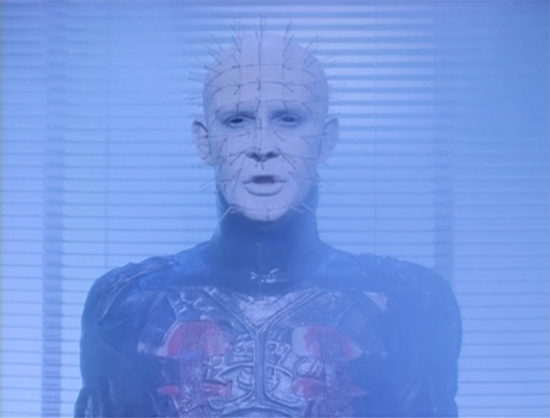

I wish this film existed in a vacuum, free from the overkill franchise which followed (sequels, comic books, toys). Barker, an author first and filmmaker second, nonetheless intuitively understands that a film must tell its story primarily with visuals. What impresses me most about the film now – revisiting it after many years – is that the elaborate mythology is only suggested, not told. Mostly, the viewer must imagine the world that the box opens, why the box exists in the first place, and who that mysterious man is who’s eating insects in Kirsty’s pet store (I like to think it’s the same sinister hobo from Mulholland Drive). It’s not the “Lament Configuration” – at least, I don’t think I heard those words spoken during the film. It’s just a little, mysterious cube. Frank calls these creatures the Cenobites, but that’s about all we know; Pinhead is not Pinhead, but “Lead Cenobite” (the fans thought “Pinhead” was a better name, and so it stuck). Doug Bradley, who would reprise the role over the many sequels and became a popular horror icon, gets just a few lines, and in one of them he suggests that they might be demons, and thus they might be from Hell. But the viewer can still suss out that the more likely explanation is that they are creatures who inspired our notion of demons, from a world that inspired the notion of Hell. Clive Barker leaves it to the viewer, and that’s perfect, but it’s evocative enough. The comic books and the fan fiction could have chugged along just fine without sequels that exhaustively explain everything from who built the Lament Configuration to who Pinhead really is. (Still, it is nice to have a horror franchise built around an elaborate, Lovecraftian mythology, rather than the more mind-numbing slasher film model.)

I wish this film existed in a vacuum, free from the overkill franchise which followed (sequels, comic books, toys). Barker, an author first and filmmaker second, nonetheless intuitively understands that a film must tell its story primarily with visuals. What impresses me most about the film now – revisiting it after many years – is that the elaborate mythology is only suggested, not told. Mostly, the viewer must imagine the world that the box opens, why the box exists in the first place, and who that mysterious man is who’s eating insects in Kirsty’s pet store (I like to think it’s the same sinister hobo from Mulholland Drive). It’s not the “Lament Configuration” – at least, I don’t think I heard those words spoken during the film. It’s just a little, mysterious cube. Frank calls these creatures the Cenobites, but that’s about all we know; Pinhead is not Pinhead, but “Lead Cenobite” (the fans thought “Pinhead” was a better name, and so it stuck). Doug Bradley, who would reprise the role over the many sequels and became a popular horror icon, gets just a few lines, and in one of them he suggests that they might be demons, and thus they might be from Hell. But the viewer can still suss out that the more likely explanation is that they are creatures who inspired our notion of demons, from a world that inspired the notion of Hell. Clive Barker leaves it to the viewer, and that’s perfect, but it’s evocative enough. The comic books and the fan fiction could have chugged along just fine without sequels that exhaustively explain everything from who built the Lament Configuration to who Pinhead really is. (Still, it is nice to have a horror franchise built around an elaborate, Lovecraftian mythology, rather than the more mind-numbing slasher film model.)

Barker actually shoots his film like a comic book, with every scene framed like a comic book panel; no surprise that he’s a talented artist himself. Given how low-budget the film is, the approach lends it a welcome, pulpy punch, so that it sits comfortably beside other cult horror films of its era, such as Re-Animator (1985) and Fright Night (1985). But unlike those films, it has a seriousness to its approach which is very much Clive Barker. There’s some humor in the film, certainly, but for the most part it’s a grim little fable about quests of passion that lead to bloody ends. Sometimes his approach can be overwrought, such as in a montage intercutting Larry grunting and struggling to move a bed upstairs, and his wife daydreaming about sweaty sex with Frank, until we hear her orgasmic screams just as that exposed nail tears through the back of Larry’s hand. Indeed, he seems to want his film to be a graduate thesis on the relationship between pain and ecstasy, but the result can sometimes feel more like Ken Russell sensationalism than anything truly intellectual. And that’s fine. The end result is still very entertaining, and plays like a steamy and gruesome bestseller purchased on an impulse at the grocery store checkout lane.

Barker actually shoots his film like a comic book, with every scene framed like a comic book panel; no surprise that he’s a talented artist himself. Given how low-budget the film is, the approach lends it a welcome, pulpy punch, so that it sits comfortably beside other cult horror films of its era, such as Re-Animator (1985) and Fright Night (1985). But unlike those films, it has a seriousness to its approach which is very much Clive Barker. There’s some humor in the film, certainly, but for the most part it’s a grim little fable about quests of passion that lead to bloody ends. Sometimes his approach can be overwrought, such as in a montage intercutting Larry grunting and struggling to move a bed upstairs, and his wife daydreaming about sweaty sex with Frank, until we hear her orgasmic screams just as that exposed nail tears through the back of Larry’s hand. Indeed, he seems to want his film to be a graduate thesis on the relationship between pain and ecstasy, but the result can sometimes feel more like Ken Russell sensationalism than anything truly intellectual. And that’s fine. The end result is still very entertaining, and plays like a steamy and gruesome bestseller purchased on an impulse at the grocery store checkout lane.

What drew me to Barker was his idea, expressed so frequently in his short stories, that the grotesque can be beautiful. In Hellraiser, these explorations interested me much more than the S&M ideology. Even before Frank has his skin back, Julia’s clearly tempted to jump his (ahem) bones. Similarly, the Cenobites are so fetishistically designed that it’s obvious they think they’re beautiful, by their own unearthly standards. One of the major themes here is that our common definitions (pain/pleasure and ugliness/beauty) are entirely subjective. They’re part of the same continuum, and might easily swap places.

What drew me to Barker was his idea, expressed so frequently in his short stories, that the grotesque can be beautiful. In Hellraiser, these explorations interested me much more than the S&M ideology. Even before Frank has his skin back, Julia’s clearly tempted to jump his (ahem) bones. Similarly, the Cenobites are so fetishistically designed that it’s obvious they think they’re beautiful, by their own unearthly standards. One of the major themes here is that our common definitions (pain/pleasure and ugliness/beauty) are entirely subjective. They’re part of the same continuum, and might easily swap places.

To be honest, these ideas interest me less now, years on, but the film itself is still an impressive debut from a young filmmaker. He would go on to direct Nightbreed (1990), a fascinating but flawed attempt to shift cinematic horror into the broader fantasy genre, and Lord of Illusions (1995), a neo-noir featuring a character from his fiction, supernatural detective Harry D’Amour. He never quite pulled off the boundary-redefining genre film that he was after, but Hellraiser comes closest. (The best Clive Barker film was one he produced, but didn’t direct: Bernard Rose’s Candyman.) To Hellraiser‘s everlasting credit, it’s a horror movie that doesn’t resemble anything that had been made before. It didn’t arise from monster movies or slasher films. It’s a work of inspiration, springing out of a wholly different (and rather unpleasant) dimension. It should have led to something else for the genre…not sequels and toys.