The opening titles proclaim this to be “Thomas De Quincey’s classic Confessions of an Opium Eater.” Make no mistake, this has nothing to do with the landmark account of drug addiction from 1821 (Confessions of an English Opium-Eater); and, perhaps by excuse, the lead character is called Gilbert De Quincey. No, this is a low budget exploitation picture from 1962 – alternate title, Souls for Sale – with one foot in the Roger Corman AIP films of the era, and another in politically-incorrect pulp fiction from decades past: the sort populated by Chinese gangsters and dragon ladies. There is some opium-eating, but not much. One can imagine the quick discussion at Allied Artists. What’s a title people recognize that won’t cost a dime in rights? Good; has anyone actually read that book? No? Perfect! At the helm was Albert Zugsmith, director of College Confidential (1960), in which Steve Allen is accused of corrupting college students with his unseemly interest in the topic of sex. The screenplay was by Robert Hill, who had worked with Zugsmith on the Mamie Van Doren vehicles The Private Lives of Adam and Eve (1960, with Mickey Rooney) and Sex Kittens Go to College (1960). Vincent Price, between The Pit and the Pendulum (1961) and Tales of Terror (1962), was tapped to play Gilbert.

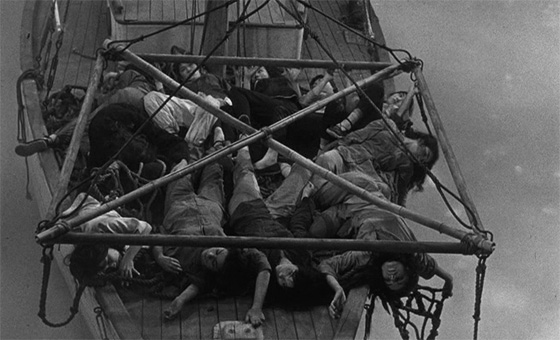

Human cargo is dumped violently into a boat in the film's surreal opening.

I would say that Price is miscast, but that would presume I had an inkling of what the filmmakers were aiming for. Gilbert De Quincey is a tough man-for-hire in the film noir vein, who, following some suggested adventures in China (the film introduces him as though he’s a character in an ongoing series that we’ve never heard of), arrives in San Francisco’s Chinatown looking for a new job. He’s hired by an unseen gang boss – via the film’s requisite dragon lady, Ruby Low (Linda Ho) – to infiltrate the rival Tongs following the death of a Tong leader, the editor of the Chinatown Gazette. At least, that’s about as much as I can make out through the dialogue, an almost impenetrable mix of calculatedly broken English, overwrought hard-boiled narration, and failed stabs at poetry. When De Quincey first encounters Ruby Low, Price passionately recites a delirious voiceover: “There is a devil in the drunkard and a ghost in the poet. Devil and drunkard, ghost and poet was I. But once to every man there comes a premonition of destiny. In that first instant of her image passing the lenses of my eyes, I felt that I was hanging in the immensity of space, and she was floating with me, chained, locked inextricably together, arms, brains, heart pulsations, unable to flee, unable to break apart, sinking, sinking through the inexhaustible depths of time. I forgot the long journey by the sea. I forgot the pain, I forgot my mission. Was it the heavy, drifting perfume of the incense, or some feverish fantasy searing my brain? Whatever it was, as I looked at her for a heartbeat, I knew, whoever she was, whatever she might be, this woman had to be a kind of…fate, for me.” While Ruby Low lights a funerary candle, Price takes her match and puts it to his cigarette. She scowls and says, “I am not sing-song girl to light cigarette!” He replies, “Sorry, I got carried away.”

Gilbert De Quincey (Vincent Price) descends below Chinatown to investigate human trafficking.

The style of the film is a bizarre mix of Fu Manchu clichés and quasi-psychedelic surrealism. Price is constantly finding secret, sliding doors and hidden passages and elevators, descending deeper into Chinatown. He passes through one door and finds a bathhouse. Another door – behind a bathroom stall – and he finds an opium den, where he smokes a pipe and hallucinates spook-show images. Another and he encounters women in bamboo prisons, including an unexpected ally in a courtesan dwarf whom he mistakes for a child, even though she’s played by Yvonne Moray, born in 1917 and a cast member from The Wizard of Oz. (The moment when he touches her middle-aged face and announces, “You’re no child!” is just part and parcel with the film’s nonstop weirdness.) Zugsmith sometimes slows the action, speeds it up, reverses it, or even removes the soundtrack and lets silence dominate. Much of this is for effect, but sometimes it’s just to disguise the film’s limited resources, such as the awkward moment when Chinese prostitutes are dumped onto the deck of a boat. A staccato series of images is edited together to give the impression that they’ve been violently dropped from the suspended net, when in actuality they are carefully posed from one frame to the next. Brief shots like these can seem accidentally avant-garde. The same goes for the film’s final scene, as two of the Chinese fugitives watch Price drifting downstream through an underground canal. In one of the shots we see them moving in reverse. Presumably in the editing room it was discovered they needed a few more beats. But the result just adds to the film’s strange atmosphere.

Yvonne Moray helps Price sabotage the Tong conspiracy.

Chinatown, here, is a Western set hastily dressed with Chinese signs, and Price crashes in slow-motion through a balcony as though he’s part of a Wild West stunt show. The soundtrack, by the prolific B-movie composer Albert Glasser, is often dominated by theremin, which is always a plus. The odd moments are countless. A fake seagull drops from the sky to land at Price’s feet. There’s a villain talking from behind a bearded porcelain mask, battles with axes and swords, and an extended scene involving “exotic” dancing girls, one of whom has her wig suddenly removed to reveal her baldness (or obvious bald cap, anyway) – “She has no hair!” one of the men screams, and she’s chased off. It is a strange, strange little film, and one that in recent years has gained a reputation thanks to the Psychotronic Film Guide, occasional screenings on Turner Classic Movies, and Joe Dante’s enthusiastic endorsement on Trailers from Hell. The Warner Archive’s recent DVD release is therefore most welcome. Mind you: the movie is a disaster, ill-conceived, hastily produced. But its appeal lies in its genre mash-up script, its confused attempts at profundity, and Price’s always-game performance (when an expression of embarrassment might be more appropriate). Don’t watch it during the light of day and reason.