I have wanted to see Harry Kümel’s Malpertuis (1972) ever since reading a detailed synopsis in Phil Hardy’s Horror: The Aurum Film Encyclopedia (1985; indispensable for its many obscure films, less commendable for its often patronizing opinions of the genre). Hardy described a film in which Orson Welles captures the Greek gods and uses a taxidermist to sew them into human skins and transform them into “petit bourgeois characters in a large old house in Ghent.” Sold! But for years I could not find the film anywhere, and – with that title – constantly forgot what it was called unless I had Hardy’s reference book handy. Thankfully, the film has been released on a region-free Belgian DVD set which includes two versions of the film: the 100 minute Cannes cut available in French or English dubs, and the post-Cannes “director’s cut” of 119 minutes in the original Dutch. (I watched the director’s cut for this review.) Kümel is the Belgian director of the vampire film Daughters of Darkness (Les lèvres rouges, 1971), and Malpertuis was his ambitious follow-up, a big-budget adaptation of a novel by Jean Ray first published in 1943. Mathieu Carrière (Young Torless) stars as Jan, a sailor whose ship is docked for one night in his hometown of Ghent, in Flemish Belgium. He shows a strange reluctance to stepping off the ship, as if aware of the trap that awaits him – a trap of familial obligations and the estate of Malpertuis, overseen by his uncle Cassavius (Welles). After a brawl at an erotic-themed nightclub called the Venus Bar, he awakens in Malpertuis under the loving care of his sister, Nancy (Susan Hampshire, Those Daring Young Men in Their Jaunty Jalopies). Malpertuis is a vast house with mysteries lurking in its attic and its basement, and surreal shots of stairwells indicate the place may be dozens of stories deep. The staff spends each day bickering with one another in the drawing room, involved in their own melodramas. Cassavius is in his final days, and he gathers everyone around his bed to deliver his bizarre will: when there are only two people left alive in Malpertuis, they must wed and inherit the estate. Until then, no one may leave. He is left alone with the beautiful Euryale (Hampshire, again) and asks to look into her eyes. Later, his coffin is so heavy that the funeral procession accidentally drops it down the stairs. Only later, when Jan opens the coffin, does he discover that Cassavius has turned to stone.

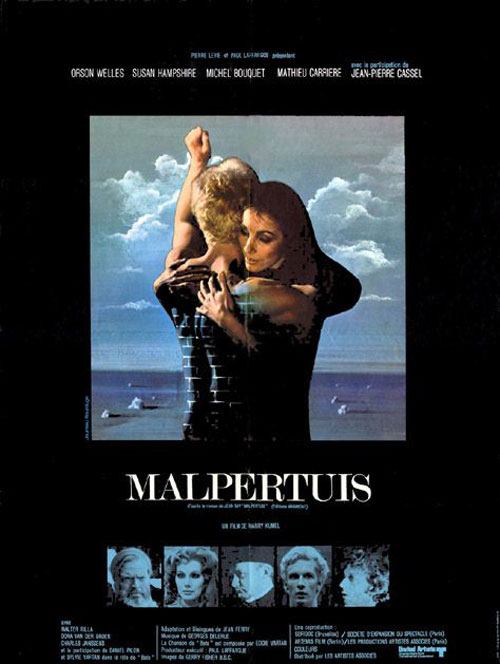

Jan (Mathieu Carrière) attempts to court Euryale (Susan Hampshire), one of those trapped in Malpertuis.

The film, released in the U.S. as The Legend of Doom House, has elements of horror, including the Gothic decor of Malpertuis, and the taxidermist (Charles Janssens) who keeps his own Frankenstein lab filled with jars of mutated homunculi, and locks Jan to an operating table with manacles, threatening to dissect him. The servants, of course, are Greek gods, whom Cassavius found on a sea voyage and trapped in his home; all of them anxiously await his death so they can revolt. When they do, Kümel treats them like zombies, staggering slowly and moaning (though Vulcan suddenly lunges forward and breathes fire). But Malpertuis is not a horror film; it’s a surreal art-house fantasy in the lineage of Jean Cocteau’s films, and at times reminiscent – in style and tone – of Welles’ The Trial (1962) and Wojciech Has’ The Hourglass Sanatorium (1973). (If compared to a genre film, the closest equivalent might be Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil, 1972.) Certainly it’s a difficult film that gets better as it goes along – and probably improves on subsequent viewings, since so many of its mysteries go unanswered until the end. Hampshire gives a standout performance in multiple roles: she not only plays Jan’s sister and the gorgon Euryale, but also the lustful Alice, whose deep longing to be human has made her forget that she is truly Alecto, the Greek Fury of vengeance. (She spends her days knitting with her two sisters, in one of the film’s many clever interpretations of Greek mythology.)

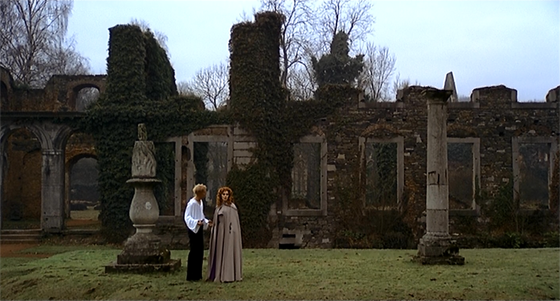

Jan explores the many levels – and realities – of Malpertuis.

One of the film’s more intriguing aspects is that the presence of the gods seems to have warped all reality around Malpertuis, creating an alternate dimension. The film explicitly references Lewis Carroll in its opening and closing credits (the opening titles display the John Tenniel drawing of the Jabberwocky), and present the house of Cassavius as a kind of Wonderland that can only be approached through dreams or other indirect means. Cassavius himself proclaims that he has mastered “eternity.” The infinite stairwells that stretch up and down the house seem to parallel the immortality of its inhabitants – we learn that even Cassavius may have personally known Cagliostro, the 18th century occultist – and the Möbius strip structure of the film implies Jan’s own eternal imprisonment in the house. At the film’s best, it piles on the fantastic images with quick edits, strange camera angles, decrepit set dressings, and intriguing allusions to mythology, so that it overwhelms. If anything, the film could have used more of this; it works better in its final half hour, when Kümel piles on the weird while simultaneously revealing the meaning of what has come before. (Oddly, the film is better once Welles leaves it. His presence may be a selling point, but the bedridden character only slows the film’s manic imagination.) Despite its flaws, the achievement of Malpertuis is its depiction of a unique microcosm: a house corrupted by imprisoned magic, where time, space, and memory lose their traditional meaning.