Often cited as Russia’s first horror film, Viy (1967) faithfully adapts a 19th-century tale by Nikolai Gogol which, like the tales of Poe and Hawthorne, became a classic of modern folklore. The opening titles state that it’s directed by “graduates of Advanced Film Directors courses”: Georgi Kropachyov and Konstantin Yershov, though the better-known name attached to the film is credited as “Artistic Director and Special Effects Designer.” That would be Aleksandr Ptushko. Ptushko, who began his career as a pioneer of stop-motion animation, was the director of the first Russian film to be shot entirely in color (The Stone Flower, 1946), and became famous for his eye-popping fantasy films which employed a variety of creative visual effects, including The New Gulliver (1935), Sadko (1952), Ilya Muromets (1956), Sampo (1959), The Tale of Tsar Saltan (1966), and Ruslan and Ludmila (1972). Though some of these films were hacked to pieces by Roger Corman and others in the 1960’s, badly dubbed and rendered incoherent (and thus making their way to Mystery Science Theater 3000), even in these bastardized versions Ptushko’s fertile imagination shines through. His touch is invaluable to Viy. The fantasy sequences have wit and a kind of comic-strip elegance. It’s a Russian ghost story filtered through the mind of a child, and as vivid.

The witch (Nikolai Kutuzov) rides the terrified Khoma (Leonid Kuravlyov) through the sky.

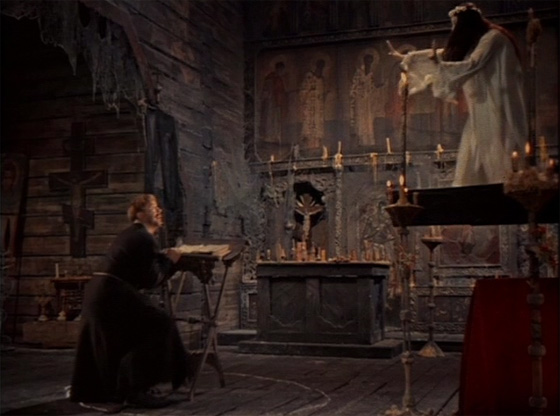

The simple narrative follows a student from the Kiev Seminary, Khoma Brutus (Leonid Kuravlyov), ending his studies for the summer and traveling with his friends through the countryside. An unfortunate decision to spend the night at one particular barn, which happens to be owned by a witch (so ugly she’s actually a man: Nikolai Kutuzov), leads to Khoma being trapped under a spell and guided through the night sky, the witch riding him like a horse. When they collapse back to Earth, the terrified Khoma beats the witch savagely…at which point she transforms into a beautiful young woman (Natalya Varley), who dies with tears on her cheeks. The matter isn’t over: he’s soon summoned to a village where a young girl has died; her dying wish was for none other than Khoma Brutus to spend three nights by her body praying for the salvation of her soul. He tells the grieving father that he never met the girl, but it’s a half-truth, for the body lying upon the bed is clearly that same girl whose likeness the witch took. The father tells Khoma that he will reward him handsomely if he obeys the girl’s instructions, and so the seminary student follows her corpse as it’s delivered in an open casket into an old church. It’s a spooky place, with creepy religious portraits and a door that resembles a standing coffin. After he lights candles, an invisible being blows them out. Less than sober, he stands at a podium and begins reciting prayers, and the girl’s body rises like a vampire from the casket. She gropes blindly toward Khoma, and in terror he draws a protective circle on the floorboards in white chalk. She presses her hands and leans against the invisible barrier. Thwarted, she returns to her coffin, and the lid lifts and slams shut on its own accord. Khoma’s efforts to escape the next day are thwarted, so he decides to get more drunk instead.

The witch (Natalya Varley) assaults Khoma's magic circle, riding a flying coffin.

On the second night, Khoma drunkenly slams down his prayer book and opens it, and a bird flies out, settling up in the rafters. He begins reading, and the witch rises once more. This time she flies through the air, riding her coffin like a surfboard, but even as she slams it again and again upon the barrier of Khoma’s magic circle, she can’t reach him. The cock’s crow interrupts her efforts. Now Khoma is desperate to escape, but neither the wealthy father nor the men of the village will allow him to leave, so he takes to more drink. The third night is a phantasmagoria of Ptushko’s creative effects work: the witch summons devils which at first are giant gray hands that come reaching out from the walls and the floor. Then winged gargoyles and deformed bat-men begin flooding the room, climbing down the walls and clawing through the cobwebs. Finally the witch summons a creature called “Viy,” a troll-like behemoth whose heavy eyelids need to be lifted by the devils. Once its gaze settles upon Khoma, they are able to penetrate his circle and swarm him. The cock crows and the witch and her demons are destroyed by the dawn, but by now Khoma is dead.

The witch summons her grotesque devils to attack Khoma.

Viy‘s reputation has grown in the ensuing decades as horror buffs have gradually discovered it (often comparing it to The Evil Dead); but it’s just as appealing for its clever visual effects as it is the folkloric style of storytelling – it would pair well with the “Fearnot” episode of Jim Henson’s The Storyteller (1988) or the Faerie Tale Theatre episode “The Boy Who Left Home to Find Out About the Shivers” (with the one-time-only cast of Peter MacNicol, Vincent Price, Christopher Lee, David Warner, and Frank Zappa). I watched the film this past Halloween while receiving trick-or-treaters, and it felt seasonally appropriate. Viy has an appealingly timeless veneer; unlike any film from America or Western Europe in 1967, you couldn’t guess the year Viy was made. And though it’s probably overlong at 78 minutes, the padding to the story is assisted by dollops of humor and persistently fantastique imagery: such as a drunken night at an inn, with Khoma hallucinating the same man emerging from three different doors simultaneously and in the same shot. The film is as restlessly creative and visually entertaining as any modern film by a Terry Gilliam or a Jean-Pierre Jeunet, but then again, I can hardly resist a film which features both a walking skeleton and a skeleton hydra.