RKO’s Pre-Code Secrets of the French Police (1932) proves that sensationalist, exploitative pulp was passing itself off as authentic crime procedural decades before the modern TV incarnations. The film, produced by David O. Selznick and directed by A. Edward Sutherland (Murders in the Zoo), is based on a popular series of articles by crime writer H. Ashton Wolfe which appeared in the Hearst papers Sunday supplement The American Weekly. The magazine, which ran for half a century, in its 20’s and 30’s heyday featured spectacular contributions from many notable artists including Alberto Vargas, Edmund Dulac, Lee Conrey and others, illustrating lurid tales of suspense, crime, and detective work. The film begins with a copy of the magazine opened to an installment of Wolfe’s Secrets of the Sûreté, The French Detective Police, insistent (as Selznick often was) on the faithfulness to its source material. But it was a little more complicated than that. Wolfe, author of books like The Forgotten Clue: Stories of the Parisian Sûreté With an Account of Its Methods, was a fascinating and problematic character. His standard lead detective, a forensically minded Sherlock Holmes, was Philip Woodley-Foxe, a thinly-veiled stand-in for Wolfe himself, and he insisted on the veracity of many details of his stories. Mark Gabrish Conlan writes at Movie Magg that Wolfe “claimed to have been a police detective in Lyons, France and to have written the articles based on his real experiences with the force — only while they were checking out the legalities of using real people’s names in the film…RKO’s legal department discovered that Ashton Wolfe was in fact a con artist wanted on swindling charges in both Britain and France (which itself suggests the plot for a very interesting thriller). So Frank Morgan ended up playing the fictitious ‘St. Cyr’ instead of Ashton Wolfe — or at least the glamorous law-enforcer identity Ashton Wolfe had created for himself.”

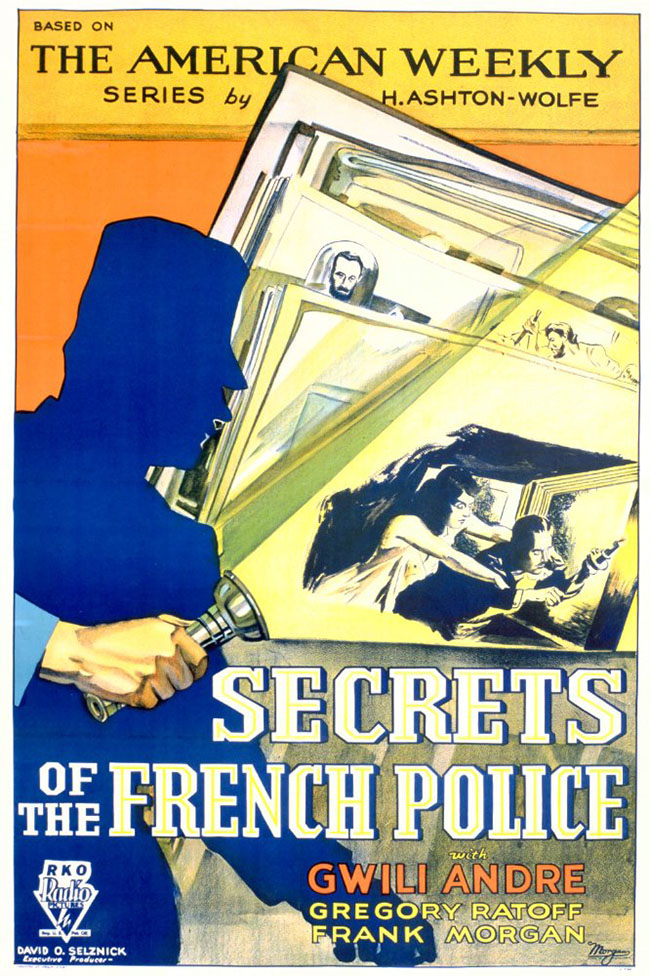

The film’s opening underlines that it’s an adaptation of the American Weekly series by H. Ashton Wolfe.

The film wastes no time in getting confusing. After we witness a grim funeral for murdered French police officer Brigadier Danton, the plot dashes off in several directions at once without properly introducing anybody. As you’d expect from an early 30’s Hollywood film set in Paris, accents are a grab-bag of French, something meant to pass as French, and unapologetically American. François St. Cyr (Frank Morgan of The Wizard of Oz fame) vows to avenge Danton’s death, and begins following the clues, beginning with the cigarette ash left near his body. A pickpocket named Leon Renault (John Warburton, Saratoga Trunk) romances a flower girl, Eugenie Dorain (Gwili Andre, Roar of the Dragon). A Russian in a rather Gothic chateau, Han Moloff (Gregory Ratoff, All About Eve), places a telegram declaring that he has discovered the lost Princess Anastasia of the Romanovs. To which you might justifiably say, “Wait, slow down – what?” Well, it will all come together, but not in ways that you might expect, or even in the genre in which the story started.

Eugenie (Gwili Andre) and Moloff (Gregory Ratoff).

Ratoff gives what seems to be a Bela Lugosi-inspired performance, speaking with slow, commanding menace. He is a hypnotist with shades of Svengali, kidnapping Eugenie, murdering her elderly guardian, and placing her under his spell so that she will claim to be Anastasia, daughter of Tsar Nicholas II who was rumored to have escaped assassination in 1918. He intends to bring her before the Grand Duke Maxim (Arnold Korff, Diary of a Lost Girl), who knew the real Anastasia as a little girl, and convince him of her authenticity, collecting the reward money. The problem is that every time she sees potted flowers in Moloff’s estate, she switches automatically into flower girl mode, dreamily lifting them up and offering them for sale. This, by the way, is a good indication of the depth of character development in this thoroughly pulp film. Eugenie is the Flower Girl, nothing more. Her smooth-talking, thieving boyfriend Renault (in the mold of Leslie Charteris’ Simon Templar, aka The Saint), who proudly claims that he’s a nationalist and will never rob a Frenchman, is recruited by St. Cyr to break into Moloff’s heavily guarded chateau. Deeper inside those walls we get the first signs of Moloff’s truly malevolent persona: he has constructed a mad scientist’s laboratory and loves to embalm women with formaldehyde and encase their bodies in statues which he poses about his home. Naturally. When Eugenie spoils his scheme by asking the Grand Duke if he’d like to buy some of her flowers (“No more cut flowers in the house!” Moloff fumes to his staff), Moloff sets about embalming her. Only St. Cyr and Renault can save her in time.

Moloff works his embalming technique.

Some nods are made to the forensic methods which Wolfe detailed in his stories. In one fascinating scene, detectives use descriptions of a suspect to build a sketch out of puzzle-like pieces hung on a giant wall. You may ask why the portrait needed to be wall-sized, but it makes for a spectacular image. Other gadgets and strange inventions are employed, such as Moloff’s installation of a movie projector and sound effects machine inside a building at the end of a bridge. As the Grand Duke’s car crosses the bridge, the projected image of another (colossal) vehicle appears to be charging right at him; his driver spins the wheel and the car crashes below, killing its passengers. Yet it’s the final act which is most memorable, surprisingly aligning Secrets of the French Police with other early-30’s crime/horror films like the superior and essential Michael Curtiz films Doctor X (1932) and The Mystery of the Wax Museum (1933). Tellingly, the film also reuses sets from the atmospheric chiller The Most Dangerous Game (1932). In a climactic scene which earns its horror movie bona fides, a desperate, handcuffed Moloff reaches out toward the electrodes of his Frankenstein-inspired mad scientist machine. His hands begin to smoke, and the handcuffs spark and separate, freeing him – but he dies in the process. Perhaps this and the creepy embalming scene might have been handled less explicitly after the Production Code, but the true Pre-Code element is very brief nudity from one of Moloff’s victims. Above all Secrets of the French Police is a confused mishmash of a film, entertainment at the cost of coherency, good taste, or common sense. True crime? Of course not. Which makes it perfect late night viewing with a 30’s-inspired cocktail of your choice. The film is included on last year’s Forbidden Hollywood Volume 10.