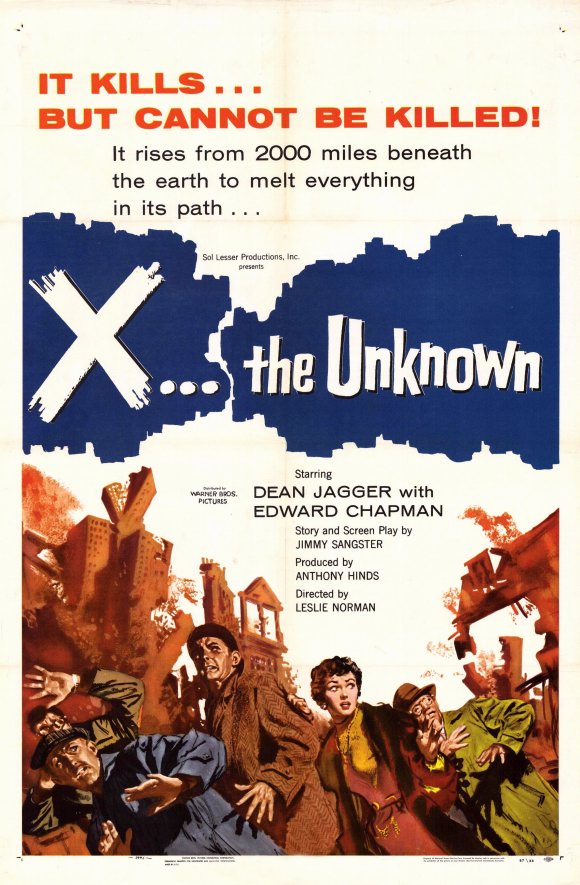

When Hammer released 1955’s The Quatermass Xperiment, the emphasized X of the title served to proudly display the X certificate it received from the British Board of Film Censors. Limiting the audience to those over 16 would not be an impediment, but a sensational selling point. When the film became a smash hit – launching Hammer horror, albeit in a science fiction vein – it shouldn’t be a surprise that the expedited follow-up was called X the Unknown (1956), in true exploitation fashion. This wasn’t a proper sequel: writer Nigel Kneale wouldn’t grant Hammer the rights to insert his Professor Quatermass creation into their independently developed story. Kneale was still stinging a bit after their casting of Brian Donlevy as Quatermass, which turned the inquisitive, calculating, and distinctly British character into a brash American barking orders at his troops. (Kneale would return to the Hammer fold in 1957 for Quatermass 2 and The Abominable Snowman, when given the opportunity to write those screenplays himself.) Though Donlevy doesn’t appear in X the Unknown, a Hollywood actor was again cast in the lead: Dean Jagger (White Christmas, Twelve O’clock High), brought in, like Donlevy, to secure the film’s distribution in the U.S. Jagger would play Dr. Adam Royston, a nuclear scientist whose experiments become the source of both awe and scorn throughout the film. Like Quatermass, he investigates a fast-developing menace that defies known science; unlike Donlevy, his character’s demeanor is appealingly empathetic. He’s painfully aware of the human cost of his field of study, and recognizes in this new radioactive threat – emerging from beneath the Earth’s crust – a parallel to the nuclear horror unleashed at the close of the last great war.

Face-melting horror.

The Quatermass Xperiment template is followed pretty closely, but screenwriter Jimmy Sangster, about to become a Hammer MVP with the screenplays for The Curse of Frankenstein (1957) and Dracula (1958), cleverly inverts the alien invasion formula by having the threat be entirely native. As British soldiers (including pop star Anthony Newley) practice using a Geiger counter in a muddy field, the level of radiation spikes and the earth splits open, one of the men consumed by an unseen force, another becoming badly burned by radiation. Dr. Royston is enlisted to help, but the case only turns more mysterious when a staffer in a local hospital’s radiation laboratory has his face melted away, in a very impressive and grotesque special effect that is all the more disturbing for a brief shot of his finger swelling to burst. (The X certificate, in this case, is earned.) Royston teams up with the Atomic Energy Commission’s “Mac” McGill, played by the always-welcome Leo McKern. Together they begin to realize that the thing they seek, which has the physical appearance of mud, actually absorbs radiation, seeking it out and consuming it while becoming more and more powerful. The climax essentially turns the film into The Blob, two years ahead of that film’s release, as the mud-creature oozes across the countryside, threatening a village as it seeks larger sources of radioactivity to devour. Incidentally, there’s so much radiation handling, so much Geiger counter static, radiation scars, and lack of radiation suits that this film may actually give you radiation sickness. If you’ve recently watched the miniseries Chernobyl, prepare for this film to give you a lot more anxiety than it originally intended.

A jeep becomes stuck while trying to lure the radioactive menace.

X the Unknown is directed by Leslie Norman, replacing the blacklisted expat Joseph Losey, who left the film reportedly due to pneumonia (but more likely because of McCarthy supporter Jagger). Losey would go on to direct a different radiation-drenched movie for Hammer, The Damned (1963) – which I’ll be visiting shortly for this site. I had only seen X the Unknown once before, on an inferior DVD presentation whose glitches were so distracting that I couldn’t engage with the film. Therefore the new Shout Factory Blu-ray is especially welcome. The black and white photography on display is beautiful, especially in a nighttime scene in which two boys run through a shadowy forest before one meets his unfortunate fate. Part of what makes this film so affecting is that Sangster then follows up with the boy’s fate, in a hospital where he perishes from his radiation exposure, his father angrily confronting Royston as a scapegoat for all atomic scientists. Royston says nothing, but steels himself to his cause, giving his eventual victory a cathartic charge. Of course the number of 50’s movies grappling with the horrific possibilities of nuclear experimentation is endless, but this would make an interesting pairing with, if not The Damned, then Godzilla (1954), the first and most somber of Toho’s series. The brief, startling gore effects clearly mark this as a transitional film into Curse of Frankenstein and Hammer’s bloody gothics to come, but X the Unknown stands apart as a uniquely compelling thriller now that we can view it afresh.