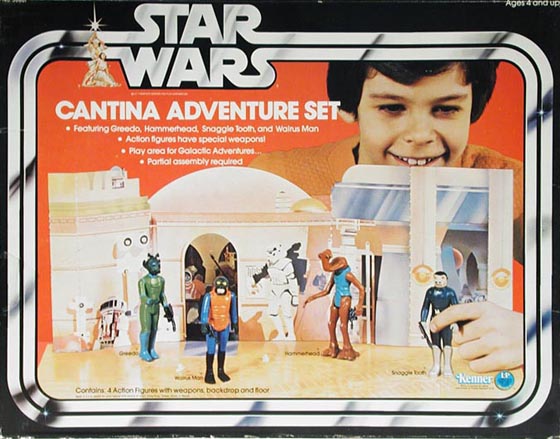

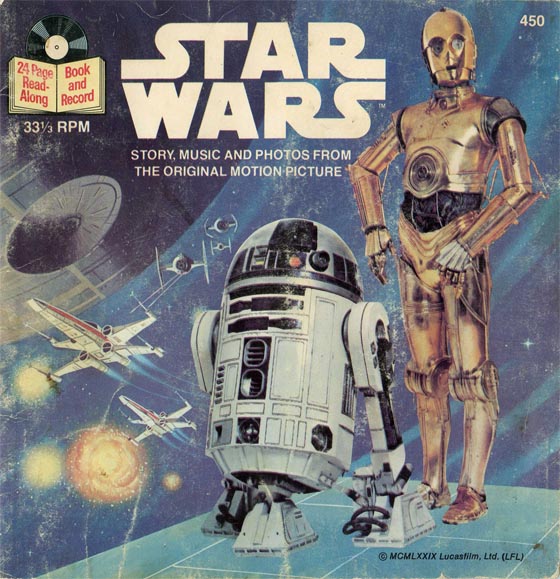

As a child, I slept in Star Wars sheets while wearing Star Wars pajamas. I listened to the storybook record and tapes of the radio adaptation. I collected the trading cards and obsessed over the action figures, setting a personal goal of collecting every monster who appeared in the Mos Eisley cantina; and I swooned with jealousy at those friends whose parents were rich enough to buy them the larger Star Wars sets, such as the Millenium Falcon and Death Star. I was horrified when my sister used my Luke Skywalker figure for the guillotine diorama she’d made for a class, leaving Luke’s severed head lying in a tiny basket. By the time Return of the Jedi was released, my collection was quite large. By now I had a Scholastic picture storybook acquired from a “Bookmobile” at school, bearing the redacted title Revenge of the Jedi. When I got the Return of the Jedi Sketchbook, I studied its concept art so intensely that it might as well have been holy scripture. I had the Ewok Village and Jabba’s throne room, with its pop-up trap door; I watched the Droids and Ewoks cartoons on TV, and had the Ewok TV-movies on tape, which I watched with my stuffed Wicket the Ewok in my arms. The Star Wars films weren’t really movies to me. They were something vaster: a gateway to a world I happily lived inside, because it was inherently more interesting to me than the drab suburbs of Union City, California. But at some point I moved past Star Wars, and let Tatooine, Yavin 4, Endor, and Hoth belong to my childhood. A couple decades later, when people my age were ranting and raving that Lucas had “raped” their childhoods with his prequels and “special editions” – and other such Jar Jar jibber-jabber – I felt completely disconnected; I had long since moved on and populated my imagination with other subjects. But I recently decided to purchase the Blu-Ray set and watch all six films in order of Lucas-stamped continuity; it had been more than a decade since I’d watched the original trilogy, so I wanted to see them fresh again.

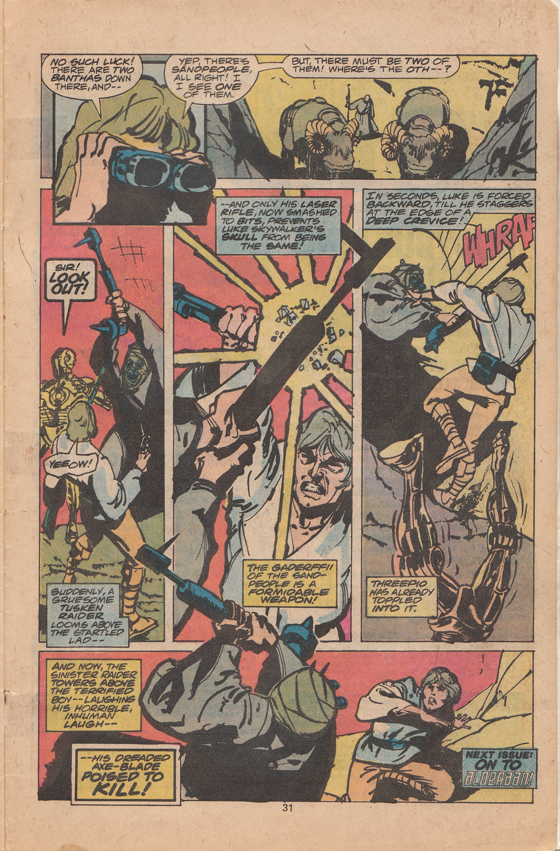

A page from Marvel Comics' "Star Wars" #1, written by Roy Thomas and illustrated by Howard Chaykin. Thomas, perhaps best known for his long run on Marvel's "Conan the Barbarian," states in the issue that he was hand-picked by Lucas to adapt the film.

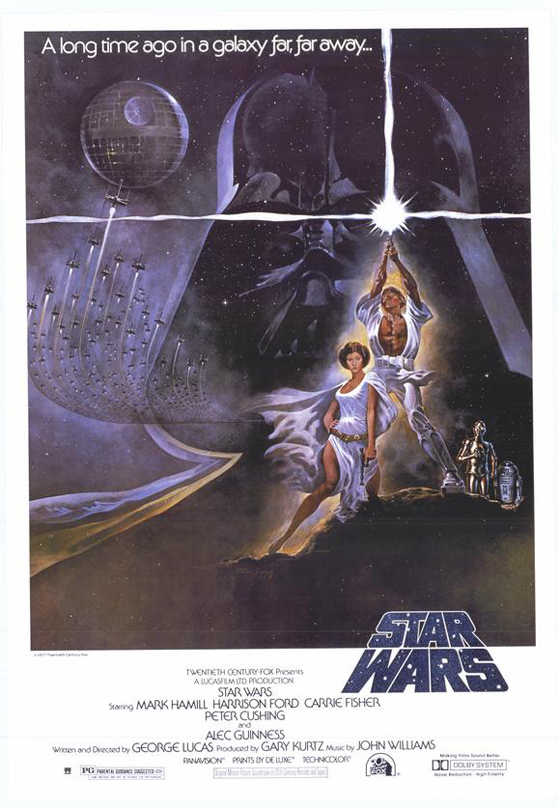

I will say this: it’s interesting to watch the films “in order,” but there is really nothing Lucas could have done to make a seamless transition from 2005 (III) to 1977 (IV). Star Wars was originally released without any “Episode IV: A New Hope” introducing the opening crawl. (I’m not here to add to the anti-Lucas rants, but the “special edition,” now unavoidable, really does apply sore-thumb CG onto its Tatooine sequences with garish abandon. I don’t understand all the complaining about Greedo shooting first, because the crudely-animated sequence of a 1977 Harrison Ford arguing with a 1997 Jabba the Hutt is more painfully distracting.) I am willing to take Lucas at his word that Star Wars was always meant to be part of a larger narrative, but it’s quite obvious that the story specifics of what would become the prequel trilogy were not yet in place. It feels like quibbling to complain that C-3PO ought to recognize Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru’s moisture farm, not to mention the planet Tatooine as a whole, since he was created there (readers, I’m asking you: is there a comic book or Star Wars novel out there which suggests that his memory bank was wiped?). And I’m sure you can write off Obi-Wan Kenobi’s mangled narrative of his Jedi Knight past by reading it as something of a white lie given to Luke to disguise more brutal truths, a reading more or less sanctioned starting with The Empire Strikes Back. When Obi-Wan tells the teenage Luke that he needs to learn the ways of the Force in order to go with him to Alderaan, it doesn’t even make sense in context of everything we’ve learned about the Jedi order in the previous three films. But all this is quibbling, because Star Wars is a film that was made in 1977 as an entirely self-contained fairy tale. Traveling from III to IV is going to be a jarring experience no matter what. The prequels are CG-heavy, state-of-the-art spectacles which belong to twenty-first century blockbuster moviemaking. In tone, content, and style they’re about as different from A New Hope as they are Barry Lyndon. Star Wars is scrappy, freewheeling, and fun. It’s considerably more innocent, and deliberately naïve.

The highly-prized "Cantina Adventure Set" was a Sears exclusive.

Although mention is made of the Clone Wars, Star Wars only really wants you to know a few basic things about its universe: there is a power called the Force; Darth Vader uses the Force for evil; and Obi-Wan Kenobi is an old Jedi Knight who is teaching Luke how to use the Force for good, to help the Rebel Alliance destroy Vader’s planet-destroying weapon, the Death Star. Everything surrounding that is simply nonsense which adds texture to the mythical world. When Luke says, “I used to bullseye womp rats in my T-16 back home,” you more or less know what Luke’s talking about, even though the movie isn’t stopping to explain to you what womp rats are, or even what a T-16 is. The actors complained about Lucas’ gobbledygook-laden script; they couldn’t yet see that the final product would look so convincing that it would help sell those lines. But this was fantasy world-building on the fly, limited by its budget and the effects of 1977, which meant that John Dykstra and the other wizards onboard would have to invent new technologies to bring battling X-Wings and TIE Fighters to life. Once the audience could see those ships soaring over the surface of the Death Star, it would be much easier to conceive of such concepts as the Clone Wars, and their own imaginations could eagerly fill in the rest of the details without the assistance of Ewan McGregor and Hayden Christensen.

The read-along storybook record.

So Star Wars, in retrospect, ironically seems like a modest production. Compared to its sequels and prequels, it’s somewhat lacking in complex storytelling, elaborate action scenes, or alien worlds (mainly serving up a lot of Tatooine, since the Tunisian desert made for such a spectacular and cheap special effect). But it’s propelled by humor and charm, some of it supplied by its two droids – quickly establishing themselves as the Laurel and Hardy of the series – and the rest by its young cast: Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, and Carrie Fisher. The three heroes are at each other’s throats for most of the running time, only eventually – but organically – becoming devoted to one another, the most human thread which will develop through Episodes V and VI. This equally-weighted balance of character and spectacle is fundamentally what makes the original trilogy superior to the prequels, which lose that balance. (Lucas mentions in the commentary track of The Phantom Menace that he muted his actors’ line delivery to keep the tone in step with that of the original films, which actually severely misrepresents the enthusiastic performances given by Hamill, Ford, and Fisher). Star Wars is also boosted by Lucas’ skills with editing an action sequence. The final raid on the Death Star is still heart-pounding, even after you’ve watched it a hundred times and memorized every beat. Throughout the film, Lucas creates an irresistible kinetic energy that carries you from scene to scene. This skill of his is evident in the prequels, whatever you might think of them. (Rewatching the pod race and Darth Maul duel, I’m struck by how The Phantom Menace suddenly comes to life. As though learning from the success of those two sequences, Lucas plays to his own strengths by making II and III more action-packed; they’re more enjoyable films as a result.)

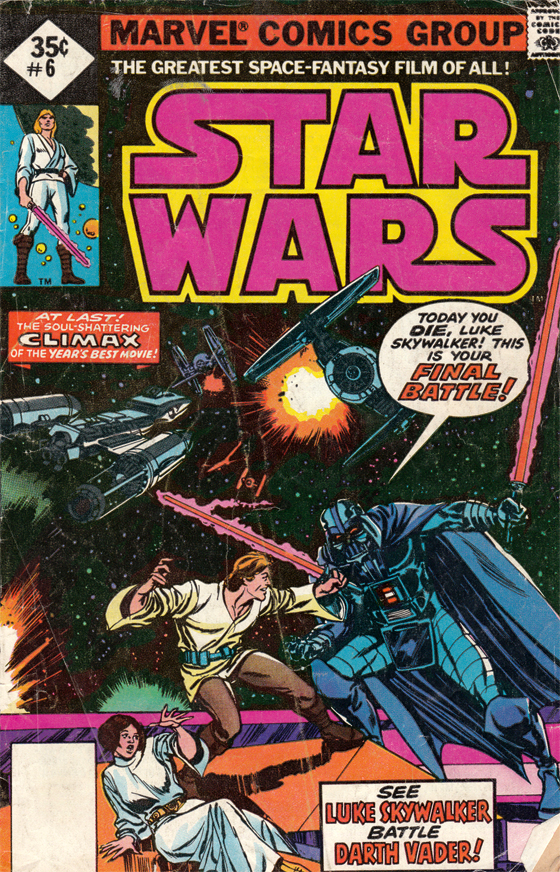

As an adult, I've long since abandoned my Star Wars collection of action figures and books, though I've kept my comic collection around. That extends to a few early issues of the Marvel Comics "Star Wars," including #6, with its misleading (but "soul-shattering") cover.

Lucas composes his films like a musician, which is why he met his perfect symbiotic match in John Williams, who, with Star Wars, returned film soundtracks to the world of the grandly symphonic. Their collaboration is a genuine artistic achievement, somewhat taken for granted over the decades, the result of the pop cultural impact-crater these films created. Williams finds some grand themes and varying leitmotifs to match the recurring ideas and characters which Lucas plays with in his serialized story, until, by the time their collaboration reached Revenge of the Sith, there are so many layers visually and aurally that it becomes a genuinely operatic experience, albeit a uniquely cinematic one. (If you are tracking the story through its music, you will find this to be the strongest argument to watch the films in the order they were actually made.) Look, all of these films are exquisitely crafted. I still find the various making-of documentaries engrossing, simply because of the level of detail given every minor character’s costume design. But rewatching Star Wars, I’m reminded that at one time the scale was a little smaller, the stakes lower. It was a simple escapist adventure story – a little bit Western, a little bit Kurosawa, a little bit rescue-the-princess fantasy – and we loved George Lucas for it. The Empire Strikes Back would be better in every way (I’d argue it’s a masterpiece), but it was also the start of an increasingly burdensome and convoluted mythology. Star Wars was just some funny banter, exciting thrills, chirping Jawas, spider-droids, lightsabers, Tusken Raiders, low-res holograms, clattering stormtroopers, and stop-motion-animated chess. Sometimes the glue and tape showed, but it was still enough imagination to sustain any child to adulthood.