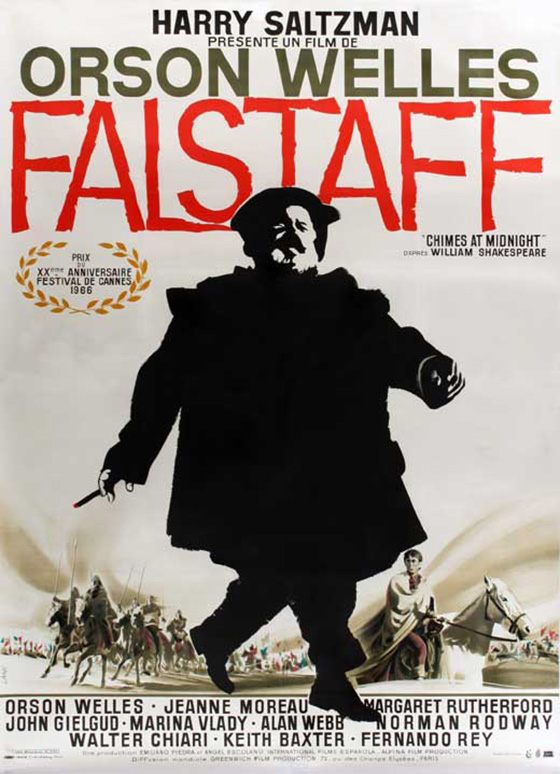

Chimes at Midnight, aka Falstaff (1965), is one of the last films Orson Welles would complete as director. What would follow was the TV film The Immortal Story (1966) and the mischievous documentary F for Fake (1973), along with many reels of footage for uncompleted projects: Don Quixote, The Deep, and The Other Side of the Wind. Chimes at Midnight not only has the feel of a passion project but a last hurrah, a great, indulgent, drunken feast while the wolves are at the door. Even though Welles never stopped working up until his death in 1985, this film feels like a swan song, the work of a great auteur who fears it might be the last film he ever gets to make. Which makes sense: increasingly, his films were taking years to complete, and they were largely independent productions that he made by the skin of his teeth. Chimes at Midnight took two years to shoot, as Welles struggled to find financing. But the film doesn’t look cobbled together. It is of a piece, mournful, joyous, and mad. As Falstaff (Welles) wanders slowly into the frame with his senile companion Shallow (Alan Webb, The Taming of the Shrew), he says with a sad smile, “We have heard the chimes at midnight, Master Robert Shallow.” Shallow replies, over and over, “Jesus, the days that we have seen!” The moment is drawn from Henry IV, Part 2, but Welles uses it as his film’s prologue. This is a film about a life fully lived drawing to a close. Welles saw himself in Falstaff, and felt he was destined to play the character – and so he did, time and again, for the stage: first in a Broadway play, Five Kings (1939), restructuring five Shakespeare plays to make Falstaff the central character, and later in a reworking called Chimes at Midnight (1960). The 1965 film adaptation of his play finds a Welles who had come, over his indulgent life, to physically resemble Falstaff. He was Falstaff, and no better Falstaff has graced the cinema. The chimes at midnight were ringing for Welles’ career as a filmmaker, and just before the opening titles his bearded face fills the screen, and he grins those chimes down.

Fernando Rey as the Earl of Worcester, in the halls of Henry IV.

Chimes at Midnight has long been regarded as one of the director’s finest achievements, but thanks to some rights entanglements it’s been difficult to see except for bootleg copies or YouTube. A new restoration of the film was screened April 11 at the Wisconsin Film Festival in honor of the director’s 100th birthday, and as it circulates through other film festivals, word is that it will be headed to Blu-Ray soon for the U.S. (it’s already been announced for a U.K. release on Blu-Ray this summer). I look forward to the release, mainly because I want to watch the film with subtitles. Chimes at Midnight has a muddy, dubbed soundtrack (the film was shot in Spain with some Spanish actors, including the great Fernando Rey), which is the only evident sign of its seat-of-the-pants production. In Roger Ebert’s four-star review from 1968, he wrote of the sound issues: “Welles saved money but sometimes lost clarity.” Therefore, a familiarity with Shakespeare (in particular Henry IV Parts 1 & 2) will help the viewing experience, because much of the time you’ll have a difficult time making out the dialogue. But if you can get past the often murky audio, the plot is still simple enough to follow, and Welles’ visual talents are undiminished. After slaying Richard II, Henry IV (Sir John Gielgud, Julius Caesar) takes the throne and refuses to liberate the true heir, Mortimer, held captive in Wales. Mortimer’s cousins (Rey, Norman Rodway, and José Nieto) plot a rebellion, while Prince Hal (Keith Baxter) – the future Henry V – spends all his time with John Falstaff and his hard-drinking company of rogues and prostitutes (including Jeanne Moreau). Chimes at Midnight is a tale of two worlds: the royals and the paupers, the latter often parodying the former, such as in a memorable sequence when Falstaff impersonates Henry IV with a mock court and a pot for a crown. But inevitably Prince Hal must be drawn back to his responsibilities, at the tragic expense of his portly mentor.

Falstaff (Orson Welles) impersonates the King for the amusement of Prince Hal (Keith Baxter).

The centerpiece of Chimes is a battle sequence which was one of the most spectacular ever shot, to rival Olivier’s Henry V (1944), but grittier, and more realistic and brutal. Welles first shows us the knights, in their awkward suits of armor, being lowered onto horses by pulleys strung over trees. Falstaff, who in full armor looks like a cannonball with legs, is too heavy to be lifted onto his horse, and is dropped unceremoniously to the ground. (The horse should be grateful.) He spends the rest of the battle scurrying through the bushes while the rest of the men do the real fighting. Welles begins with charging horses and riders being lanced into the air, but by the ignoble end, warriors are splayed in the mud, clubbing each other (or their horses) senseless. After Hal slays his rival Hotspur, Falstaff drags the body to the king and attempts to take credit, so he might profit with a title. Despite behavior like this, it stings when Hal finally assumes the throne and rebukes Falstaff before his court, closing their friendship with abrupt humiliation. This is the key moment of Chimes, its heart and purpose. Like Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencratz and Guildenstern are Dead (1966), Welles is inverting Shakespeare to spotlight the characters in the shadows, a smaller tragedy occurring within the Tragedy. But whereas Stoppard relies on wordplay and wit, Welles emphasizes visual design to make his points. The powerful are depicted as towering giants, the camera low to the ground, rays of heavenly sunlight occasionally framing them. Others he dwarfs with his camera. This occurs in an earlier scene in which Hotspur fumes helplessly before Worcester (Hotspur looks two feet tall), and it is echoed again in the pivotal moment in which Falstaff appears before Henry V, no longer Prince Hal. Before, Falstaff seemed large enough to fill the room, but now Hal towers above him, and turns his back on him. Falstaff the mountain has now just become a bump in the road, and Hal drives right over him. But Chimes celebrates what he was, warts and all, and if it is Falstaff’s epilogue, it might act as a fitting one for Welles, too: extravagant, delirious, flawed, spectacular.