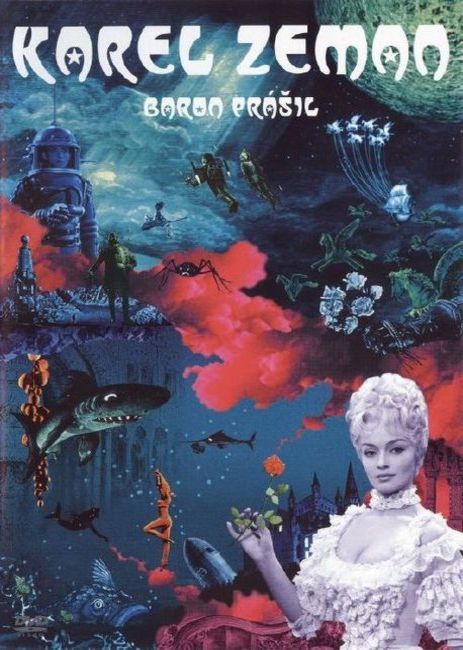

Baron Prášil (1961), or The Fabulous Baron Munchausen, was the fourth feature film by Czech animator/director Karel Zeman, following his dazzling The Fabulous World of Jules Verne (Vynález zkázy, 1958) and building upon its intricate and delightful production design. Here we see his unique style approaching perfection. Certainly the subject matter is ideal for his surrealistic approach. The tall-tale exploits of Baron Munchausen (in reality, German nobleman Hieronymus Carl Friedrich Baron von Münchhausen) gained wide popularity with the 18th century books, by Rudolf Erich Raspe and Gottfried August Bürger, purporting to tell of the Baron’s adventures across the world, under the sea, and on the Moon. A later volume illustrated by Gustave Doré has become iconic of both the great illustrator’s work and the Baron himself. The antiquated fantasy world of Munchausen is a natural landscape for Zeman, whose films combine live action with a variety of styles of animation, most prominently paper cut-outs. Truly, Zeman’s encounter with the Baron was inevitable: where The Fabulous World of Jules Verne strove to replicate the 19th century illustrations of Verne novels, The Fabulous Baron Munchausen would apply the same techniques to bring to life the Munchausen of Doré.

Baron Munchausen returns from the Moon on a ship borne by winged horses.

The opening is sublime. Following a primal thunderstorm, Zeman’s camera tracks footprints through the sand while Zdenek Liska’s score thumps along like an invisible traveler. We stop to scrutinize a toad squatting upon a toppled jug in a pool of water – another clue of human civilization – before Zeman pans up to stop-motion butterflies fluttering through the air. He pans up again: a man on a Wright Brothers-style aircraft glides past. Up again: a flock of stop-motion geese. Further up, while Liska’s strings rise dramatically: a sputtering biplane. Further up: eagles, and then jet airplanes. Finally, breathlessly, we are in outer space, and a buzzing rocket zips by, leaving Earth’s orbit for the Moon. Then we’re on the Moon’s surface, tracking more footprints in the lunar dust. An astronaut leaves his spacecraft, and he looks down. Those aren’t his footprints…whose are they? (Consider that this inspired opening anticipates by years not just Ray Harryhausen’s First Men in the Moon, but the eons-spanning jumpcut of 2001: A Space Odyssey.) The astronaut follows the path over a hill, and discovers a phonograph. He puts a needle to the record, and it plays. Walking a little further, he discovers the rocket from Verne’s 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon; we know this, because the plaque on the rocket gives the title and year – and also because its three pilots are standing only a few yards away to greet him. Then out comes Cyrano de Bergerac (who wrote a 17th century novel about his trip to the Moon). Of course, Baron Munchausen himself is there (played by Milos Kopecký), who mistakes the spacesuited astronaut as a creature native to the Moon. He offers to show the Moon Man, whose real name is Tony (Rudolf Jelínek), what the Earth is like – or at least the Earth as the Baron knows it. And so they embark on a galleon pulled by winged horses. The Baron first takes Tony to see the Turks, because he thinks all the crescent moons will remind him of home.

An ornate mise-en-scène, with a chase scene framed by the symbolic images of the Moon and a rose.

At the palace of the Great Sultan, Tony falls for the Princess Bianca (Jana Brejchová), who flees with them while the Sultan sends his army in pursuit. We follow the Baron’s new adventures as he finds himself in the midst of a naval battle, in the belly of a giant fish, in the claws of a great bird, and finally inside a besieged castle, where he takes his famous cannonball ride. But this is a film in which the details are more important than the plot. Telling a fantasy (of “lies”) rather than a science fiction story of Verne’s, Zeman is free to unleash his animator’s imagination on the screen. The visual gags come at a breathless pace. When Tony approaches the Sultan’s throne, spears come thrusting forward; only on experimentation does he discover that the spears are triggered by a Rube Goldberg-style mechanism just under the throne (Zeman quickly pans down to reveal the machine-works below, seamlessly blending live action with animation). After some fighting that’s just as much about chess as it is swordplay, the Baron and Tony flee to a sealed chamber and throw themselves against the doors, which resist all their efforts; then Bianca casually reveals that they’re sliding doors, which happen to be unlocked. On and on it goes, full of visual invention, but driven by a central comedic premise: that the Baron always misinterprets and yet, somehow, is always proven to be true. Zeman shoots only a few scenes in color, preferring to tint his black-and-white in the style of silent cinema; but he frequently experiments, so that many shots look as though they’ve been dipped in various dyes. Nothing is ever visually dull, such as when the Baron, Tony, and the Princess are chased out of the Turkish city not just by the Turks, but by a billowing red cloud that stains the orange-tinted backdrop. Eventually, while the Baron narrates, the chase scene is poetically framed by the image of a rose touching the Moon – symbolic, as the Baron explains, of the Princess falling under the spell of Tony’s tales of the future. In Zeman’s intriguing retelling of the Munchausen story, the Baron finds Tony to be a rival fabulist: one whose tales of rocketships just happen to be true. (The Baron is dismayed that the Princess finds these tales of modern technology so enchanting, rather than the Baron’s fantasies. In one of the film’s most clever sequences, we see the Baron adrift on a raft with the Princess, surrounded by sea serpents and flying beasts – all things that are part of the Baron’s world and no one else’s.) Only at the end of the story does Tony arrive at a strategy worthy of the Baron: to use gunpowder to propel them back to the Moon inside a flying castle. The Baron is proud of such an unreasonable plan.

The Baron (Milos Kopecký) finds himself in the belly of a giant fish.

The modern viewer watching this film will inevitably be reminded of Terry Gilliam, and not just because he directed the most well-known Munchausen film, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988). Zeman’s style of animating cut-outs, as well as optically matting live action against drawings, bears an uncanny resemblance to the Gilliam animations of Monty Python’s Flying Circus some eight years later – as though what we know of the director fermented here, in the work of Karel Zeman. In particular, the extended sequence in the belly of the fish – in which the Baron and the Princess take refuge in the cabin of a swallowed ship – seems to have directly influenced the later film adaptation. In Ian Christie’s book Gilliam on Gilliam (1999), the former Python acknowledges the influence: “I think it was seeing a picture from Karel Zeman’s Munchausen in a Nation Film Theatre programme that got me excited. It seemed to be a combination of live action with drawn backgrounds, and somewhere along the line I got to see the film.” Gilliam also notes that he then saw the (interesting, but inferior) 1943 Münchhausen made in Germany under the Nazi regime. (The owner of the remake rights for this film filed a lawsuit during the production of Gilliam’s film, despite the fact that the books were in the public domain; the suit was later dropped.) “I didn’t like the German version particularly, but Munchausen was in the air. I read the book and in many ways it was the Doré illustrations that seduced me. This is what happened with Don Quixote* as well – it seems to be my mission in life to make Doré come alive.” Clearly he and Zeman were kindred spirits. In both films is the spirit of Doré’s illustrations, as well as a great deal of the mischievous Baron himself.

*See 2002’s documentary Lost in La Mancha for more on that Don Quixote business…