Aleksandr Ptushko’s Russian fairy tale spectacular Sadko (1952), recipient of the Silver Lion for Best Director at the Venice International Film Festival, has a purity of purpose, a grand vision, and a childlike innocence – this is the sort of film where someone might burst into song, without the film ever qualifying as a musical. It is, in fact, very much like a Walt Disney animated fairy tale, which is one of the reasons why Ptushko was considered the Russian Walt Disney. It reached America in a somewhat abbreviated and badly dubbed form as The Magic Voyage of Sinbad in 1962, ten years after its production, and this is its best known incarnation in the U.S. to this day, thanks to its inclusion in the classic years of Mystery Science Theater 3000. As MST3K points out repeatedly, the hero of the film can’t possibly be Sinbad (anyone with a rudimentary knowledge of international cultures ought to be able to figure that out by the set design and costumes; and “Sinbad” would be quite overdressed for Baghdad). The title was chosen as a cash-in on The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), and there was a greater chance of box office success if claiming to be an Arabian Nights fantasy, as opposed to an import from the USSR (the film was distributed in the U.S. the same year as the Cuban Missile Crisis). But if audiences were duped, at least they were duped into watching a good film – albeit one buried under confusing references to the Arabian Nights. Ptushko’s film was a major accomplishment in Russian cinema, and it toured the world for years before reaching the States. Many of the scenes involve teeming extras, crowded so thickly that you can’t see the ground; and, typical for animator Ptushko’s live action fantasies, hardly a moment goes by without some kind of special effect. Sure, there’s no Harryhausen-style stop motion animation, but Ptushko, as usual, blends many different effects, from one shot to the next or overlapping in the same scene: an effective way to fool the eye. Even when you catch the trickery – for example, a model miniature of our hero, replete with fluttering cape, playing his instrument on a storm-tossed miniature raft – it’s hard not to admire the amount of detail and effort that went into it.

Sadko (Sergei Stolyarov) finds the gold-finned fish with the aid of a princess of the sea.

The hero’s name is actually Sadko, and he derives from Russian oral narrative, a “bylina,” or epic poem. The setting is not Baghdad, but Novgorod, a metropolis on Lake Ilmen and the Volkhov River in the northwestern and Scandinavian-influenced corner of Kievan Rus’, the Russia before the Tsars. Novgorod was a city of minstrels and merchants, and Sadko was both. In the story, he is an Orpheus figure, playing his maple gusli (a Russian harp) to magical effect. He travels to an undersea kingdom where he’s offered the hand of one of the three hundred daughters of the King of the Sea, but rejects them all for the love of a servant girl. Nonetheless, he rises from poverty to become the wealthiest merchant in Novgorod thanks to the wealth acquired from the sea kingdom, and he builds a great cathedral in the city. The bylina ends, “Sadko no longer traveled to the blue sea; Sadko started living his life in Novgorod.” Rimsky-Korsakov adapted the bylina into an opera called Sadko in 1898, and it is this work upon which Ptushko’s Sadko is principally based. To fill out the film’s 85 minutes, he expands the plot to include a quest for the Bird of Happiness. Sergei Stolyarov plays Sadko, looking very much the Errol Flynn and introduced singing “Farewell, farewell, O Volga River,” as he travels to Novgorod. In the city he finds a man so poor that he sells himself into slavery. The streets are filled with misery, but in a great hall, the wealthiest merchants boast of their riches. Sadko suggests that the merchants gather ships and travel the world to bring glory to the city, but his suggestion is flatly rejected. In anger he declares that he will strip them of their wealth: “I’ll carpet the streets with your silks! I’ll dress the poor in your brocades!” At night he plays his gusli, wondering how he’s going to gather ships; the enchantment of his playing catches the attention of Vasya (Ninel Myshkova), daughter of the King of the Sea. Falling in love with him, she says that if he fishes the next day, she will guide his net to the rare gold-finned fish. With this promise made, Sadko announces to the downtrodden citizens that he will catch gold-finned fish to bring glory to Novgorod. After this miraculous accomplishment is achieved, Princess Vasya transforms the last of his fish into a stack of gold coins, which he uses to purchase a fleet of ships. He embarks with a crew, including the wily Trifon (Mikhail Troyanovsky), the apprentice minstrel Ivashka (B. Surovtsev), and Hercules-like strongman Vyshata (Nadir Malishevsky), to find the Bird of Happiness and return it to the city. (This legend bears a strong similarity to the Greek myth of Jason and the Argonauts.) Meanwhile, his one true love, the humble Lyubava (Alla Larionova), looks out toward the sea month after month, awaiting their reunion.

The Maharaja, riding an elephant, and his great entourage in India.

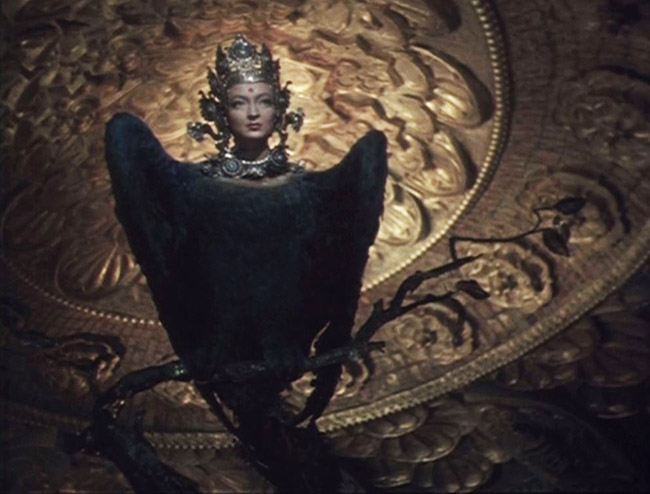

If you watch Sadko in the innocent frame of mind that is necessary for Russian fairy tale films – which were a major genre in Soviet cinema – you’ll find a satisfying, sometimes delightful fable told with a surprising amount of splendor. If there’s a key flaw, it’s that the film is mostly set-up, with the adventure itself being a little too brief. Sadko and his crew make only two stops on their voyage for the Bird of Happiness. First they visit a land of Norsemen, and engage in a battle on the steep crags overlooking the sea. Ptushko shows us black cliffs with Vikings clinging to the sides of rocks like spiky-headed sea anemone. At one point, Sadko becomes cornered at the edge of a cliff, and boy minstrel Ivashka tosses him his sword from across the expanse; then Sadko begins cutting his way back down through the Norsemen. The scene looks like an N.C. Wyeth illustration. But the film’s centerpiece moment of spectacle comes when Sadko anchors in an Indian port. The Indian city has vast, ancient architecture, and hundreds of extras crowd the streets. A procession emerges from the palace gates, the Maharaja riding in a palanquin atop an elephant. Sadko learns that the Maharaja keeps a phoenix, which might be the Bird of Happiness, so he offers the prince a trade: his magic horse for the phoenix. Unwilling to give up his prized possession so easily, the Maharaja challenges him instead to a game of chess. When Sadko wins, he is allowed access to a secret chamber in the palace, high up a winding stair. The phoenix sits on her perch; she has the head of a woman. She sings the men to sleep, which Ptushko depicts using rear projection to toss and turn the background. Only Sadko’s magic gusli can stop her spell, and he carries her out of the city; when he’s threatened by the prince’s army, he has the phoenix sing them to sleep, and the hundreds of extras – and an elephant! – collapse at once. I would argue that this entire passage ranks among the most beautifully realized fantasy setpieces of the 1950’s. The phoenix itself is a stunner, convincingly realized, gorgeously photographed.

The Phoenix (Lidiya Vertinskaya).

Realizing that the somewhat sinister phoenix (when he tries to touch it, it hisses at him) can’t possibly be the Bird of Happiness, Sadko travels on – but by the time they reach Egypt, he and his crewmates are too weary to continue. They turn back toward Novgorod, but on the way, the King of the Sea, angry that they haven’t paid proper tribute, strikes at them with a tempest. Sadko travels beneath the waters to visit the King and Queen directly. Here, Ptushko’s special effects show their limitations; the royal court looks like it’s been decorated for an undersea-themed high school prom, and the octopus hanging overhead like a twitching chandelier, its glowing eyes blinking in and out, makes one wonder if this is what the “borrowed” octopus in Bride of the Monster would have looked like if Ed Wood had remembered to steal its motor. If the tableau is reminiscent of the “Under the Sea” number in The Little Mermaid, it only serves as a reminder of why some ideas are best left to animation. Sadko is assisted in his escape by Princess Vasya, who gives him a seahorse that he rides out of the Sea King’s domain. Here it’s easy to see why the Americanized, “Sinbad” dub of the film became an MST3K favorite. In The Mystery Science Theater 3000 Amazing Colossal Episode Guide, Kevin Murphy (Tom Servo) describes the film as being “in some places unbelievably well shot and beautiful, as with the scenes in India; in others, such as the underwater musical number with Neptune, you could shoot whole popcorn kernels out your nose laughing.” This can be a very silly movie. But watch the film without the silhouettes on the bottom of the screen and take off your irony hat, and the film’s storybook qualities shine through. By the time Sadko returns to Novgorod without his Bird of Happiness and declares, “There is nothing fairer than our native home. Here is happiness!”, you might discover the appeal of Ptushko’s pure-hearted imagination.