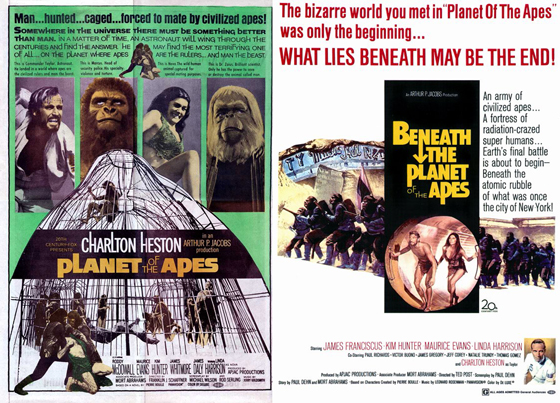

Has there ever been a more unexpected cinematic franchise than that spawned by Planet of the Apes (1968)? Actors in ape makeup, their moving lips unglimpsed beneath a coconut-shaped mouthpiece, arguing over matters of politics, science, and philosophy. Each film writes itself into a corner, but commercial demands require a sequel, and so the series resurrects itself – eventually forming, over the course of its five installments, a time-twisting Möbius strip. Then the obligatory remake. Then another prequel, with state-of-the-art CG effects – a film that became a surprising sleeper hit in 2011 (a sequel to the prequel has just been announced). Not to mention a live-action television series, an animated series, and comic books from 70’s Gold Key and Marvel Comics to a current series by BOOM! Studios. I can understand why we are treated to a pile of new superhero films every summer; I can understand why we keep revisiting Sherlock Holmes and Dracula; I can wrap my head around why the Twilight series was a big hit. Planet of the Apes, a ubiquitous pop culture presence in the 70’s, is more difficult to fathom. It ought to have been a flop. The whole thing ought to have been a tremendous disaster. But although there’s a certain camp appreciation for the original film, there’s also a heap of unironic love. The film is regarded as a science fiction classic; and, indeed, how many genuinely thoughtful films in that genre do we receive on a yearly basis? In retrospect, it was the beginning of a minor golden age for cinematic science fiction. 2001: A Space Odyssey would be released only two months after Planet of the Apes. We’d soon get the likes of Silent Running (1972) and Soylent Green (1973). It was okay to attend a science fiction film with your brain screwed on tight.

Stranded astronaut Taylor (Charlton Heston) takes Dr. Zaius (Maurice Evans) hostage in "Planet of the Apes."

The franchise’s longevity is also strange when you consider what a delicate balance the first Planet of the Apes wields. It’s an ideas-driven science fiction film, an action picture, an escape-from-prison thriller, and a broad satire. The apes are, at first, horrific – when Taylor (Charlton Heston) and his fellow astronauts crash on what they presume is a distant planet, they’re hunted by mounted warriors with gorilla faces, and rounded up into cages with other humans who are apparently mute and savage; some of those human victims, killed in the hunt, are strung up by their ankles like dead rabbits ready to be skinned. A moment later, we see the gorilla soldiers posing in front of a pile of dead men. “Smile,” says an ape behind a camera, and he snaps a picture: black comedy, with overtones of the horrors of Vietnam. Other jokes are corny (“All men look alike to most apes!”). Some cross into the sublime, like a famous, unscripted moment during Taylor’s trial, when the three obstinate orangutan judges strike a “See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil” pose. And there’s talking – lots and lots of talking. As much as its notorious twist ending (provided by co-screenwriter Rod Serling), Planet of the Apes is borne on the back of its debates over the roles of science and religion in a developing civilization, and the value of questioning one’s origins. It’s the Scopes Monkey Trial with real monkeys. There are also, of course, questions raised about experimentation on animals – the animals, in the film’s classic reversal, being humans. Rise of the Planet of the Apes took on the same theme, but it’s easy to forget that the 1968 film treated it with such originality by placing Charlton Heston in a cage surrounded by primitive humans abused by their simian scientists. The thrust of the narrative is Taylor proving to his captors that he’s more than a beast, while the elite of the society hide behind legalese and religious doctrine to avoid what should be a very obvious conclusion.

Scientists Zira (Kim Hunter) and Cornelius (Roddy McDowall) help Taylor escape to the Forbidden Zone.

The film was adapted by Serling from the 1963 novel La Planète des singes by Pierre Boulle, and rewritten by Michael Wilson, Oscar-winner for his screenplay (with Harry Brown) for A Place in the Sun (1951), and formerly blacklisted by HUAC, this being one of his comeback films after returning to the United States in 1964. The strength of the script is the film’s ace in the hole, but it’s helped considerably by the performances – under heavy makeup – by Kim Hunter (A Matter of Life and Death, A Streetcar Named Desire), Maurice Evans (Rosemary’s Baby), and, of course, the great Roddy McDowall, here moving about the sets with an appropriate chimpanzee hop. Charlton Heston delivers most of his lines through gritted teeth, and those lines have been oft-quoted over the decades. Despite the G-rating, he’s occasionally nude and never gets to wear much more than a loincloth for most of the film. In his manliest moment, he kisses Kim Hunter right on her simian lips. An eerie, borderline avant-garde score by Jerry Goldsmith has become a classic of its kind, capturing the story’s savagery and otherworldliness. Director Franklin J. Schaffner used the film’s success to graduate to prestige projects like Patton (1970) and Papillon (1973).

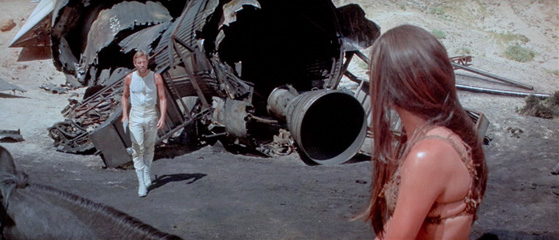

Brent (James Franciscus) meets Nova (Linda Harrison) and embarks on a search for the missing Taylor in "Beneath the Planet of the Apes."

The film’s ending is pretty definitive, and about as famous as that of Psycho or The Sixth Sense, to the extent that it was even spoiled on the cover of the film’s DVD release. (Heeding fan complaints, Twentieth Century Fox chose a different design for the Blu-Ray cover.) Because it’s impossible to discuss the sequel without spoiling the original film, I’m assuming you’re familiar with it, so let’s press on: Beneath the Planet of the Apes (1970) picks up directly from the previous adventure, with Taylor and his companion, the beautiful but mute Nova (Linda Harrison), leaving the remnants of the Statue of Liberty behind to explore deeper into the “Forbidden Zone,” that region of the planet where the apes fear to tread. They encounter a spontaneous wall of flame, bolts of lightning, and fissures which suddenly open in the earth – all of them pretty cheap special effects which should indicate to the viewer that a smaller budget has been applied to this sequel. Then Taylor vanishes through a wall of rock, and Nova is left alone – eventually encountering Brent (James Franciscus, The Valley of Gwangi), an astronaut conveniently arrived on the Planet of the Apes on a second ship closely following Taylor’s. The two journey to the ape city, where they glimpse an army of gorilla troops preparing to venture into the Forbidden Zone, and meet up with Zira (Hunter) and Cornelius (now played by David Watson, somewhat imitating McDowall’s mannerisms). This stop only briefly delays us from the main plot, which is an adventure deeper into the ruins of New York City. Brent and Nova travel through more landmarks like the subway system and the New York Stock Exchange before encountering a tribe of telepathic humans holding Taylor captive, and worshiping an unexploded bomb which has the capability of destroying the world.

Gold Key's adaptation of "Beneath the Planet of the Apes" was the first of a long line of Apes-franchise comic books.

Not only is the budget more modest, but – to its great detriment – so is everything else: Beneath the Planet of the Apes is a B-movie answer to the original’s A-lister, spending less time on the apes and their philosophical torment, and more on Nova’s One Million Years B.C. cavegirl glamor and the villainous doomsday cult, which seems to be inspired by horror movies, pulpy serials, and maybe just a bit of The Prisoner. The ideas put forth are simpler, as well; there’s less here on evolutionary biology than you’d expect, as the film, from Paul Dehn’s script, focuses instead on the notion that man was only replaced by apes because he destroyed himself – devolution spurred by nuclear war. Here we see hippie chimps campus-protesting against the militaristic gorillas. But the story seems rooted in fears older than the riots of ’68 – nuclear apocalypse hangs as heavy over Beneath the Planet of the Apes as any atom-age thriller from the “duck and cover” years. This is a film about the end of the world, period, and you can’t miss it, particularly when it’s Chuck Heston himself throwing the switch on the bomb at the film’s cataclysmic finale, leading us to blackness and a narrator informing us that “a green and insignificant planet is now dead.” The actor – whose role is little more than an extended cameo – insisted upon this ending. He was hoping this would be the last Planet of the Apes film, but he underestimated those apes, as well as the elastic ingenuity of science fiction…