“The more adventurous among you may remember our previous excursions into the macabre. Our visits to haunted hills, to Tinglers, and to ghosts. This time we have an even stranger tale to unfold…The story of a lovable group of people who just happen to be – Homicidal.”

“The more adventurous among you may remember our previous excursions into the macabre. Our visits to haunted hills, to Tinglers, and to ghosts. This time we have an even stranger tale to unfold…The story of a lovable group of people who just happen to be – Homicidal.”

Homicidal (1961) is such a ridiculous little film that it doesn’t survive without context, like a fish gasping for air on the beach. And when I say ridiculous, I mean true, shoot-for-the-moon absurdity, simultaneously audacious and shameless. That context says everything about the choices the film makes, and that context can be provided in a single word: Psycho. Alfred Hitchcock’s film had descended like a cinematic blitzkrieg in 1960, forever altering the public’s perception of what a successful suspense thriller should be – while giving birth to the “slasher” film. Famously, Hitchcock had insisted that no one be permitted to enter the theater once the film started. “It is required that you see Psycho from the very beginning!” urged one of its posters. “Any spurious attempts to enter by side doors, fire escapes, or ventilating shafts will be met by force.” Hitchcock had a genuine need to protect the film’s final twist, as well as preserve the integrity of the film as a whole by insisting attendees not wander in and out, but sit down and watch the thing from beginning to end – but, ever the consummate showman, he achieved this end through publicity stunts. The audience went along with it. It was an event, and they loved it; though the film itself was, perhaps, quite a bit more shocking than they’d expected.

Producer/director William Castle, as always, had his eyes on Hitch. His previous film, 13 Ghosts (1960), was released only one month prior to Psycho, and then became instantly dated. Unwittingly, Castle was still making films of the 50’s; Hitch had just changed the game. Naturally his next project would need to give audiences what they now expected from their horror films. Despite his new approach, Castle once more turned to screenwriter Robb White, who had penned 13 Ghosts, and asked for a take on Psycho. That’s exactly what you get in Homicidal: Psycho in a distorted mirror, borrowing liberally, while upping the ante for on-screen blood and sexuality. And, like so many thrillers which would follow from the 60’s onward, it failed to surpass the original, lurking only in its shadow.

Producer/director William Castle, as always, had his eyes on Hitch. His previous film, 13 Ghosts (1960), was released only one month prior to Psycho, and then became instantly dated. Unwittingly, Castle was still making films of the 50’s; Hitch had just changed the game. Naturally his next project would need to give audiences what they now expected from their horror films. Despite his new approach, Castle once more turned to screenwriter Robb White, who had penned 13 Ghosts, and asked for a take on Psycho. That’s exactly what you get in Homicidal: Psycho in a distorted mirror, borrowing liberally, while upping the ante for on-screen blood and sexuality. And, like so many thrillers which would follow from the 60’s onward, it failed to surpass the original, lurking only in its shadow.

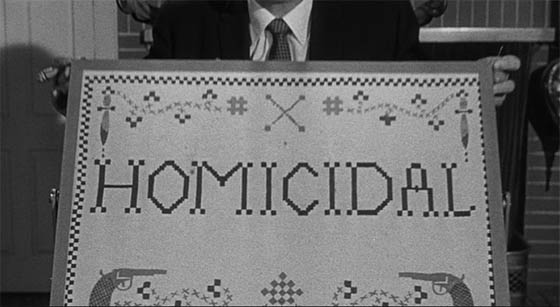

The film starts with a now-requisite introduction from Castle himself; he shows off his needlework skills, pricks his finger, and looks at it with delight: “Aah – blood!” As though he just discovered it, and now he can fill his movies with it. With The Tingler (1959) and its bathtub filled with red, red blood, he’d already pushed some boundaries in this direction, but Homicidal takes Hitch’s lead and features, toward the very start of the film, a very graphic stabbing with blood pumping freely from wounds. We aren’t in 13 Ghosts anymore; hide the kids. The killing occurs completely out of the blue. In the Psycho-styled prologue, Emily (TV actress Joan Marshall, credited as “Jean Arless”), a beautiful blonde, checks into a hotel and immediately strikes up a flirtation with the bellboy. When he shows interest, she directly offers him $2000 if she’ll marry him that evening. He reluctantly agrees, and she drives him off to see a justice of the peace, waking the man in the middle of the night, and coercing him into marrying them. (His bored wife plays the “Wedding March” half-heartedly on the organ, in a nice bit of Castle humor.) After the ceremony, the justice leans forward to kiss the bride. Emily’s eyes widen in horror. She pulls out a knife and stabs the justice several times in the belly, while his wife and the bellboy watch, paralyzed with shock; then she flees. If you can’t already count off the Psycho steals in these opening scenes – Janet Leigh-ish blonde in a sleazy hotel room (with a brief glimpse of brassiere); cash which might be stolen; a brutal stabbing without warning – then you can hardly miss the one which comes next: Emily, behind the wheel, racing through the night, nervously sees police lights in the rear-view mirror. She pulls over, but the cop was actually trying to nab the driver just ahead of her. She sits on the side of the road, catches her breath, and pulls away.

The film starts with a now-requisite introduction from Castle himself; he shows off his needlework skills, pricks his finger, and looks at it with delight: “Aah – blood!” As though he just discovered it, and now he can fill his movies with it. With The Tingler (1959) and its bathtub filled with red, red blood, he’d already pushed some boundaries in this direction, but Homicidal takes Hitch’s lead and features, toward the very start of the film, a very graphic stabbing with blood pumping freely from wounds. We aren’t in 13 Ghosts anymore; hide the kids. The killing occurs completely out of the blue. In the Psycho-styled prologue, Emily (TV actress Joan Marshall, credited as “Jean Arless”), a beautiful blonde, checks into a hotel and immediately strikes up a flirtation with the bellboy. When he shows interest, she directly offers him $2000 if she’ll marry him that evening. He reluctantly agrees, and she drives him off to see a justice of the peace, waking the man in the middle of the night, and coercing him into marrying them. (His bored wife plays the “Wedding March” half-heartedly on the organ, in a nice bit of Castle humor.) After the ceremony, the justice leans forward to kiss the bride. Emily’s eyes widen in horror. She pulls out a knife and stabs the justice several times in the belly, while his wife and the bellboy watch, paralyzed with shock; then she flees. If you can’t already count off the Psycho steals in these opening scenes – Janet Leigh-ish blonde in a sleazy hotel room (with a brief glimpse of brassiere); cash which might be stolen; a brutal stabbing without warning – then you can hardly miss the one which comes next: Emily, behind the wheel, racing through the night, nervously sees police lights in the rear-view mirror. She pulls over, but the cop was actually trying to nab the driver just ahead of her. She sits on the side of the road, catches her breath, and pulls away.

Of course, Marion Crane was just a petty thief, not a killer. Emily is psycho, and Castle seemingly gives the game away this early in the film; but there is more going on than meets the eye. For these opening scenes, Emily’s been using the false name of Miriam Webster (a name I cannot type without laughing) – we soon learn that the real Miriam (Patricia Breslin) is the daughter of Helga, the wheelchair-bound invalid whom Emily cares for in Solvang, California. As police begin circulating a description of the homicidal maniac on the loose, and that she’s been using the name “Miriam Webster,” Miriam and her pharmacist boyfriend Karl (Glenn Corbett, The Pirates of Blood River) begin to suspect Emily. Miriam’s half-brother, Warren, is dubious – but we also learn that he just secretly married Emily. Meanwhile, the mute Helga fears for her life as Emily exhibits increasingly deranged behavior – like the way she sensually strokes the little knife she keeps in her briefcase – but Helga’s frantic facial contortions fail to significantly warn those around her (apparently, everyone thinks her default expression is panic, so they pay no mind). Did I mention there’s a hefty inheritance in play as well, which either Miriam or Warren stands to win?

Of course, Marion Crane was just a petty thief, not a killer. Emily is psycho, and Castle seemingly gives the game away this early in the film; but there is more going on than meets the eye. For these opening scenes, Emily’s been using the false name of Miriam Webster (a name I cannot type without laughing) – we soon learn that the real Miriam (Patricia Breslin) is the daughter of Helga, the wheelchair-bound invalid whom Emily cares for in Solvang, California. As police begin circulating a description of the homicidal maniac on the loose, and that she’s been using the name “Miriam Webster,” Miriam and her pharmacist boyfriend Karl (Glenn Corbett, The Pirates of Blood River) begin to suspect Emily. Miriam’s half-brother, Warren, is dubious – but we also learn that he just secretly married Emily. Meanwhile, the mute Helga fears for her life as Emily exhibits increasingly deranged behavior – like the way she sensually strokes the little knife she keeps in her briefcase – but Helga’s frantic facial contortions fail to significantly warn those around her (apparently, everyone thinks her default expression is panic, so they pay no mind). Did I mention there’s a hefty inheritance in play as well, which either Miriam or Warren stands to win?

There are twists. Oh, there are twists. As with so many of the thrillers which would follow in Psycho‘s wake, particularly in the Italian giallo films of the 60’s and 70’s, a key twist involves sexual psychology – but you can discover that for yourself. Needless to say, the impact of Homicidal‘s ultimate revelation has been diluted by the passage of time (and used by other films), but it must have been pretty jaw-dropping in 1961. To get away with his twist, Castle cheats a bit, but in doing so, you might not see it coming.

There are twists. Oh, there are twists. As with so many of the thrillers which would follow in Psycho‘s wake, particularly in the Italian giallo films of the 60’s and 70’s, a key twist involves sexual psychology – but you can discover that for yourself. Needless to say, the impact of Homicidal‘s ultimate revelation has been diluted by the passage of time (and used by other films), but it must have been pretty jaw-dropping in 1961. To get away with his twist, Castle cheats a bit, but in doing so, you might not see it coming.

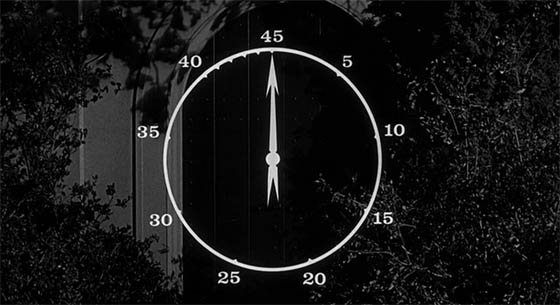

It was obligatory, of course, for Castle to promote the film by putting up signs stating “No One Admitted During the Last 15 Minutes of Homicidal.” He couldn’t let himself be outdone by Hitchcock. In a promotional film, he warned, “Ladies and gentlemen, please do not reveal the ending of Homicidal to your friends. Because if you do, they will kill you. And if they don’t, I will.” (Is this the first time in history a director actually threatened to murder his audience?) Of course, he needed a trademark Castle innovation/gimmick embedded in his film. This was the “Fright Break.” Just before the climax of the film (as Miriam slowly approaches a house where evil dwells), a beating heart is heard pounding on the soundtrack, and a clock is suddenly, jarringly superimposed on the screen. As it ticks down from forty-five seconds, Castle’s disembodied voice declares, “This is the Fright Break! You hear that sound? It’s the sound of a heartbeat. A frightened, terrified heart. Is it beating faster than your heart, or slower? This heart is going to beat for another twenty-five seconds to allow anyone to leave this theater who is too frightened to see the end of the picture. Ten seconds more and we go into the house. It’s now or never. Five, four – you’re a brave audience…” Should you decide to run from the theater during the Fright Break, you could receive a full refund at the Coward’s Corner, a prop built to Castle’s specifications by the management. Just stick your head out of the little window in the Coward’s Corner, right next to the words, “Nervous, tense, green with fear? Your money back, over here!” Not too many people took Castle up on this offer.

It was obligatory, of course, for Castle to promote the film by putting up signs stating “No One Admitted During the Last 15 Minutes of Homicidal.” He couldn’t let himself be outdone by Hitchcock. In a promotional film, he warned, “Ladies and gentlemen, please do not reveal the ending of Homicidal to your friends. Because if you do, they will kill you. And if they don’t, I will.” (Is this the first time in history a director actually threatened to murder his audience?) Of course, he needed a trademark Castle innovation/gimmick embedded in his film. This was the “Fright Break.” Just before the climax of the film (as Miriam slowly approaches a house where evil dwells), a beating heart is heard pounding on the soundtrack, and a clock is suddenly, jarringly superimposed on the screen. As it ticks down from forty-five seconds, Castle’s disembodied voice declares, “This is the Fright Break! You hear that sound? It’s the sound of a heartbeat. A frightened, terrified heart. Is it beating faster than your heart, or slower? This heart is going to beat for another twenty-five seconds to allow anyone to leave this theater who is too frightened to see the end of the picture. Ten seconds more and we go into the house. It’s now or never. Five, four – you’re a brave audience…” Should you decide to run from the theater during the Fright Break, you could receive a full refund at the Coward’s Corner, a prop built to Castle’s specifications by the management. Just stick your head out of the little window in the Coward’s Corner, right next to the words, “Nervous, tense, green with fear? Your money back, over here!” Not too many people took Castle up on this offer.

As a theater-going event, Homicidal doubtless delivered the goods. As a film, it doesn’t hold up too well. Since the Castle gimmick comes so late in the film, and because the film’s tone has heretofore been so much more serious than The Tingler or 13 Ghosts, the Fright Break is giggle-inducing but distracting as hell. The film survives less as a psychosexual thriller and more as camp artifact, though surely it had some impact: those horror films in ensuing decades with an over-the-top, rug-pulling twist probably owe more to Homicidal than Psycho. As cinema entered the 1960’s, and the horror genre further pushed the envelope, could Castle adapt his approach? To be continued.

As a theater-going event, Homicidal doubtless delivered the goods. As a film, it doesn’t hold up too well. Since the Castle gimmick comes so late in the film, and because the film’s tone has heretofore been so much more serious than The Tingler or 13 Ghosts, the Fright Break is giggle-inducing but distracting as hell. The film survives less as a psychosexual thriller and more as camp artifact, though surely it had some impact: those horror films in ensuing decades with an over-the-top, rug-pulling twist probably owe more to Homicidal than Psycho. As cinema entered the 1960’s, and the horror genre further pushed the envelope, could Castle adapt his approach? To be continued.