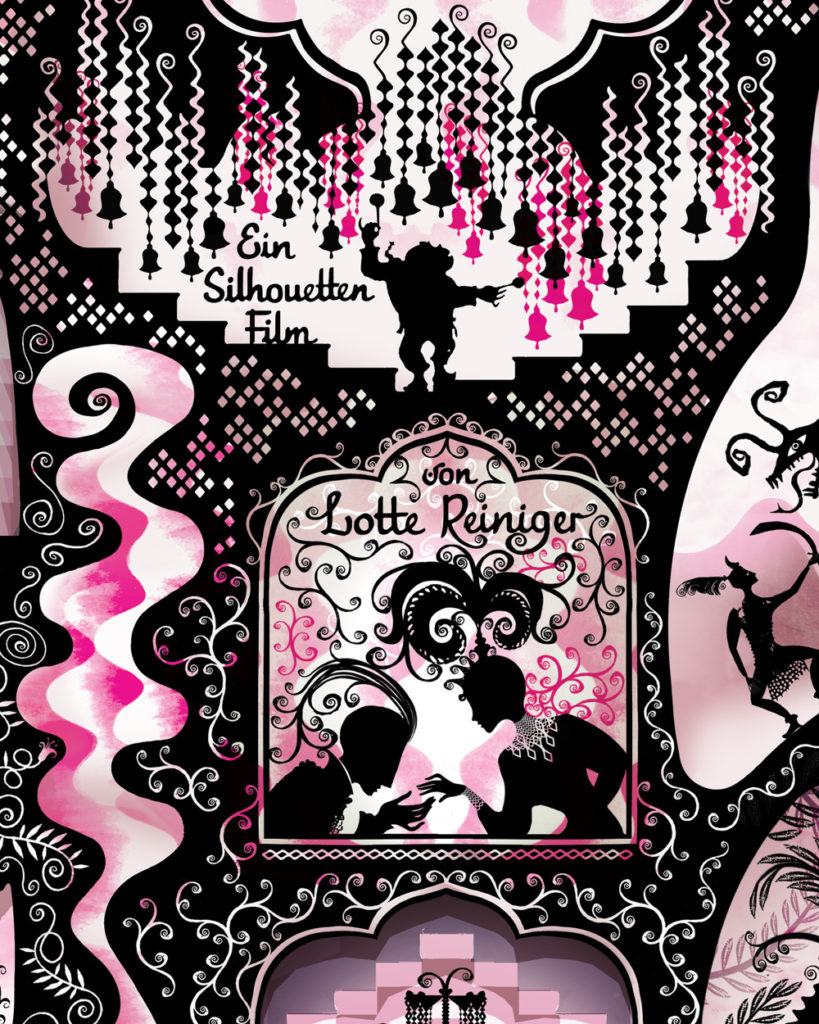

The opening caption of an English language import of one of animator Lotte Reiniger’s shorts, “The Adventures of Dr. Dolittle: The Lion’s Den” (1923), reads: “The characters in this little comedy have no real existence. They have been designed and cut out of a sheet of black paper and are made to move on backgrounds lit from below and photographed from above. This brief explanation is not offered as an apology for their lack of life but to make you marvel that they have so much.” Silhouette animation was the signature style of Reiniger, who at a young age enlisted with the Theater of Max Reinhardt and eventually began experimenting with animation, developing short films on the path to her first experimental feature-length film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). Watching this film today, it is a marvel that her two-dimension shadow puppets have so much life. The central characters, introduced one at a time at the top of the film, begin as fairy tale abstractions while we are drawn in by the delicate, intricate cuttings, the subtle integration of in-camera special effects, the elaborate backgrounds, and Reiniger’s confident mastery of her form. But by the end of the film, I was struck by how much I actually cared about these characters whose faces are never revealed except in profile – the finale emanates authentic tenderness as the silhouettes draw in close and merge for their romantic reconciliations. Reiniger wasn’t certain that a feature-length animated film could sustain an audience’s interest (the current restored version, available on Blu-ray from Milestone, is 67 minutes); the concerns would be echoed by critics of Disney over a decade later when he prepared to debut Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). Yet the film is entertaining throughout, gaining more dimensionality with each cliffhanger development. It’s a fine example of how cinema can draw audiences into a world of fantasy, even when using something as basic as paper cut-outs.

The fairy Pari Banou is introduced to the Caliph while Princess Dinarsade looks on.

Yet these seem like so much more. Reiniger’s imagination lets loose as the silhouettes are constantly in a state of Arabian Nights-style metamorphosis. She plants jokes in details big – like Ahmed escaping a snake pit by using the snake as a climbing rope – or small – like Pari Banou’s absurd high heels (above). She finds comedy in the jealous in-fighting triggered when Ahmed stumbles into a secret harem, or in the evil magician’s transformation first into a bat and then – not all at once, but lazily limb by limb – a kangaroo. Most importantly, she achieves a great deal of expression using these figures, from the sensuality of Pari Banou and her fairy companions discarding their feathers to bathe in a pool in the forest, or the rapture Achmed feels when he holds his love in his arms. The story is an Orientalism pastiche drawing primarily from two tales, “The Story of Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Pari Banou” and “The Story of Aladdin, or the Wonderful Lamp,” with certain elements flown in from others. Divided into five acts, each segment, though a part of a bigger story, feels like a separate Arabian Nights episode, as though an off-screen Scheherazade might be telling the story in segments, one night at a time, holding your interest captive.

Aladin and his magic lamp.

An African magician sets his eyes on Princess Dinarsade (in the Nights, Dinarzade was Scheherazade’s sister). Creating a flying horse out of an oily mist, he shows it off for the Caliph but refuses to sell for any price. The Caliph promises any of his treasures – so the magician chooses the princess, to the Caliph’s dismay. The magician then offers Prince Achmed an opportunity to ride the horse, but it immediately carries him into the sky. The Caliph arrests the magician, and Achmed sets off on his adventures, first in the “magic islands of Wak-Wak,” where he meets and steals Pari Banou, and then, after the magician kidnaps her, into China where she’s been sold to the emperor. When Pari Banou is kidnapped again, this time by the flying demons of Wak-Wak, Achmed cannot gain access to that hidden kingdom until he possesses the magic lamp of Aladin [sic]. He quickly finds Aladin, rescuing him from a monster, but he no longer has the lamp; this leads to a story-within-our-story as Aladin tells his own tale, which should be familiar to most everyone. Eventually it’s determined that the magician has been tormenting Aladin just as he has been Achmed, taking the lamp from him and keeping him from Aladin’s true love, Princess Dinarsade. They enlist the aid of the magician’s arch nemesis, the Witch of the Flaming Mountain, to vanquish the African sorcerer; the lamp in hand, a climactic assault on Wak-Wak ensues. The most striking moment of the final battle comes when Achmed battles a hydra-like creature which sprouts a new head for each that Achmed severs. The Witch solves the problem by cauterizing the stumps with the flame of the magic lamp.

The Chinese emperor courts Pari Banou.

Begun in 1923 and completed three years later, Reiniger’s film, made with fellow avant-garde artists Walter Ruttmann (Berlin: Symphony of a Metropolis), Berthold Bartosch, and Reiniger’s husband Carl Koch, innovated animation techniques including using layers of glass to create an illusion of depth, a technique later built upon by Walt Disney with the multi-plane camera. The film was championed in France, notably by Jean Renoir, who called it a masterpiece. Reiniger and Koch fled Germany as the Nazis rose to power, and after working abroad in England and Italy they would reluctantly return in 1944 to care for Reiniger’s sick mother. They returned to England after the war and established Primrose Productions, creating silhouette animated shorts with narration, including cut-down bits from Prince Achmed. Though she took a break from animating following Koch’s death in 1963, in her later years Reiniger continued work in animation as well as lecturing and instruction until her death in 1981. The enduring appeal of Prince Achmed is its endless wit and surprise, like a magic puzzle box that keeps unfolding before you in unexpected directions. After Prince Achmed, anything seemed possible for animated feature films.