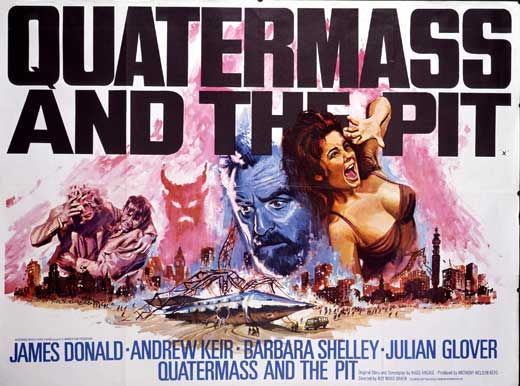

One of the most admirable qualities of the science fiction scripts of the late Nigel Kneale is that their stories proceed through the scientific method, albeit leading to fantastic conclusions. They are examples of true science fiction – a rare commodity in TV and film. Most of his screenwriting was done for television, but among his feature work, none stands taller than Quatermass and the Pit (aka Five Million Years to Earth, 1967) for Hammer Films. It was the third and final Hammer Quatermass following The Quatermass Xperiment (aka The Creeping Unknown, 1955) and Quatermass 2 (aka Enemy from Space, 1957), and the truest to Kneale’s vision. The first films brought in an American star, Brian Donlevy, to portray Professor Quatermass, whose origins (in Kneale’s original serials for television) are as British as Doctor Who’s, and Kneale was furious at Donlevy’s bullheaded approach to the character. Nonetheless both films, in condensing the sprawling miniseries from which they were based, kept intact a very Kneale-like scientific curiosity and wide-eyed fascination for all permutations of alien grotesquerie. This quality is also on display in a Kneale-scripted Hammer film that isn’t part of the Quatermass series, the underrated chiller The Abominable Snowman (1957). Quatermass and the Pit, arriving a decade after these films and directed by Roy Ward Baker (A Night to Remember), attempts to right previous wrongs by replacing Donlevy with Andrew Keir, a man who radiates formidable intelligence, and who had appeared in Hammer’s The Pirates of Blood River (1962), The Devil-Ship Pirates (1964), and, most notably, Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966), as the vampire-slaying Father Sandor. Kneale’s script takes the original 1958-59 serial Quatermass and the Pit and condenses it down to the major plot elements and twists, giving it an intense, anxious tone, even if it still doesn’t contain the sort of action that one usually expects from a science fiction thriller. That’s because it plays as a mystery – one that doesn’t even reveal, for quite a while, what genre it is. It respects the viewer’s intelligence; it expects us to pay attention, and rewards handsomely.

Professor Quatermass (Andrew Keir) explores a “haunted house” in Hobbs End.

Quatermass, who designed the rocket that sent a man into space (disastrously) in The Quatermass Xperiment, is introduced in this film arguing with a Colonel Breen (Julian Glover of The Empire Strikes Back and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade) over the militarization of his space exploration program. The British government intends to build bases on the Moon to “police” the Earth with ballistic missiles. The two men are sidelined by a discovery at an excavation in a London Underground station, Hobbs End: what appears to be a giant unexploded bomb buried in the earth. The archaeological dig is being led by Dr. Matthew Roney (James Donald, The Bridge on the River Kwai, The Great Escape), with his assistant Barbara Judd (Barbara Shelley, Dracula: Prince of Darkness, The Gorgon). The two have discovered a humanoid skull at Hobbs End which they believe dates back, astonishingly, five million years. After Quatermass and the Colonel arrive, Roney realizes that the skull was actually inside the “bomb.” Furthermore, a curious detail excites Quatermass’ interest when he learns that the homes in this section of Hobbs End were abandoned before the war due to local superstitions and remain derelict. A police inspector who lived in Hobbs End at the time, and guides the professor and Barbara through one of the empty houses, describes “noises, bumps, even things being seen.” Barbara finds claw-like scratches on the walls. As they look further into the paranormal activity reported in the area, including reports of horned imps, Quatermass also notes that it was once called “Hob’s End,” and “Hob” is a name for the Devil.

The discovery of an alien cockpit, where Quatermass finds its dead inhabitants.

Having crept into the realm of supernatural horror, the story then swerves into high-concept science fiction. Drilling into the “bomb” creates a violent psychic and physical disturbance. Inside what appears to be an alien ship, the bodies of an insect-like race are discovered. They resemble the imps of Hob’s Lane legend, but deteriorate quickly when exposed to the air. Barbara demonstrates a psychic connection with the creatures and their craft, and we learn that the extraterrestrials originated from Mars. Most disturbingly, because the Martians could not survive in Earth’s atmosphere, they seem to have genetically altered apes five million years ago in order to create a Martian-influenced race that could live on in their stead. These evolved into a parallel human race still psychically connected to the Martians to establish a Martian colony on Earth; Barbara is one of them, and soon we learn that so is Quatermass. A malevolent psychic energy is transmitted throughout London, spurring telekinesis-fueled violence and riots as those descended from the Martians try to exterminate everyone else, a reflection of the violent, race-purging mentality of Mars. But before this spectacular finale, Quatermass and the Pit acts as an ever-shifting puzzle, with multiple possibilities explored before the truth begins to reveal itself; at one point, someone even suggests the bomb was WWII Nazi propaganda to persuade England of an alien invasion.

Barbara (Barbara Shelley) unlocks her ancient racial origins and latent telekinetic abilities.

To bring this story to the big screen, the star of the serial, André Morell, was curiously replaced by Keir; odd, because Morell was himself a part of Hammer’s standard repertory players. Perhaps it was simply to separate the serial from the film – but Keir is excellent in the part, demonstrating a stubbornness, intelligence, and empathy which is more well-rounded than Donlevy’s performance in the 50’s films. Supporting players Donald, Shelley, and Glover are equally outstanding, and reveal different facets to their personalities as the story progresses. This is an actor’s film, with a paucity of special effects until the big finale, and one of the film’s most effective moments is its unusual ending credits, as we watch Keir and Shelley recover from their manipulation and absorb the impact of what they’ve just learned and what’s just unfolded. Unfortunately, the one glaring flaw in the film is when the special effects really need to deliver: an admittedly far-fetched scene where Shelley’s character mentally channels her racial origins into a television monitor, allowing a glimpse of the race wars of Mars. Here the insectoid Martians are depicted as phony-looking miniatures. A scene meant to inspire awe (the soundtrack is ominously silent while the actors are transfixed by the images on the screen) plays ludicrously. But this is a small bit of a very special film, a Hammer movie like nothing else they produced. Without quite being a Hammer horror, Kneale’s story is somehow more disturbing than most of the studio’s conventional horror films. While The Devil Rides Out (1968) and every movie where crucifixes conquer the vampires inhabit a Christian universe of good vs. evil, Kneale offers the less reassuring suggestion that we have evil encoded by malevolent designers at the cellular level, ready to be triggered at any moment, at which point we will lose our personality and moral compass. When Quatermass himself succumbs to that influence, all hope seems to be lost. The solution, neatly, utilizes both scientific and supernatural principles. In this, Kneale’s script reminds me of Richard Matheson’s 1971 novel Hell House, which also explores both supernatural and (pseudo-)scientific explanations for its haunted house scenario before splitting the difference in the finale. Kneale’s story is not entirely original – it has at least one antecedent in Arthur C. Clarke’s 1953 novel Childhood’s End – but very little of its kind had been seen on screens big or small. Its influence was great. John Carpenter has cited Quatermass and the Pit as an inspiration (you can see glimpses in Prince of Darkness and Ghosts of Mars), and similar science fiction stories include Lifeforce (1985) and the “Inhuman” storyline in Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. In writing his original serial, Kneale was inspired by the race riots of Nottingham and Notting Hill against black West Indies migrants. Almost a decade later, the tale found new relevance in the riots of the late 1960’s. Sadly, it’s just as relevant today, with the Western paranoia and resentment toward immigrants and Muslims and the resurgence of white supremacist groups. Maybe some of us have Martian blood boiling deep inside, and seek to purge those who are different. Any one of us could be capable of committing sudden violence. This is why Quatermass and the Pit remains so very unsettling 50 years later.