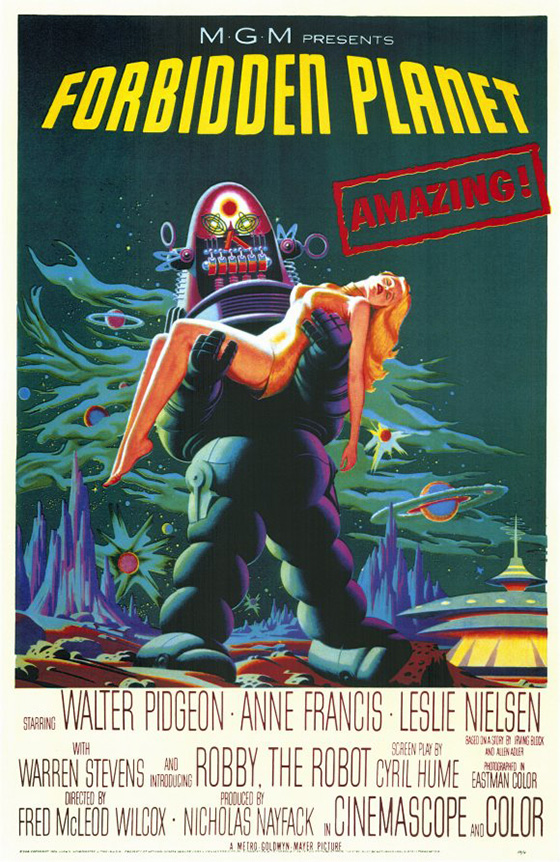

Forbidden Planet (1956) is still an effectively scary film. I know this because I just started playing excerpts from the film’s all-electronic score through iTunes, and my dogs became alarmed and ran out of the room barking. The “music” – electronic squeals and squawks and pulsating booms by innovators Louis and Bebe Barron – is very important in this movie, because it sounds like no other science fiction film of its era, granting it an eerie, anomalous quality which would be absent from the genre until 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Of course the nearest equivalent would be the theremin, used in several SF films of the 50’s including Bernard Herrmann’s score for The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), but at least the theremin is musical. The Barrons, using circuitry of their own design, assault the viewer with their cosmic sound design (or “electronic tonalities,” as the credits describe), so as the imposing words Forbidden Planet stretch across the screen and the opening theme comes at you, you know you’re in for something special. It’s enough to make you forgive the much more conventional opening narration that sets the scene and sounds like every film since Rocketship X-M (1950), or the rather bland interior of the spaceship C-57D, and its blander crew of white men in bland gray uniforms. But their ship is a flying saucer, a neat reversal of 50’s iconography, and the mystery which confronts them – they are searching for a lost ship, the Bellerophon, and as they approach the planet where it was last sent, Altair IV, the man who hails them on the radio asks them to turn around and leave immediately – is a taut set-up, even if, a decade later, it might be a typical Star Trek plot. As the story progresses, the film also anticipates Alien (1979) as the crew struggles to mount an adequate defense against a relentless invisible monster. It’s a creepy film, but creepier still is the revelation of just what that monster is – a “monster from the Id.”

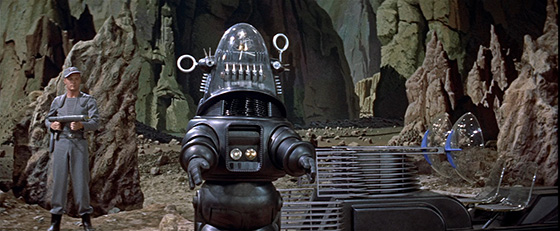

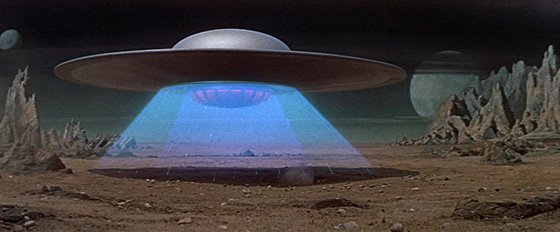

The C-57D lands on Altair IV.

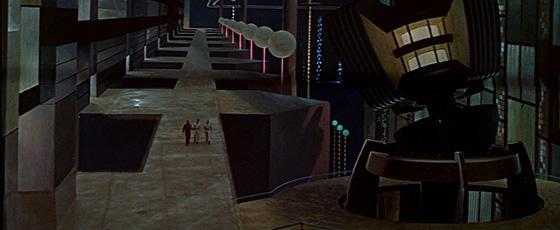

The intellectual thrust of the story, and its general scientific (and psychological, and anthropological) curiosity, makes Forbidden Planet feel like a compelling 50’s science fiction paperback. One of the things I always find refreshing about the film is that even though the message is ultimately cautionary regarding scientific advancement – this was the age of the atomic bomb, after all – a great deal of time is spent investigating the discoveries of stranded scientist Dr. Morbius (Walter Pidgeon, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea) regarding the planet’s ancient civilization called the Krell. The Krell achieved mind-blowing scientific advances in their vast city, although all that remains is buried underground, stretching for miles in vertiginous matte paintings which are still appealingly evocative. The Krell themselves were wiped out – and by what is something which soon becomes of prime importance to Commander Adams (Leslie Nielsen, long before Airplane! and Police Squad! made him a comedy icon), since it may have something to do with the creature that’s stalking and attacking his crew every night. The haughty Morbius has spent years exploring and researching the Krell city, even risking his life (or so he claims) boosting his IQ with a Krell device which projects images from his mind. He makes it clear that only he can use the machine – it would be lethal for the lesser intellects of Adams and Lieutenant Ostrow (Warren Stevens, The Time Tunnel). Meanwhile, the crew of the C-57D marvels at Morbius’s creation Robby the Robot, which can replicate any artifact like a next-generation 3-D printer, though Cook (Earl Holliman) just wants Robby to make him more whiskey. “It’s smooth!” he applauds Robby. Also, there’s no hangover.

Altaira (Anne Francis) takes a swim.

The crew is equally transfixed by Morbius’s comely, miniskirted daughter Altaira (Anne Francis, Honey West), who has never met a man other than her father, and is just as fascinated with them as they are with her. After one wolfish member of the crew teaches her about kissing, she’s soon kissing every last one of her visitors, though it’s only the resistant Commander Adams who ultimately provides the sought-after “stimulation.” Forbidden Planet almost suggests the kind of free love that would be promoted in Robert Heinlein’s novel Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) and, of course, would be a hot topic in the 60’s with the rise of “the pill,” Haight-Ashbury, etc. Anne Francis is wonderful in the film, antithesis to the female in most 50’s SF movies (the woman scientist who bends a knee to the square-jawed male protagonist); although she’s an innocent regarding sex, she also shares her father’s appreciation for the scientific method, and is quick to apply it. She’s outraged when Commander Adams suggests the crew is taking advantage of her, or that she should dress more properly (she designed and made her clothes herself, she retorts). In many ways she’s a modern woman, and if she ultimately ends up with Adams, it’s less a Taming of the Shrew situation than Adams simply learning to be a bit more open-minded – and honest with his own sexuality. Am I reading too much into this? Then let me just say that Anne Francis defiantly skinny dips (in a flesh-colored bodysuit) and plays with a live tiger. She’s fun.

The invisible Monster from the Id is revealed when caught in a force field.

Forbidden Planet had a major advantage over its competitors in that it was a big budgeted MGM film – you could almost call it a prestige picture, produced on a scale rare for a genre film of its day. Apart from the spectacular visuals in the abandoned Krell city (the platforms over bottomless pits would be recreated in Star Wars, as would the hologram-like miniature of Altaira conjured by Morbius in the projection machine), it’s hard not to appreciate the use of animation in the film, from Joshua Meador, on loan from Walt Disney Studios. Every ray gun blast and laser beam is animated, granting a distinctive character to the film. Highly memorable is the “appearance” of the “Id Monster,” invisible until it becomes trapped in the force field erected outside the ship. The two-legged, taloned, fanged, and bull-like creature is shown in red outline as it rages and gnashes. The creature is the manifestation of Dr. Morbius’ subconscious, his jealous and sinister dark side, and is given an appropriately evil and beastly shape. Robby the Robot is the runaway star of the film, however. The expensive prop, with its visible circuitry and switches, rotating discs, and impeccable manners, has far more personality than other robots of its day – I’m looking at you, Gog. Robby would go on to appear in other films (The Invisible Boy, Gremlins) and TV, and remains one of the most iconic robots of all time. He’s easily one of the most likeable characters in the film, even if the famous poster art has him menacingly carrying an unconscious Anne Francis in imitation of the poster for The Day the Earth Stood Still. Google, mobile devices, and Amazon drones be damned, everyone still needs their own Robby. I mean, we don’t have minibars in our homes anymore, and Amazon’s not mixing you any drinks.

The Krell underground city.

When Stanley Kubrick approached Arthur C. Clarke to write 2001, he said they needed to make it because there weren’t any great science fiction films. Although Kubrick’s film would be testament to what he meant by that, I would submit Forbidden Planet to refute the argument. Here is a film that used the acceptable SF template of its time – white guys in a rocketship, a cold-hearted scientist, and a pretty girl vs. an alien menace – and significantly advanced the language and concepts in the storytelling. The electronic, atonal score rejected schmaltz and delivered something genuinely futuristic and alien. The storyline – as many have pointed out, modeled roughly on The Tempest with Dr. Morbius in the Prospero role and Altaira his Miranda, Robby his Ariel – is not just sophisticated but presents science fiction as it ought to be: an exploration of ideas with hungry curiosity, a lack of bias (see the open-minded depiction of female sexuality), and the radical notion that the evil alien invader might not come from Mars or Venus but our own selves. We are the enemy – not just our bodies, as replicated and replaced in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) – but what lurks in the deep dark recesses of our minds. Of course there are many good SF films pre-2001, but Forbidden Planet set a very high standard that reminded what the genre could really do.