The film opens under the watchful eye of ravens, skulking beneath a gray sky. It’s the late seventeenth century, and the days of the Glorious Revolution. A young man named Ralph Gower (Barry Andrews, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave), tasked with ploughing a field, uncovers a buried, decomposing corpse. Although the remains appear humanoid, the thing is covered with a dark-brown fur. A worm crawls across a still-intact eyeball. Ralph hurries back to the Judge (Patrick Wymark, The Skull), patriarch of the community, to report his findings; but when he returns with the skeptical old man in tow, they can find only find the Reverend Fallowfield (Anthony Ainley, Doctor Who‘s The Master), the youthful minister and schoolteacher, who – beneath the Judge’s suspicious gaze – toys with a pet snake.

The film opens under the watchful eye of ravens, skulking beneath a gray sky. It’s the late seventeenth century, and the days of the Glorious Revolution. A young man named Ralph Gower (Barry Andrews, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave), tasked with ploughing a field, uncovers a buried, decomposing corpse. Although the remains appear humanoid, the thing is covered with a dark-brown fur. A worm crawls across a still-intact eyeball. Ralph hurries back to the Judge (Patrick Wymark, The Skull), patriarch of the community, to report his findings; but when he returns with the skeptical old man in tow, they can find only find the Reverend Fallowfield (Anthony Ainley, Doctor Who‘s The Master), the youthful minister and schoolteacher, who – beneath the Judge’s suspicious gaze – toys with a pet snake.

That night, the weak-willed Peter (Simon Williams, Jabberwocky) arrives at the home of his aunt Isobel (Avice Landone) to introduce his fiancee, a naive and plain-looking farmer’s daughter named Rosalind (Tamara Ustinov). Both Isobel and the Judge (who’s staying for the evening) express strong disapproval at the union, and cruel condescension toward the girl; but Peter appeals on her behalf and she’s permitted to spend the night in the attic. While the girl retires, a drunken Judge confesses to Peter that he was once Isobel’s lover; doubtless they’re sleeping together still. Later that night, Rosalind, locked in the attic, begins to scream in terror. By the time her door can be broken down, she’s discovered in a raving state; as she’s being dragged out of the house, Peter glimpses her hand, which appears to be transformed into sharp talons. The next night, Peter decides to spend the night in the attic. The floorboards begins to creak and open, and he glimpses a furry claw struggling free. He slams the boards shut and falls unconscious into bed; and later awakens to find that own hand has transformed into a hideous claw. When the Judge enters the attic, he finds that Peter has cut off his own (now ordinary and human) hand.

That night, the weak-willed Peter (Simon Williams, Jabberwocky) arrives at the home of his aunt Isobel (Avice Landone) to introduce his fiancee, a naive and plain-looking farmer’s daughter named Rosalind (Tamara Ustinov). Both Isobel and the Judge (who’s staying for the evening) express strong disapproval at the union, and cruel condescension toward the girl; but Peter appeals on her behalf and she’s permitted to spend the night in the attic. While the girl retires, a drunken Judge confesses to Peter that he was once Isobel’s lover; doubtless they’re sleeping together still. Later that night, Rosalind, locked in the attic, begins to scream in terror. By the time her door can be broken down, she’s discovered in a raving state; as she’s being dragged out of the house, Peter glimpses her hand, which appears to be transformed into sharp talons. The next night, Peter decides to spend the night in the attic. The floorboards begins to creak and open, and he glimpses a furry claw struggling free. He slams the boards shut and falls unconscious into bed; and later awakens to find that own hand has transformed into a hideous claw. When the Judge enters the attic, he finds that Peter has cut off his own (now ordinary and human) hand.

Those misshapen remains are found once more in the field, this time by teenage beauty Angel Blake (Linda Hayden, Taste the Blood of Dracula) and her young companions. Keeping trophies from the corpse in a pouch, she holds to the items with a strange possessiveness. In class, the Reverend Fallowfield discovers the pouch, and is disturbed by the taloned finger he finds within. Within the next few days, his class will grow smaller, as the children begin to disappear, and others begin acting with an inexplicable but unsettling purpose.

Those misshapen remains are found once more in the field, this time by teenage beauty Angel Blake (Linda Hayden, Taste the Blood of Dracula) and her young companions. Keeping trophies from the corpse in a pouch, she holds to the items with a strange possessiveness. In class, the Reverend Fallowfield discovers the pouch, and is disturbed by the taloned finger he finds within. Within the next few days, his class will grow smaller, as the children begin to disappear, and others begin acting with an inexplicable but unsettling purpose.

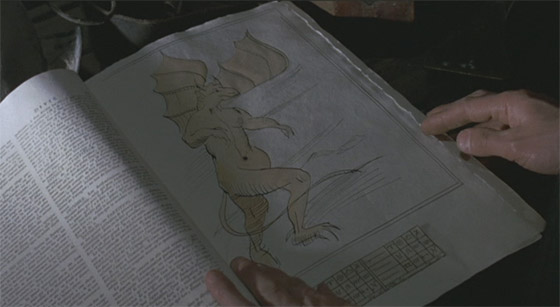

After the Judge consults a tome of demonology with the local doctor (Howard Goorney), he suspects that a Satanic evil is beginning to take grip in the town. But he’s abruptly called away to business in London; donning a feathered cap, the Judge boards a carriage and prepares to leave. A frantic Ralph accuses the Judge of desertion, but he promises to return “when the time is ripe.” Ominously, he instructs Ralph: “You must have patience. Even while people die, only thus can the whole evil be destroyed. You must let it grow.”

After the Judge consults a tome of demonology with the local doctor (Howard Goorney), he suspects that a Satanic evil is beginning to take grip in the town. But he’s abruptly called away to business in London; donning a feathered cap, the Judge boards a carriage and prepares to leave. A frantic Ralph accuses the Judge of desertion, but he promises to return “when the time is ripe.” Ominously, he instructs Ralph: “You must have patience. Even while people die, only thus can the whole evil be destroyed. You must let it grow.”

And grow it does – far beyond the Judge’s expectations. Young Mark Vespers, who keeps with him some of the mysterious bones, begins to fall ill. He’s summoned by Angel and her friends to a gathering, where he’s blindfolded for a “game.” Angel strangles him to death as the others watch; his mother later discovers his body in a woodshed, crushed beneath a pile of kindling. That evening, Angel pays a visit to the Reverend Fallowfield and attempts to seduce him. When he rejects her advances, she accuses him of rape, as well as Mark’s murder. Squire Middleton (James Hayter, Oliver!), in charge of the village in the Judge’s absence, has the Reverend arrested following Mark’s funeral.

And grow it does – far beyond the Judge’s expectations. Young Mark Vespers, who keeps with him some of the mysterious bones, begins to fall ill. He’s summoned by Angel and her friends to a gathering, where he’s blindfolded for a “game.” Angel strangles him to death as the others watch; his mother later discovers his body in a woodshed, crushed beneath a pile of kindling. That evening, Angel pays a visit to the Reverend Fallowfield and attempts to seduce him. When he rejects her advances, she accuses him of rape, as well as Mark’s murder. Squire Middleton (James Hayter, Oliver!), in charge of the village in the Judge’s absence, has the Reverend arrested following Mark’s funeral.

“She’s a devil, that Angel. She be no friend of mine,” Cathy Vespers had told her brother Mark shortly before his death. Truer than she knows, Cathy is next targeted by Angel and her followers. One afternoon, after parting ways with her beloved Ralph, Cathy is accosted by two of her schoolmates, and delivered to Angel. Angel forces to Cathy to participate in a Satanic ceremony where they pray to a demon called “Behemoth.” A cloaked creature is summoned, lurking in the shadows and whispering hoarse instructions, as Cathy undergoes an agonized transformation, growing dark fur upon her back. To conclude the ceremony, Cathy is brutally raped by one of the village boys, and then stabbed with a dagger by Angel.

At least her murder forces Squire Middleton to believe the Reverend Fallowfield’s version of events, and release him from imprisonment. Focus now turns to finding Angel Blake and her devil’s cult. A mob roots out one of their members, Margaret, and nearly drowns her to prove that she’s a witch. Ralph rescues her, and discovers a patch of fur upon her leg. “That’s what they call the devil’s skin.” The Doctor is summoned, and after some reluctance, he performs an operation in which the skin is cut free. For all this, Margaret only pays Ralph back by trying to seduce him into joining Angel’s coven. He rejects her offers, and she flees to find Angel.

At least her murder forces Squire Middleton to believe the Reverend Fallowfield’s version of events, and release him from imprisonment. Focus now turns to finding Angel Blake and her devil’s cult. A mob roots out one of their members, Margaret, and nearly drowns her to prove that she’s a witch. Ralph rescues her, and discovers a patch of fur upon her leg. “That’s what they call the devil’s skin.” The Doctor is summoned, and after some reluctance, he performs an operation in which the skin is cut free. For all this, Margaret only pays Ralph back by trying to seduce him into joining Angel’s coven. He rejects her offers, and she flees to find Angel.

Peter, now with a stump for a hand, rides out to find the Judge and bring him back to the village. Once the Judge learns that children are murdering one another, he agrees to return, but warns: “Understand, I will use undreamed-of measures.” He organizes a search party, with savage dogs to track through the woods. They find Margaret, who has been rejected by Angel since her devil’s skin has been removed. She’s tortured until she confesses the site of the next gathering. As the Judge prepares to destroy the cult – and the Behemoth they are both summoning and reconstructing, one piece of flesh at a time – Ralph is horrified to discover that his own foot is now covered with dark fur. He hurries to join the Judge to put an end to the rising evil before it corrupts his own soul.

Peter, now with a stump for a hand, rides out to find the Judge and bring him back to the village. Once the Judge learns that children are murdering one another, he agrees to return, but warns: “Understand, I will use undreamed-of measures.” He organizes a search party, with savage dogs to track through the woods. They find Margaret, who has been rejected by Angel since her devil’s skin has been removed. She’s tortured until she confesses the site of the next gathering. As the Judge prepares to destroy the cult – and the Behemoth they are both summoning and reconstructing, one piece of flesh at a time – Ralph is horrified to discover that his own foot is now covered with dark fur. He hurries to join the Judge to put an end to the rising evil before it corrupts his own soul.

A product of Tigon British Film Productions, The Blood on Satan’s Claw could almost be a companion-piece to the studio’s earlier masterpiece, Witchfinder General (1968). Like that film, it’s a portrait of a community enveloped in Satanic hysteria; unlike Witchfinder, the hysteria has a valid cause. Not that Satan’s Claw doesn’t acknowledge the dangers and the hypocrisy of a town turning against its own in the cause of rooting out evil. The Judge upholds moral purity – and condemns Peter and his fiancee Rosalind under his suspicions that they’ve been sleeping out of wedlock – though it’s pretty evident he’s having an affair with Peter’s aunt Isobel. He allows Isobel to savagely beat Rosalind when the girl is in hysterics; and later he has no compunction about threatening Margaret with his savage dogs until she confesses the information he needs. The Judge may be the Van Helsing of the piece (the only one with the skills and knowledge to defeat Behemoth), but the hero is clearly Ralph Gower, the only one who suspects the evil from the start, yet can still demonstrate empathy when Margaret is nearly drowned by a mob who believes that a witch will always float. It’s a Satanic horror film that’s sophisticated enough to temper its sensationalism with sobriety.

A product of Tigon British Film Productions, The Blood on Satan’s Claw could almost be a companion-piece to the studio’s earlier masterpiece, Witchfinder General (1968). Like that film, it’s a portrait of a community enveloped in Satanic hysteria; unlike Witchfinder, the hysteria has a valid cause. Not that Satan’s Claw doesn’t acknowledge the dangers and the hypocrisy of a town turning against its own in the cause of rooting out evil. The Judge upholds moral purity – and condemns Peter and his fiancee Rosalind under his suspicions that they’ve been sleeping out of wedlock – though it’s pretty evident he’s having an affair with Peter’s aunt Isobel. He allows Isobel to savagely beat Rosalind when the girl is in hysterics; and later he has no compunction about threatening Margaret with his savage dogs until she confesses the information he needs. The Judge may be the Van Helsing of the piece (the only one with the skills and knowledge to defeat Behemoth), but the hero is clearly Ralph Gower, the only one who suspects the evil from the start, yet can still demonstrate empathy when Margaret is nearly drowned by a mob who believes that a witch will always float. It’s a Satanic horror film that’s sophisticated enough to temper its sensationalism with sobriety.

It’s also intensely realistic, from an authentic period feel to an unadorned depiction of witchcraft and magic; even when Behemoth appears, the effect is creepy but understated. The budget couldn’t extend to special effects, but that’s an advantage: the lack of overtly fantastic imagery helps the film retain an earthy feel of pagan horror. There are things out in those woods, and beneath those ploughed fields, and in those misty ruins – you can relate to the growing superstitious dread of the townsfolk, because it’s tangible onscreen. Director Piers Haggard, a veteran of British television, commendably evokes exactly what the screenplay (by Robert Wynne-Simmons) requires. If there’s a flaw in the film, it’s only that the mechanics of obeying and summoning Behemoth, via the devil’s skin, is confusing; and one gets the sense that certain scenes were reorganized – or other scenes omitted – as the plot rushes forward. But what the film sometimes loses in coherency, it gains in a feeling of terror toward the unknown.

It’s also intensely realistic, from an authentic period feel to an unadorned depiction of witchcraft and magic; even when Behemoth appears, the effect is creepy but understated. The budget couldn’t extend to special effects, but that’s an advantage: the lack of overtly fantastic imagery helps the film retain an earthy feel of pagan horror. There are things out in those woods, and beneath those ploughed fields, and in those misty ruins – you can relate to the growing superstitious dread of the townsfolk, because it’s tangible onscreen. Director Piers Haggard, a veteran of British television, commendably evokes exactly what the screenplay (by Robert Wynne-Simmons) requires. If there’s a flaw in the film, it’s only that the mechanics of obeying and summoning Behemoth, via the devil’s skin, is confusing; and one gets the sense that certain scenes were reorganized – or other scenes omitted – as the plot rushes forward. But what the film sometimes loses in coherency, it gains in a feeling of terror toward the unknown.

Tigon specialized in exploitation films, and though the film delivers on that score (notably in some graphic nudity, and the gory operation to remove the devil’s skin from Margaret), it’s an unusually classy effort for a low-budget British horror film from the early 70’s – when product of this sort began to look cheaper, uglier, and sleazier. The Blood on Satan’s Claw is gifted with a lushly romantic score by Marc Wilkinson, strongly reminiscent of the work of James Bernard for Hammer Films, though it has a queasy and eerie cadence. What’s most welcome is that it’s an actor’s film. Linda Hayden, who had previously played a demented underage sexpot in Baby Love (1968) and an innocent girl corrupted into patricide in Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), is nothing short of spellbinding as the wicked Angel Blake. She transforms gradually from an earthy peasant girl to a sexy nymphet, and finally to a repellent pagan priestess, all the while dominating the teenagers who surround her; her performance is confident, erotic, and electric. (It’s unfortunate that, as the British film industry waned, she’d be reduced to cruder exploitation for the remainder of the 70’s. She deserved more roles like this one.) But the film is owned by Patrick Wymark. Wymark, who died the year this was filmed, manages a believably human knot of contradictions: he’s commanding, frightening, loathsome, swashbuckling, and thrillingly heroic. He recalls Andrew Keir in Quatermass and the Pit (1967) or Andre Morell in Plague of the Zombies (1966), but with a darker, somewhat sadistic streak informed by Vincent Price’s Witchfinder General. It’s a triumphant performance in a film that would go underseen, and unchampioned, for years.

Tigon specialized in exploitation films, and though the film delivers on that score (notably in some graphic nudity, and the gory operation to remove the devil’s skin from Margaret), it’s an unusually classy effort for a low-budget British horror film from the early 70’s – when product of this sort began to look cheaper, uglier, and sleazier. The Blood on Satan’s Claw is gifted with a lushly romantic score by Marc Wilkinson, strongly reminiscent of the work of James Bernard for Hammer Films, though it has a queasy and eerie cadence. What’s most welcome is that it’s an actor’s film. Linda Hayden, who had previously played a demented underage sexpot in Baby Love (1968) and an innocent girl corrupted into patricide in Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), is nothing short of spellbinding as the wicked Angel Blake. She transforms gradually from an earthy peasant girl to a sexy nymphet, and finally to a repellent pagan priestess, all the while dominating the teenagers who surround her; her performance is confident, erotic, and electric. (It’s unfortunate that, as the British film industry waned, she’d be reduced to cruder exploitation for the remainder of the 70’s. She deserved more roles like this one.) But the film is owned by Patrick Wymark. Wymark, who died the year this was filmed, manages a believably human knot of contradictions: he’s commanding, frightening, loathsome, swashbuckling, and thrillingly heroic. He recalls Andrew Keir in Quatermass and the Pit (1967) or Andre Morell in Plague of the Zombies (1966), but with a darker, somewhat sadistic streak informed by Vincent Price’s Witchfinder General. It’s a triumphant performance in a film that would go underseen, and unchampioned, for years.

But over the decades it’s found the cult status it long deserved. The Blood on Satan’s Claw is exactly the sort of film that rival studios Hammer and Amicus ought to have been making in the early 70’s: a daring, pitch-dark, straight-faced horror film aimed at adults. In the liner notes to the 2010 U.K. DVD re-release, Darius Drewe Shimon cleverly isolates Hammer’s (unpopular) Straight On Till Morning (1972) as one of the few genre films from the period that could match Claw in its depiction of grim, unexploitative violence. Both are chilling and disturbing, but the difference is that Claw is more likely to beg a revisit. You’ll want to return to Wymark’s cold-blooded Judge, to Hayden’s seductive but mad-eyed stare, to the chilly fields and woods haunted by Behemoth and his underlings. This is 1970’s genre filmmaking at its best.

But over the decades it’s found the cult status it long deserved. The Blood on Satan’s Claw is exactly the sort of film that rival studios Hammer and Amicus ought to have been making in the early 70’s: a daring, pitch-dark, straight-faced horror film aimed at adults. In the liner notes to the 2010 U.K. DVD re-release, Darius Drewe Shimon cleverly isolates Hammer’s (unpopular) Straight On Till Morning (1972) as one of the few genre films from the period that could match Claw in its depiction of grim, unexploitative violence. Both are chilling and disturbing, but the difference is that Claw is more likely to beg a revisit. You’ll want to return to Wymark’s cold-blooded Judge, to Hayden’s seductive but mad-eyed stare, to the chilly fields and woods haunted by Behemoth and his underlings. This is 1970’s genre filmmaking at its best.