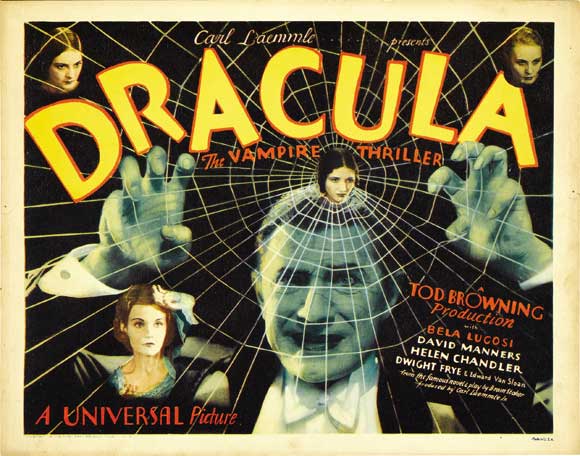

This week Turner Classic Movies presented an in-theater event, a double feature of Dracula (1931) and the Spanish language alternate version (with a Spanish-speaking cast, filmed using the same sets). The screening I attended was almost empty, which was a shame, though there were benefits: those who did show up were quiet and respectful, allowing the eerie silences of the films to dominate. It’s not surprising that so few attended, or that one couple left after the Tod Browning film; it’s really an academic exercise to watch both films back to back. A more audience-pleasing double feature might have paired it with a different Universal monster film, a different Bela Lugosi picture, or even the Hammer Dracula, which adapts the novel in a completely different way. But the Spanish Dracula, directed by George Melford, follows the same script as Browning’s film, and in turn is derived from the same stage play. It’s the same Dracula, but pressed through the looking-glass.

The Browning/Lugosi version is one of the most influential horror films ever made, and Lugosi’s interpretation of the Count is beyond iconic – it’s a potent cultural force, like the creation of Sherlock Holmes, the arrival of Shakespeare’s canon, or the “Visit from St. Nicholas” Santa Claus. (You can say the same for Karloff’s Frankenstein monster, Lon Chaney Jr.’s Wolf Man, and Jack Pierce’s makeup designs.) Nevertheless, it’s become popular in recent decades to dismiss the 1931 film as too stagey, too dull, too un-cinematic, with favor given instead to James Whale’s pair of Frankenstein films and, yes, the Spanish-language Dracula. TCM’s Ben Mankiewicz, introducing the double feature, used the Dracula rivalry as the principal reason to remain seated for both films – watch them together and decide for yourself which is better. This is the first premium-priced theater event in which the audience is encouraged to take notes and treat cinema like a sporting event. From shot to shot, it’s hard not to mark the similarities and variances. Is this angle better in Browning’s film or Melford’s? Or is it just different? Isn’t this shot the same in both? Is that Lugosi wandering into Melford’s film? (It is.) During a double feature in which both films feature no musical soundtracks (apart from the opening credits) and share the same script, it’s nearly the only factor that can hold your attention. Which means that my wife and I couldn’t maintain the respectful silence during the Spanish version. We had to play Mankiewicz’s game. A lot of whispering back and forth.

Dracula (Bela Lugosi) and Mina (Helen Chandler).

The lack of a composer (or even library music) for both films has become one of their most defining characteristics. This wasn’t uncommon for early talkies, still working through the complexities and expense of a soundtrack. The downside is that certain moments which are intended to be dramatic, such as Lugosi recoiling from Edward Van Sloan’s mirror and crucifix, Dracula’s staking and the final triumph of Van Helsing, Mina, and Jonathan Harker, play too flat. But the film gains an otherworldly, hypnotic quality as a result, enhanced by seeing it on the big screen. It might be a happy accident, but since this is a film in which hypnosis plays such a central role, it works to the film’s benefit that moments of the eerie play to almost perfect silence. Watching this in a theater, more than ever I could understand why Dracula made such an impact in 1931. It is a completely macabre film, full of flapping and scuttling creatures of the night, of crypts and cobwebs and close-ups of Lugosi’s glaring eyes. It’s a mistake to render almost the entire film music-free, but the damage isn’t severe. Without a composer’s accompaniment, the result is a film that drifts somewhere between dream and documentary.

Lugosi’s Dracula makes his first appearance.

Lugosi was the Hungarian star of the hit stage production of Dracula, but Universal approached him for the part almost reluctantly; their preferred choice, Lon Chaney, passed away just prior to production. Obviously, it is now difficult to imagine anyone else in the role, though the existence of the Spanish version helps us do just that. Lugosi’s thick Hungarian accent – in a soundstage-bound Hollywood world where accents were often phony or lacking – stands out for its authenticity, but also its otherness. Contextually, the Count is a stranger in London. (Never mind that so much of London is the Universal Studios version of it, and a stranger to itself. This disconnect is even broader in the alternate film, where London becomes Spanish!) We can feel how out of place Dracula is, emphasized by his lack of a reflection and tendency to become a bat. No wonder that contemporary adaptations tend to make Dracula a more sympathetic character; it’s easy to sympathize with an outsider who can’t fit in. (Similarly, some recent retellings have played with the inherent xenophobia of the original story, such as Guy Maddin’s Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary.) Lugosi clutches his cape about his body like the last vestige of home; it’s his security blanket, like those three coffins of Transylvanian soil. The visual similarity of the cape to bat-wings is surely intentional – when he’s in human shape, the cape is his wings – and now we’ve grown accustomed to this visual association, thanks to the countless vampire films that followed. At the time, this was ingenuity. Browning, Lugosi, and producer Carl Laemmle Jr. had to invent this stuff before it could be imitated, toyed with, or parodied.

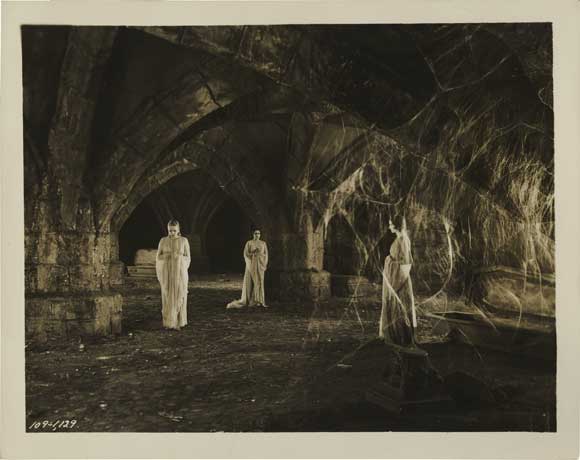

Publicity still of Dracula’s wives in their crypt.

Browning had previously directed a number of silent films including the Lon Chaney vehicles The Unholy Three (1925), The Unknown (1927), London After Midnight (1927), and West of Zanzibar (1928). Like Chaney, he was already closely associated with the macabre, and after Dracula would make the indelible Freaks (1932). Dracula could benefit from more of Browning’s freaky imagination, as he seems to be a bit constricted by the stage play. The most arresting scenes are those in Dracula’s castle – though the same could be said of Bram Stoker’s book. In particular, the introduction of Lugosi is spectacular. First just a crooked hand angles its way out of a coffin deep in the castle crypt; intercut are shots of castle wildlife, including possums. Then Lugosi is standing there, the light fixed on his mesmerizing eyes. He seems perturbed. He’s flanked by his wives, dragging their gowns soundlessly. These are not human beings – the audience immediately understands. They are part of the crypt, one with the nocturnal creatures; this is their natural environment. So we get the joke later on, when Mina (Helen Chandler) says she can’t wait to see some life in Carfax Abbey again. Carfax Abbey appeals to Dracula because it’s decrepit, and he has no life to provide.

Dwight Frye as Renfield

Lugosi isn’t the only irreplaceable element of Browning’s film. The cast also boasts Edward Van Sloan (The Mummy) as an excellent, professorial and cunning Van Helsing, and Dwight Frye (Frankenstein’s Fritz) as Renfield. Smartly, the screenplay replaces Jonathan Harker with Renfield in the opening scenes, so we get to witness the man who’s presumably our dashing hero crumble into sniveling submission, lunacy, and nascent vampirism. Frye reveals the transformation in a single shot, as he appears down the steps in the ship’s hold laughing with a low, unnerving contentedness. Mankind is doomed, says that laugh: the Master has come. As a result of this plot adjustment, Harker (David Manners) remains in ignorance of Dracula’s threat for most of the film, which means he’s a bit of a dope, unfortunately, all too eager to acquiesce to sweet Mina’s requests to remove the wolfsbane and cross from her immediate vicinity. But Frye remains interesting throughout the film, even as he continually breaks free of his cell with a consistency that should alarm the sanitarium staff more than it does.

The Spanish version of Dracula features a different cast, including Pablo Álvarez Rubio as Renfield and Carlos Villarías as Dracula.

Therefore it’s easy to acknowledge the immediate deficiencies of the Spanish version: no Lugosi, no Frye, no Van Sloan. No Browning either, though here there is room to improve, and director George Melford does find some opportunities. As Ben Mankiewicz points out, Browning shot during the daylight hours and Melford at night, his crew viewing Browning’s rushes for inspiration – and ways to do better. One major improvement is the climax of the film, which is more exciting and logical in the Spanish version. We see the sun rising, which explains why Dracula takes refuge in his coffin. The final shot of the Spanish version, with “Juan” Harker (Barry Norton) accompanying “Eva” (Lupita Tovar, as this version’s Mina character) toward the daylight while Van Helsing, below the stairs, prepares to dispose of Renfield’s body, is edited as a visual crescendo (and even contains a bit of library music) which I prefer to the abrupt, subdued Browning take. The scenes involving Eva’s seduction toward the dark side are infused with greater eroticism (in part thanks to a semi-transparent nightgown) and a greater excitement for her reawakening. This isn’t just to Melford’s credit, but to a rich performance by Lupita Tovar. There are other moments when Melford makes better use of the giant Universal sets: we can see them better, make out details that were hidden before, particularly in Dracula’s castle. Best of all, we learn what became of Lucy. In Browning’s version, we briefly see the vampire Lucy (Frances Dade) on the hunt for children to bite, but then she’s oddly forgotten. The Spanish language version, which seems to include more of the original script (and is longer by almost half an hour), features a brief moment in which Harker and Van Helsing emerge from a graveyard stating that they’ve just dispatched Lucy for good. Perhaps because it hasn’t been edited as tightly, the Spanish version benefits from smoother storytelling.

Lupita Tovar as Eva, the Spanish-language version’s Mina.

But often the film is just different. When you view the two movies side by side, those differences are compelling, but one take is not necessarily better than the other. In the Spanish film, my wife and I were both amused by a clumsy possum that plummets through a spider web in Dracula’s crypt. A bit of comic relief between the sanitarium guard and a nurse has a different gag in both films – the joke in the Spanish version is more straightforward; Browning’s might be slightly more clever. When Dracula (Carlos Villarías) appears before Harker on the great flight of stairs in the castle, Melford’s camera climbs the stairs – a bit shakily, in these pre-Steadicam days, but certainly an attempt to provide some more energy to the moment. And while Browning pointedly avoids showing Dracula climbing out of his coffin, preferring the abrupt cut to him standing in the room, Melford illustrates the moment with a cloud of smoke billowing from the coffin lid as Dracula rises, a more overtly supernatural touch. Which is better? I like Browning’s take, but – well – it’s small stuff. And both directors prove the rule that bats on strings look nothing like real bats. Alas, Carol Villarías, in his evil leer, is simply too goofy to be the better Count; although he bears a passing resemblance to Lugosi, it’s only by way of Gomez Addams. There is nothing wrong with Pablo Álvarez Rubio’s interpretation of Renfield, which is considerably louder than Dwight Frye’s. But isn’t it more unsettling when the lunatic is laughing softly, as though possessed of knowledge that you don’t have? I know where Rubio’s Renfield stands, but Frye always seems like he’s up to something.

The Dracula double feature live theater event, sponsored by Turner Classic Movies.

So, if a scorecard must be kept, the winner must be the Browning picture. Yes, the Spanish film is a fascinating product – we should be eternally thankful that it hasn’t been lost to time – and it’s a good horror film too. Highlights include more coherent storytelling and the treatment of Mina/Eva, who becomes a more interesting and sensual character. But any Dracula film will live and die on its Dracula, and Browning had Lugosi. Lugosi enjoyed a brief run of memorable roles before quickly being relegated to the sidelines, as though it were more important to have his name on the marquee than to give him a prominent role. A good example of this is 1942’s Night Monster, an Old Dark House tale of an exotic foreigner who uses mesmerism to manipulate high society. Who does Lugosi play? The butler. If Hollywood ultimately mistreated Lugosi, Dracula is a worthy high watermark in his career, a film which, for all its endlessly argued flaws, can still trap you in its cobwebs with ease.