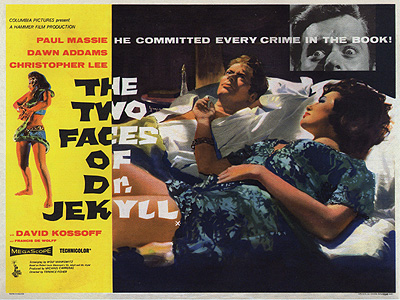

One of the chief defining characteristics of Hammer’s initial run of Gothic horrors in the late 50’s and early 60’s is the resistance to produce traditional, straightforward, or even faithful updates to horror’s canon of literary and cinematic monsters. The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) isn’t particularly beholden to either Mary Shelley’s original or James Whale’s 1931 adaptation, presenting a womanizing, murderous Dr. Frankenstein. Dracula (1958), amidst its extreme compression of the novel’s events and characters, serves up a Jonathan Harker who knows Dracula’s true nature from the start, as well as, of course, a vampire just as seductive as he is monstrous. If The Mummy (1959) were more comparable in plotting to Universal’s earlier cycle, it still distinguished itself with Hammer’s dashes of gore and overt sensuality displayed in eye-popping color. By the time audiences received The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll (aka Jekyll’s Inferno, 1960), perhaps it wasn’t a surprise that Robert Louis Stevenson was not the central attraction. With a literate screenplay by playwright/novelist Wolf Mankowitz and direction by a returning Terence Fisher, the focus turns to sleazy thrills while the central gimmick – the Jekyll/Hyde transformation – is boldly turned upside-down. After taking his special formula, Dr. Jekyll (Canadian actor Paul Massie) doesn’t get buried under makeup like Fredric March, but liberated from it: his beard and middle-aged makeup vanish and he becomes young and handsome.

Hyde (Paul Massie) and Maria (Norma Marla).

It’s not a bad idea on the page, as it places a greater emphasis on how devilish Hyde behaves, rather than how he looks; he becomes a convincing stand-in for handsome, manipulative men on the prowl for women to abuse. But on film, the results are mixed. The beard vanishing shouldn’t be as silly as it is. Of course the story is a fantasy; but for the sole supernatural element to be the erasure or instant regrowth of facial hair is bound to draw a smirk. Massie does look and act quite differently when he transforms from Jekyll into Hyde, and we can suspend disbelief that he isn’t recognized as his alter ego – this much works. But Massie is also the film’s weak link, giving a Hyde performance that can’t exist in March’s shadow because it doesn’t even approach it in terms of intensity. This Hyde is soft-spoken, even a bit fey, interacting with others as though he’s an alien that’s just left his spaceship. It’s a mystery why showgirls would throw themselves at him, unless they think he’s an easy mark. You might argue that Hyde truly is an alien, or at least a newborn, but this approach is at odds with his sadistic nature when it comes to the fore. Massie gives a fantastic leer out of left-field, a Cheshire grin that splits his face in half, and his eyes look truly Wonderland-mad. Then he’s the aloof alien again, as though he wouldn’t know how to strangle a showgirl if he were handed a manual on the subject.

Dr. Jekyll in his laboratory.

Mankowitz’s screenplay spends most of its time in a night club where Hyde meets up with Jekyll’s disloyal friend, a cad named Paul Allen, played marvelously by a cast-against-type Christopher Lee. Paul is an unrepentant gambler with massive debts, leaning constantly on Jekyll’s fortune to bail him out – even while sleeping with Jekyll’s wife Kitty, played just as marvelously by Dawn Addams, who projects a cynicism that’s more effectively shocking than any of the overt horror elements the film offers. Cleverly, Mankowitz establishes right away that Kitty is just as two-faced as her chemically-augmented husband, though she seemingly bears no guilt at stepping out every night with his best friend. Hyde takes a lover in the snake dancer Maria (Norma Marla), but soon targets Paul and Kitty for a scheme of revenge. Mankowitz and Fisher send up Victorian hypocrisy in the traditional manner of past adaptations, but in a taboo-pushing style that’s alternately sophisticated (the blunt depiction of sexual relations) and humorously overwrought (Maria’s dance with her snake climaxes with her plunging the snake’s entire head into her mouth, symbolism that you could almost literally choke on). The night club scenes have an echo in the much later, much superior Hammer film Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), which contains more satirical bite. But The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll is so unusual a horror film that it becomes more fascinating on repeated viewings. There’s something to be said for its commitment to the lurid (as much as 1960 British censors would permit, anyway: a can-can dancing scene is one of the more old-fashioned styles of naughty included here). We spend a disproportionate amount of time in Hyde’s world such that Jekyll becomes an afterthought, which perhaps is for the best. As to killings and violence – there’s not much. But Lee and Addams know their irredeemable characters backward and forward. They are sophisticates for sleaze. They are, improbably, far more interesting in their underhanded ways than the film’s own Hyde. (Even Oliver Reed, who pops up in a too-brief role, steals the screen from Massie.) This is not a particularly deep film, but is attuned to the faces we wear in public and in private. Fisher gifts the shock scenes with expressive framing and color, almost enough for you to forgive an improbable killing by a slow-moving snake. It’s far from Hammer’s best, but it’s a reminder that the studio seldom gave you a tired version of the old chestnuts; they were always striving to do something different and inventive, even in sequels and remakes. In fact, this was not their first Jekyll and Hyde and would not be their last. 1959’s The Ugly Duckling, with Bernard Bresslaw, gave a slapstick treatment to the story, beating The Nutty Professor by four years; and Hammer’s smartest twist on the formula came in 1971’s gender-bending slasher Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde, written by Brian Clemens with liberal doses of black comedy.

Oliver Reed, pre-stardom, makes an early Hammer appearance.

The British label Indicator has released The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll on region-free Blu-ray in the box set Hammer Volume Four: Faces of Fear, alongside The Revenge of Frankenstein (previously reviewed here), Taste of Fear, and The Damned. I expect to be checking in on the remaining titles – two of my all-time favorite Hammers – in the weeks ahead. A fifth box set, Death & Deceit, has been announced for March 23, featuring the more adventure-oriented titles Visa to Canton, The Pirates of Blood River, The Scarlet Blade, and The Brigand of Kandahar.