In my review of The Warrior and the Sorceress (1984), I pointed out that it may be a lousy movie, but there is still a substantial divide between this low-budget exploitation movie from the Roger Corman factory and much of the straight-to-Netflix, zero-budgeted B-movies of today. At least it had a budget. It had costumes, actors, sets. In the same fantasy subgenre, you can see the contrast even more clearly when comparing Albert Pyun’s The Sword and the Sorcerer (1982) with his long-delayed follow-up, Tales of an Ancient Empire (2010). The former is a respectable B-picture, which has earned a cult following over the decades, largely from those who saw it as children or teenagers and magnified its virtues in their memories. The latter film – foretold by the ending credits with a Buckaroo Banzai Against the World Crime League-level optimism – is typical of modern Z-budget filmmaking, with an amateurish script, a cast made up largely of non-professionals (with the exception of poor Kevin Sorbo, who deserves better), and sloppy computer effects, some of which resemble the cut-scenes from a 1998 Playstation video game. Those FX fail to disguise the fact that most of the scenes appear to have been shot in Pyun’s basement. It’s the best of times, it’s the worst of times. The good news is that anyone can make a movie now, and the bad news is exactly that. To make a movie worth watching, talent is necessary, but sometimes money is too. If your script is akin to My Dinner with Andre or Gerry, you probably don’t require a million dollars to make your film. But if you’re going to film an epic fantasy about an army of vampires infesting a kingdom, you can’t count on cheaply-bought CGI to save the picture. The Sword and the Sorcerer, therefore, is not the cream of the crop of 80’s fantasy filmmaking, but by contrast to many of today’s efforts, it’s Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Alana (Kathleen Beller) negotiates for the services of rakish swordsman Talon (Lee Horsley).

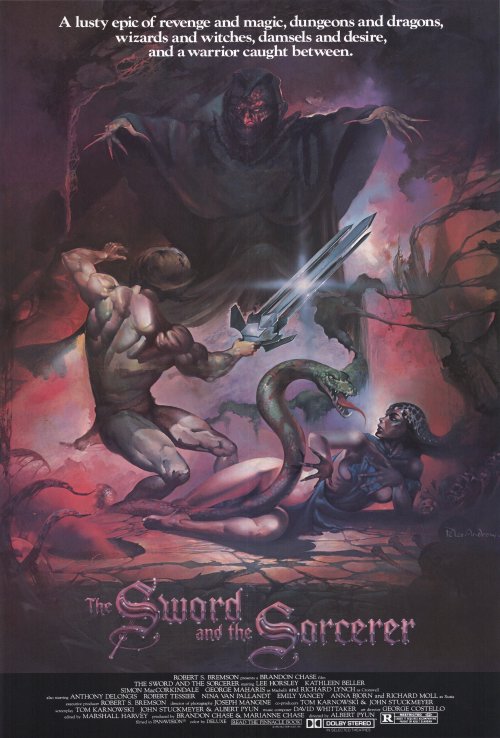

Actually, Raiders is clearly the strongest influence on Pyun for his film, which was released a year after Spielberg’s. Unlike the comparatively somber Excalibur (1981), Dragonslayer (1981), and Conan the Barbarian (1982), emphasis is placed on swashbuckling adventure and humor. It was – and still is – refreshing, vaguely reminiscent of the beloved Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser stories of Fritz Leiber. Lee Horsley stars as Talon, carrying a sword called the Triblade, which is what it sounds like: three parallel blades, two of which can be projectile-launched at the enemy. (Frankly, I would prefer to wield the Glaive from Krull rather than the awkward-looking Triblade, but I’m sure it has its fans.) As we learn during the opening scenes, Talon is actually the son of King Richard of Ehdan, who was murdered and usurped by the evil Cromwell (Richard Lynch). That’s not Oliver Cromwell, mind you; he’s a different one. One so evil that he conquers a kingdom with the black magic of a demonic sorcerer, then stabs that sorcerer and throws him from a cliff. With Talon in exile, the closest legitimate heir to the throne is Lord Mikah (Simon MacCorkindale), the son of King Richard’s closest adviser. When Mikah is arrested and thrown into the dungeons, his sister, Princess Alana (Kathleen Beller), hires Talon to rescue him. He agrees, for a price – one night in bed with the princess. But his apathy toward who controls the kingdom of Ehdan gradually erodes, until he’s leading a rebellion on Mikah’s behalf. Meanwhile, the betrayed sorcerer plots revenge against Cromwell, and to take Ehdan for himself.

Talon is crucified in the middle of King Cromwell's wedding to Alana.

The cliché-riddled narration of the opening scenes, establishing The Sword and the Sorcerer‘s elaborate backstory, quickly sets the tone of the film: old-fashioned and tongue-in-cheek. The score, by David Whitaker (Vampire Circus), follows suit, though it’s so persistently triumphant that it has a tendency to become cloying. I would have liked a few adventures in this here adventure film – maybe a monster or two, apart from the makeup-masked sorcerer – but although the plot gradually loses its momentum, the humor is deployed well, notably in the sexual bargaining between Talon and Alana in a tavern (with a touch of bawdy physical humor), and the droll cut between Talon’s Merry Men heroically announcing their attentions to raid the castle and their immediate imprisonment. Also memorable is Talon’s swordfighting Errol Flynn-style from one room of the palace to another, and his sudden emergence into a harem of topless slave-girls – one of whom he pauses to deeply kiss before resuming battle. In moments like these, Pyun finds himself on the right track: a nostalgic fantasy adventure for adults. Touches of gore and kink don’t hurt. So stick with the original, and pretend its sequel remained forever in the “what if” file, along with Buckaroo Banzai’s never-to-be-glimpsed World Crime League.

Note to 80’s TV fans: Richard Moll (Night Court) and Joe Regalbuto (Murphy Brown) are both prominently featured. For what it’s worth.