Jean Rollin immediately followed The Nude Vampire (1970) with another low-budget piece of vampire erotica, Shiver of the Vampires (Le frisson des vampires, 1971), and although he would continue to pursue the same Gothic obsessions until his death in 2010, it’s easy to see Shiver as completing a trilogy. It’s also the best of this first cycle by far, as Rollin finally achieves a style of storytelling ideally suited to his violent and sexual daydreams: it’s an adult fairy tale, unpretentious, with touches of genuinely funny camp, and heaps of exploitation to satisfy the grindhouse market. It may be flawed as “serious cinema” in the director’s usual ways – some charmingly awkward acting, gratuitous nudity, and absurdly-staged action – but Rollin’s knack for searing images is finally wedded to a worthy story, one that taps into archetypal fears, longings, and paranoia. It’s a complete original, and I love it without apology.

Jean Rollin immediately followed The Nude Vampire (1970) with another low-budget piece of vampire erotica, Shiver of the Vampires (Le frisson des vampires, 1971), and although he would continue to pursue the same Gothic obsessions until his death in 2010, it’s easy to see Shiver as completing a trilogy. It’s also the best of this first cycle by far, as Rollin finally achieves a style of storytelling ideally suited to his violent and sexual daydreams: it’s an adult fairy tale, unpretentious, with touches of genuinely funny camp, and heaps of exploitation to satisfy the grindhouse market. It may be flawed as “serious cinema” in the director’s usual ways – some charmingly awkward acting, gratuitous nudity, and absurdly-staged action – but Rollin’s knack for searing images is finally wedded to a worthy story, one that taps into archetypal fears, longings, and paranoia. It’s a complete original, and I love it without apology.

Newlyweds Isle (Sandra Julien) and Antoine (Jean-Marie Durand) arrive for a honeymoon at the manor of her deceased cousins.

By 1971, lesbian vampire films were all the rage. Hammer was furiously tearing bodices with its Carmilla-inspired “Karnstein” films (The Vampire Lovers, Lust for a Vampire, Twins of Evil, 1970-1971), and Jess Franco was seducing grindhouse audiences with Vampyros Lesbos (1971). Rollin had a niche to exploit; though his two previous films didn’t particularly emphasize lesbianism, Shiver of the Vampires would. Michel Delahaye, who played the lord of the vampires (or, rather, “mutants”) in The Nude Vampire would return in a very similar role. Rollin was so enamored with the image of the Castel twins walking through empty castle corridors holding candelabras that he wrote them identical roles here; however, Catherine Castel was pregnant, so she was replaced by Kuelan Herce – who is neither blonde nor Caucasian, but is posed in every shot beside Marie-Pierre Castel (credited as just “Marie-Pierre”) as though they are playing twins. Somehow, this adds to the enjoyment. The gorgeous Sandra Julien plays Isle (“Isa” in the American dub), who is introduced in a pure-white wedding dress, and is subsequently corrupted into vampirism and bloodlust over the film’s 96 minutes. She and her young husband, Antoine (Jean-Marie Durand), intend to spend their honeymoon at the rural castle occupied by her two cousins, but as soon as they arrive in town, they learn from a local, Isabelle (Nicole Nancel), that the cousins – whom Isabelle loved – have just been buried. So the couple expects to find the castle vacant, but are greeted instead by the twins-who-are-not.

The vampire Isolde (Dominique) emerges from a clock when it strikes midnight.

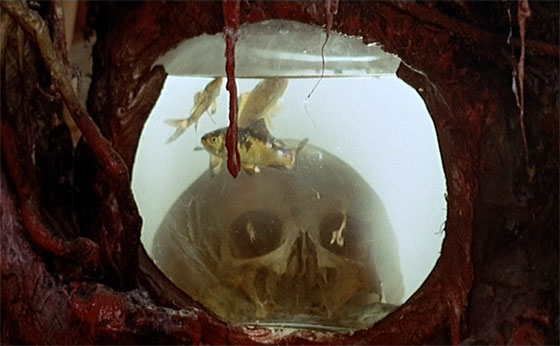

Though it’s their wedding night, Isle is grieving her cousins, and asks to sleep alone. As her bedroom clock tolls for midnight, its door swings open to reveal a vampire woman, Isolde (Dominique), tucked inside, her arms wrapped around her body like a mummy. She slinks out of the clock and greets the nude Isle, then leads her down into the graveyard for a secret ceremony in which Isle is persuaded to drink from a goblet of blood. Antoine witnesses this, but can find no trace of the vampire the next morning. When he explores a library alone, the books come to life, flying from all shelves and burying him beneath a pile. Then Isle’s cousins return, as played by Delahaye and Jacques Robiolles. They don’t have much to say about their unexpected resurrection, but regale the two newlyweds with their researches into ancient religions, in particular the worship of the goddess Isis. Their dialogue is delivered by having each actor duck into the camera’s frame at alternate turns, until finally they both try to squeeze in at once – like cartoon characters. Later we learn that they were vampire hunters who became vampires themselves, and now serve Isolde, who has been recently reborn. That night, Isle, naked, waits in anticipation by the door of her clock. When she reluctantly drifts back toward the bed, Isolde suddenly emerges from the curtains behind it, and bites Isle on the neck. So ravished, Isle collapses onto the sheets.

The castle servants, played by Marie-Pierre Castel and Kuelan Herce.

We learn that Isabelle, the local girl, was the favorite of the two vampire cousins, who commanded her through the howls of their dog Anubis. When she is called to the castle once more, it’s to be usurped by Isle, whom the vampiress Isolde prefers. Isolde kills Isabelle through an embrace; her pasties, sharp as spikes, stab her victim through the nipples. It’s a Surrealist’s idea of a murder scene. Before a thorny-framed work of art representing two bloody bite-marks, the vampiress scolds the two ex-vampire hunters, calling them “bourgeois vampires.” Apparently there’s a subtle caste system at work. Born of vampires, Isolde considers herself to be a “wandering vampire,” a superior specimen and worthy to rule. (One wonders if Anne Rice watched this film and took notes.) The two female servants are mortals enslaved by the vampires – as any horror fan knows, a vampire always relies upon human assistance to keep the crypt safe during daylight hours. And so, while the two maids secretly wish to escape the rule of their masters, the two male vampires resentfully plot against Isolde, Isle prepares herself for a life of immortality, and Antoine…well, Antoine can’t even get his car started so he can get the hell out.

Jacques Robiolles and Michel Delahaye, as the ex-vampire hunters now serving Isolde, greet Antoine and Isle.

There’s a lovely moment, set in daylight, when Isle encounters a dead dove which Antoine has accidentally shot in the gardens surrounding the castle. When she’s away from her husband, she drinks the blood of the bird, and drops its body upon the lid of a coffin. The smell of blood wakes up Isolde, hidden inside, and she asks Isle if she will destroy her by opening the lid and exposing her to the sunlight. Isle stands over the coffin, staring at it, uncertain – trapped between her hypnotized devotion to the vampire and some vestiges of personal will. She decides not to open the coffin. Soon Antoine is fetching her sunglasses and she’s refusing to leave her bedroom. This marriage is pretty much over.

Isle, with a touch of bird blood still on her lips, dons sunglasses to endure the daylight.

As far as Rollin films go, the ending is almost exhilarating. Inevitably, it takes you to the same beach that figured into the conclusions of Rape of the Vampire and The Nude Vampire; the repetition by now has a lyrical quality. Better still, we’ve come to at least understand the characters and the stakes (pun intended); the conclusion is emotionally satisfying without abandoning the film’s fable-like tone. The earlier films had an improvisational jazz score, which perhaps suited the surrealistic shenanigans; but Shiver of the Vampires isn’t jazz, it’s rock and roll. A group of young musicians calling themselves Acanthus provided Rollin with a score that combined elements of psychedelic and progressive rock, the perfect accompaniment to candelabra-marching in diaphanous nightgowns through castle corridors and cemeteries lit by red and blue spotlights. Finders Keepers Records released an LP and CD of the score last year, with French comic artist Phillip Druillet’s beautiful poster art on the cover. The Acanthus tracks are interspersed with dialogue from the English dub and the canine shrieks of Anubis. (It’s become requisite October listening for me already.)

The vampires' castle at night.

Goth label Redemption has been the primary purveyor of Rollin on DVD in the last decade or so; they’re passable releases, but rumor has it that Kino has acquired the rights to Rollin’s filmography, with Blu-Rays on the way. The upgrade should come with some new attention paid to this most esoteric of cult filmmakers, but I don’t know that the majority of his work will be that much more “accessible” – not truly. Because with Shiver of the Vampires, Rollin was dispensing with Dracula clichés while perfecting his own personal mythology, writing from the gut, stringing together the simplest possible narrative which would allow him to exhibit his spellbinding and bizarre images. It is modern in a way which many horror films of the period were not; it’s almost punk art. The result is a cinema which is not about vampires, but for them.