So much in Mario Bava’s masterful Hitchcock riff The Girl Who Knew Too Much (aka Evil Eye, 1963) relies upon the luminous, feline features of Letícia Román. Bava puts his heroine through the ringer, but often stays close to her face, occasionally cutting in close to eyes that widen in curiosity or terror, by turns. Román, the audience surrogate, is a mystery buff thrust into a world in which any given event may or may not be real; in critical moments Bava shoots her perspective through a watery distortion so that we also have reason to doubt. We first meet her character, an American tourist named Nora, on a plane en route to Rome. The AIP Evil Eye cut of the film gives her a clever introduction unique from the Italian version: Bava lets his camera drift from one passenger to another down the aisle, eavesdropping on their thoughts (one in untranslated Italian) before settling on Nora, who’s dwelling on a murder. A quick pan down to her reading material – The Knife, which appears to be a giallo – allows us to understand that the crime in which she’s complicit is purely fictional. A fellow passenger offers her a cigarette, and in the next scene he’s getting arrested in the airport for trafficking marijuana cigarettes; Nora discreetly tries to lose the pack of them that he gave her but is thwarted when a passer-by tells her she dropped something. This pays off in a funny gag that ends the Italian cut of the film, as Nora realizes she’s been smoking them through the whole movie – and wonders if everything she’s witnessed is a drug-induced hallucination. It’s an unconvincing argument, but on point: she is, after all, an enthusiast of Agatha Christie and Edgar Wallace, so couldn’t she be writing her own pulp paperback? One of the reasons Bava’s film is so fun is that it’s a black-and-white thriller about these kinds of black-and-white thrillers, which were so common in the wake of Les diaboliques (1955) and Psycho (1960). Nora isn’t just reacting to the terrible events that have occurred; she’s also remembering what investigative steps to take, and fearing she’s not the protagonist at all, but merely the next victim on the murderer’s list.

A murder, or a vision of a murder from the past, or just Nora’s imagination?

Shortly after arriving at the home of her bedridden Aunt Ethel (Chana Coubert), Ethel passes away – while Nora is watching, her shock mirrored in the hissing reaction of a cat. The lights flash on and off as though something supernatural has occurred, and indeed, this is the moment of the film that is closest to the eerie gothic horror mode to which Bava had contributed so strongly with Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio, 1960), while in several details directly anticipating the episode “The Drop of Water” from his 1963 portmanteau Black Sabbath (I tre volte della paura). If this feels, like “The Drop of Water,” to be a short film within the film, that might be because it’s also a red herring. Aunt Ethel’s death serves no greater purpose than to get the terrified Nora running out into the street and to the Piazza di Spagna, where she is promptly mugged (also irrelevant), and awakens from a faint or concussion to see a screaming woman collapse on the street and a man pull a knife from her back and drag her off. The rapid succession of traumas sends Nora reeling, until she finally regains her footing and tries to prove both to the police and her friend Marcello (John Saxon, lively and funny) that the murder really occurred, despite the complete absence of evidence. There’s the troublesome detail that the murder as she describes it is an exact match for a crime from 10 years prior, a killer never caught who was apparently choosing victims by working through the alphabet (as in Agatha Christie’s The ABC Murders). Did Nora have a psychic vision of the past? She receives a mysterious phone call from a stranger who speculates she might be the next victim, since her last name (different depending on what cut you’re watching) starts with a “D” – the next in line if the killings resume. She tries to think like a detective from one of her stories, scattering talcum powder on the passage leading to her bedroom so she can catch the footprints of intruders, then lacing up a spider web of strings to be triggered if the door is opened – a wonderful image that makes her look not like a spider but a fly already paralyzed in its trap.

Something familiar, not quite placed: Nora (Letícia Román) investigates a possible clue.

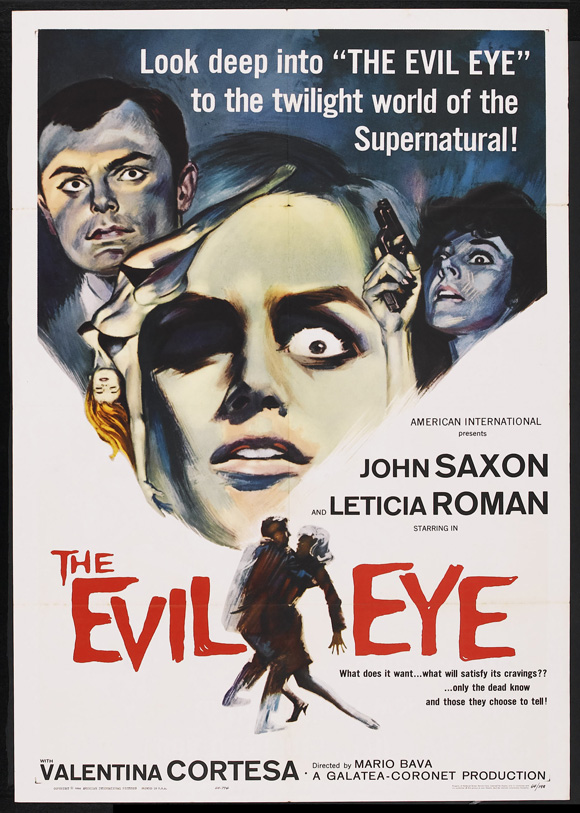

The mystery – which also takes into account characters played by Valentina Cortese (Day for Night), Dante DiPaolo (Seven Brides for Seven Brothers), and Titti Tomaino – is a satisfying one, but throughout Bava dazzles, whether through gorgeously photographed looming shadows and blinding-bright lights, elegantly choreographed trips through the streets and sights of Rome, or witty, unexpected transitions. An example of the latter comes at the end of a tension-filled journey into an empty apartment where Nora has been lured by a threatening voice (or a typewriter, if you’re watching the AIP version). After being joined by Marcello, the two gather close to the reel-to-reel recorder from which Nora says she heard the voice. They rewind and play it back, only to hear the film’s theme song, Adriano Celentano singing “Furore,” played at peak volume and squealing speed; both jump just as the viewer probably does, and Bava hard cuts to the two back home, again investigating the recorder in less disconcerting surroundings. Another winking edit occurs only in the Italian version: while sunbathing on the beach in a revealing bikini, Nora becomes concerned about the increasingly hostile looks from Marcello. He corners her and we see the fear in her eyes – is he the killer? – before, overcome with sexual desire, he kisses her; Bava then cuts to the two of them sharing the same passionate kiss elsewhere, delighted at the end of a long day together, as if, to Nora, fear and sexual excitement have become interchangeable in her new, pulp thriller lifestyle. In the film’s climax, a figure’s death is signaled by their dropping out of frame, revealing gunshot holes in the door behind them, illuminated with bright beams of light cutting through the smoke. The emphasis on style and self-contained suspense setpieces paved the way for the giallo genre which would later dominate Italian cinemas; for now, improbably, this perfect entertainment was (and would remain) Bava’s lowest grossing film.