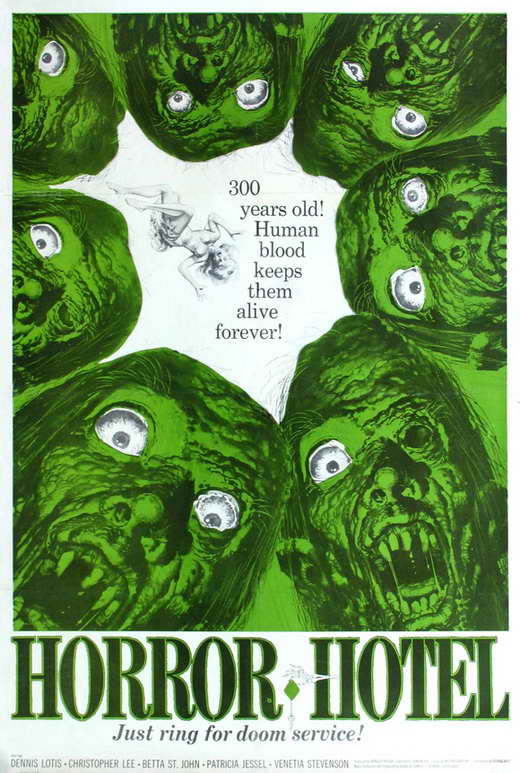

Just prior to establishing Amicus Productions, one of the major names in 60’s and 70’s horror, American producers Milton Subotsky and Max Rosenberg collaborated on a British film, The City of the Dead (1960), released in the States as Horror Hotel. Consider it proto-Amicus. This is an eerie little oddity, shot at Shepperton Studios in England with a mostly British cast donning American accents for a story set in Massachusetts. And it feels American, despite the prominent presence of ringer Christopher Lee – with its studio-bound, perpetually fog-engulfed sets, it has the atmosphere of a Roger Corman Gothic horror or a Twilight Zone. There’s also the shadow of Psycho (1960) hanging over it, given an uncanny similarity in plot construction between the films – though this appears to be nothing more than a fascinating coincidence since both films were in production at the same time. But perhaps we should be thinking of Mario Bava instead, since it begins in a historical flashback similar to the same year’s Black Sunday, with a witch being sentenced by a mob, before she comes back in the present day to wreak her revenge. In any event, The City of the Dead feels as if it were assembled from the parts of many horror products from the era, a summation of 1960 genre mood. Like the Amicus films that would follow, it’s also well made, pulling from dependable tropes and putting every effort into giving audiences their money’s worth.

Bill Maitland (Tom Naylor) stumbles through the ancient graveyard at Whitewood.

In Whitewood, Massachussetts, in 1692, Elizabeth Selwyn (Patricia Jessel) is burned at the stake while her co-conspirator in black magic, Jethrow Keane (Valentine Dyall, The Haunting), watches. The film flashes forward to Christopher Lee – fresh off his Hammer horror breakthrough – as Professor Alan Driscoll, teaching his students about the history of witches in New England. One of his pupils, the beautiful and intelligent Nan Barlow (Venetia Stevenson, daughter of director Robert Stevenson and actress Anna Lee), decides to travel to nearby Whitewood, where her family once lived, to write a paper on witchcraft. As she drives into a thick fog, she gives a lift to a gloomy-looking man standing at the side of the road who introduces himself as Keane. “To Whitehead, time stands still,” he warns her. When she parks in town, she turns to discover her passenger has disappeared – a lovely assimilation of campfire folklore. (When this occurs again later in the film, he has the wonderful Lynch-ian line, “To see me is a special privilege.”) She checks into Raven’s Inn, owned by the stern Mrs. Newless (Jessel again), and later meets Patricia (Betta St. John, Corridors of Blood), who has recently arrived in town to care for her blind grandfather, Reverend Russell (Norman MacOwan, X the Unknown). Patricia lets Nan borrow a book on devil worship from the antiquarian bookstore she’s taken over from her family. That night, while reading the book, Patricia hears a strange chanting. She discovers a passage into a cellar, where she’s assaulted by dark-robed cultists and placed on an altar under a sacrificial knife. Exit Nan, a la Janet Leigh/Marion Crane. Nan should have known something unnatural was afoot much earlier, partly because Lottie (Ann Beach), a mute servant girl, tried to warn her, and partly because of the hotel guests slow-dancing somberly late at night to jazz music.

Lobby card depicting Elizabeth Selwyn (Patricia Jessel) burning at the stake.

The second act follows Nan’s older brother Richard Barlow (Dennis Lotis, Sword of Sherwood Forest), a professor at the same college and witchcraft skeptic, searching for his missing sister after he meets up with a concerned Patricia. Professor Driscoll tries to assure Barlow that Nan will turn up eventually, but the audience has reason to distrust him: we witness him interrupted in the act of some black magic ritual, and also he’s Christopher Lee. While Barlow and Patricia explore Whitewood, Nan’s boyfriend Bill Maitland (Tom Naylor) also makes the journey, but his car spins out of control and crashes after the Whitewood fog throws visions of Elizabeth Selwyn at him. We soon learn that Selwyn and Keane have been arranging events in time for the witch’s sabbath; to sacrifice the Whitewood descendants will grant the witches more years of life.

The City of the Dead might be too-obviously a studio, that rolling fog not really disguising the fact, but that only adds to its atmosphere. Whitewood is supposed to feel like it exists in a claustrophobic alternate dimension, the road to which becomes a supernatural passage – I was reminded of John Carpenter’s In the Mouth of Madness (1994) and the Lovecraft stories that inspired it. The finale offers a satisfying bit of spectacle, with stabbings and chanting and cultists bursting into flame. It’s a solid groundwork for Amicus, efficiently offering the drive-in crowd everything they want to see – even Stevenson strips down, hilariously, into an impractically sexy teddy while changing clothes. (You’d think she has a date, to dress like that. She doesn’t.) Subotsky is credited with co-writing the screenplay with George Baxt, who wrote the same year’s Circus of Horrors and would go on to write The Shadow of the Cat (1961) for Hammer and the gloriously exploitative Tower of Evil (aka Horror on Snape Island, 1972). Director John Llewellyn Moxie would spend most of the rest of his career in television; among his many credits is The Night Stalker (1972). But the film is most invaluable to modern horror fans for its strong use of a young Christopher Lee, treating him as the horror icon he had just become. Lee chants his ritual incarnations as if he means every word. Maybe he did.