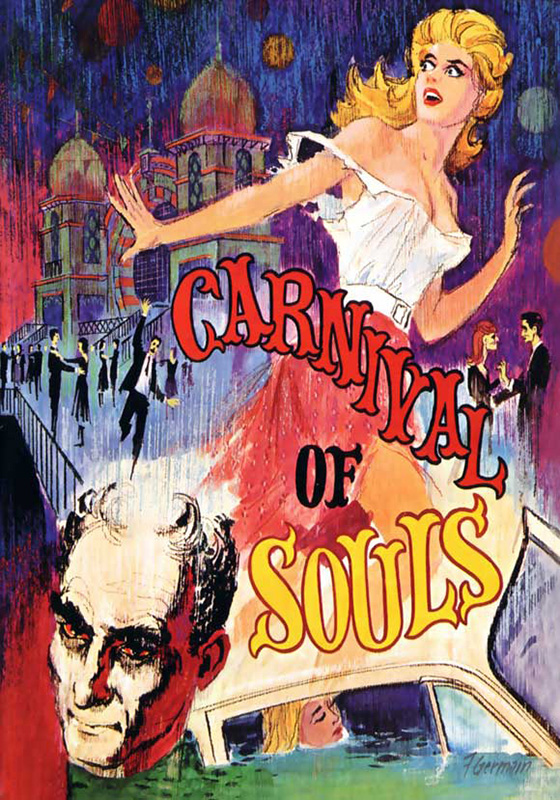

It’s increasingly rare that a horror film can strike out its own psychic space – if not free of the influence of other horror films, then at least original in unique and exciting ways. Carnival of Souls (1962) exists in its own particular netherworld. One might say that a film is like Carnival of Souls, but what is Carnival of Souls like? A bit of silent horror cinema, a few drops of European art film, a dash of “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge,” and a heaping spoonful of lucky accident. As you begin to watch the film, it feels like many other early 60’s drive-in pictures: a bit wobbly on its legs, the low budget and limited means of its production team quite evident. Your expectations are set accordingly. Maybe you’ll get some exploitation-level fun, something like a Tormented (1960) or The Screaming Skull (1958), but you’re certainly not expecting a masterpiece. After a drag race ends with a car careening off a bridge and into a river, young blonde organist Mary Henry (Candace Hilligoss, The Curse of the Living Corpse) is the only one who comes crawling out, her clothes draped in mud. Piecing her life together, she travels to Salt Lake City, takes an apartment with an overbearing landlady (Frances Feist) and a leering neighbor (Sidney Berger), and finds a position as a church organist, though she’s more interested in an opportunity to play music than to celebrate the Lord. The film has its own pace, and you wait for something to happen. Then, as she takes a nighttime drive outside city limits and to the abandoned Salt Lake resort called Saltair, a ghostly face looms out the passenger window, breaking the deliberately low-key atmosphere with supernatural foreboding and dread. The makeup is not a hokey monster mask but the bleached-white face of a corpse, and it’s eerie as hell. And the soundtrack of organ music bleats on: eventually it begins to sound less like church music and more like the strains of an old carnival.

Mary Henry (Candace Hilligoss) contends with strange visions in Salt Lake City.

Saltair looms and beckons. Mary drifts, disturbing her priest employer when her music takes on a more sinister quality, playing it like one possessed, and she’s fired. She even goes on a date with her creepy neighbor, as though desperate to prove that she can still engage with life through social obligations – and she creeps him out. There’s something very wrong about this girl. She seems to be sleepwalking through her new life, unable to figure out how she’s supposed to behave, what’s expected of her. She’s disconnected, and can’t pick up those societal rhythms she’d once had memorized. And just as the phantom figure keeps appearing, following her with wide, hungry eyes, she’s compelled into a parallel reality. She’s shopping in downtown SLC when suddenly no one can see her. The effect lasts only a short time, but she’s beginning to wonder. And in Saltair, the old abandoned carnival comes to life, and the ghosts rise out of the Salt Lake and waltz before giving chase.

Saltair, outside Salt Lake City, Utah, as seen in Carnival of Souls.

Sure, you can figure out what’s really going on, and I am sure many viewers in 1962 could as well; The Twilight Zone was in the middle of its influential run, and Carnival of Souls plays like a feature-length version, minus the Rod Serling bookends. But it works. It doesn’t take a big budget to make a disturbing, evocative horror film, and director Herk Harvey, who plays the central phantom and whose day job was creating industrial films, makes the most of his Salt Lake City locations. SLC has wide open streets, built to fit horse-drawn wagons, laid out in a square grid; even parts of downtown SLC look like small town, vanilla-flavored America, especially in 1962. Harvey makes the city look almost deserted, haunted, and when he heads to nearby Saltair, he finds his perfect haunted house. The Saltair Pavilion was a resort that was rebuilt multiple times and with various purposes: first as a Mormon getaway, then as a dance hall and a carnival, among other incarnations. It is still in use today as a music venue – alas, the old carnival rides on display in Carnival of Souls are no longer there. It’s Harvey who brings the old glory days of Saltair back to life, with lights and music and his cast of extras dunking themselves in the cold water at night. The real history of the location, and the fact that Harvey doesn’t try to disguise its identity for the big screen, gives the film a special quality: it’s like you are really seeing the ghosts of the past dancing before your eyes. Carnival of Souls anticipates Night of the Living Dead (1968) with its sooty-eyed undead lurching toward the blonde protagonist, but it also arrived at just the right time, capturing Saltair before another phase of its history vanished, and goosing the horror genre just when it needed it. There’s a cold dread under the small town banal of Carnival of Souls. Herk Harvey tuned into something vital for the genre, which so many of his contemporaries were missing, even those who had greater means.