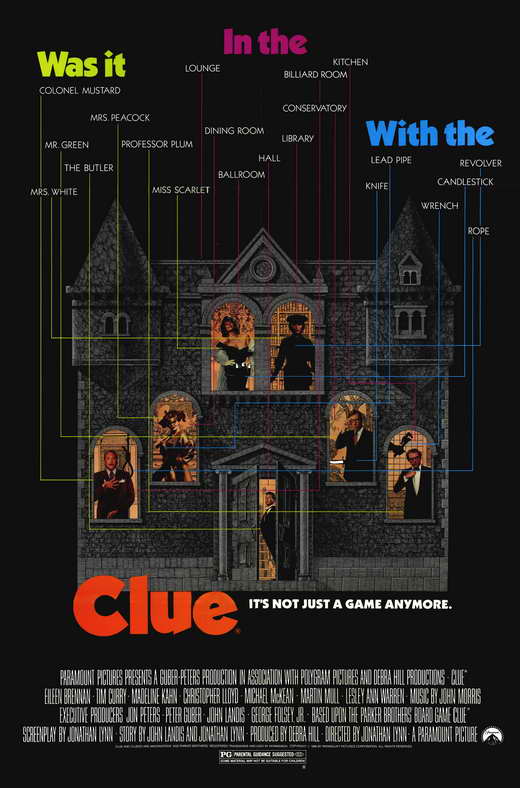

In recent years we’ve had intermittent threats of board games becoming movies. Candy Man and Monopoly have been in development for a long while, the latter most recently announced with Kevin Hart attached. Yet this has been an intellectual property avenue that’s largely, perhaps mercifully, been neglected. Battleship (2012) may be one of the genre’s most prominent examples, thanks to its absurdity: changing the simple strategy game into an alien invasion epic. The genre also includes horror films – Ouija (2014) and Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016), from Hasbro Studios – and, if role-playing games count, Dungeons & Dragons (2000). (1995’s Jumanji may be an honorable mention, but it’s actually based on a children’s book.) It makes sense that the more narrative-friendly medium of video games are adapted far more frequently, though doing that well has also proven a notorious challenge. For board game movies, it may just be that we’ll never top Clue (1985). Even when Clue was released, many critics were cynical of the idea, and it wasn’t immediately hailed as anything special. It may be that its central gimmick was too great a distraction: the film was released with three different endings, so unless the theater announced which ending it was showing (and many of my local theaters did), you were essentially partaking in a game of chance to find out how it would end. When the film was released on VHS, it took a shape which has subsequently become its standard cut – all endings included – making it clear that not only was one ending was quite a bit better than the others, but that you’d feel robbed if you didn’t get to see all of them. Wouldn’t you think just a bit less of the movie if it didn’t have Michael McKean’s final triumphant line, or Madeline Kahn’s constipated description about hating someone so much that “it, flame, flame, flames, on the side of my face, breathing breaths, heaving breaths…” Watching all of its endings in a row, we can also see how they’re intended to comically rhyme with one another, and that it was always meant that viewers seek them all out. As a complete package, the film has deservedly become a classic of 80’s comedy.

The candlestick.

That the film works so well can only be marginally attributed to the source material. The game Clue (original UK name: Cluedo) is of course a whodunit, so making a murder-mystery was a given. The 70’s version that my family owned when I was growing up depicted actors/models on the cover portraying the famous characters, which further suggests a live-action interpretation could easily be made. But the film’s success relies on its slam-dunk creative team and cast. John Landis (An American Werewolf in London, Trading Places, etc.), who executive produced, conceived the story with the film’s director Jonathan Lynn, and Lynn wrote the extremely verbose screenplay. Lynn was steeped in the British comedy scene of the 60’s as both actor and writer, having appeared in Cambridge Circus, and eventually went on to co-write the popular Yes Minister series. Clue was his first directorial effort; he would go on to make Nuns on the Run (1990) and My Cousin Vinny (1992), among others. The cast is filled out with ringers. In addition to Kahn as Mrs. White and McKean as Mr. Green, we’re served up Eileen Brennan as Mrs. Peacock, Christopher Lloyd as Professor Plum, Martin Mull as Colonel Mustard, Lesley Ann Warren as Miss Scarlet, and a couple of new characters: Tim Curry as the Butler and Colleen Camp as French maid Yvette. (Lee Ving of Flashdance also appears, however briefly, as Mr. Boddy.) The setting is a sprawling mansion with rooms and murder weapons paying homage to the board game; even the floor has a grid-like pattern that suggests spaces on a board. The location provides the opportunity for Lynn and Landis to riff on the Old Dark House mystery-horror-comedy genre so popular in the 20’s and 30’s (The Cat and the Canary and its ilk) as well as Agatha Christie including her long-running play The Mousetrap. Clue wasn’t the only 80’s film to mine this territory, but evoking these tropes provides a warmly familiar backdrop for a comedy in which how the actors react to each other is far more important than who actually dun-it.

Amateur investigations with Colleen Camp, Lesley Ann Warren, Michael McKean, Tim Curry, Christopher Lloyd, Martin Mull, and Madeline Kahn.

Lynn’s screenplay continually divides up, pairs off, and chaotically mashes together his characters so that in each new combination, every performer has a chance to shine in different ways. Warren’s devil-may-care Miss Scarlet is the madam of a politically-connected escort service. Lloyd’s Prof. Plum is a handsy lech – the polar opposite of his role in the same year’s Back to the Future. Kahn is a black widow with multiple dead or missing husbands:

“Your first husband also disappeared.”

“That was his job. He was an illusionist.”

“But he never reappeared.”

“He wasn’t a very good illusionist.”

McKean’s character is highly strung. Curry is a Butler’s Butler; when he suggests they move the cook’s body from the kitchen into the study, it’s just to keep the kitchen tidy. Mrs. Peacock is dignified but oblivious:

“Is there a little girl’s room in the hall?”

“Oui oui, Madame.”

“No, I just want to powder my nose.”

With Mr. Boddy (Lee Ving).

And so on. Nothing they do very much matters – we know that the plot must be constructed in such a way that the culprit could be literally anyone (isn’t this true of all those murder mysteries that don’t play fair?). Instead, the focus is on building a comic momentum. The film revs up slowly, its jokes patiently deployed, until bodies start piling up, panic sets in, and the comedy reaches a breathless crescendo in the film’s most fondly remembered set piece, Curry’s attempt to solve the murders by verbally and physically recapping everything that’s happened in the film so far, sprinting from room to room and playing both killer and victim. (Let’s be honest. Even in this intimidating ensemble, Curry is the film’s real star.) That Lynn is willing to go as broad as Mel Brooks with this material is indicated early on, not just from the recurring bit of guests at the front door sniffing the air suspiciously and checking their shoes, but at the generously spilling cleavage from Camp and Warren. This is proudly unsophisticated comedy. The jokes may not all be good, but like Airplane! they pummel you into submission through sheer accumulation. That’s how we get to the multiple endings, which work best when presented as multiple endings, so that we can see the various ways this could play out, like Penn and Teller revealing how a magic trick works. When viewed one after another, the endings are funnier, players shifted just slightly to present new murderers and motives, similar lines given multiple meanings, all of it wonderfully weightless. (I could not tell you what the plot of this film is, nor any of its plots, except that blackmail and politics and a mysterious phone call from J. Edgar Hoover are involved.) Clue is, indeed, a delightfully played game, which is a lesson that any future board game-to-film should try to remember.