First Men in the Moon (1964), an adaptation of the 1901 novel by H.G. Wells, presented Ray Harryhausen with the opportunity to return to science fiction following a visit to Greek mythology in the career-best Jason and the Argonauts (1963). One could argue he had been absent from the genre for longer than that: Mysterious Island (1961), though ostensibly a work of science fiction, leans harder on elements of fantasy adventure like his prior films The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960) and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958). With the powers of Cavorite, Harryhausen now breaks free of the Earth’s gravitational pull and heads for the Moon to uncover the secret underground city of the Selenites. (All right, perhaps there’s a good deal of fantasy adventure here too.) The film reunited Harryhausen with two recurring collaborators: producer Charles H. Schneer, who had worked with him since It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955), and director Nathan Juran of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and 2o Million Miles to Earth (1957). Absent, unfortunately, was composer Bernard Herrmann, though Laurie Anderson of the TV series The Avengers ably fills in. The screenplay was co-authored by Nigel Kneale, famous for creating Professor Quatermass; Kneale’s classic script for Quatermass and the Pit (1967) seems to borrow a few ideas from Wells and his Selenites. Really the only thing which seems a bit out of place is the infrequent use of stop-motion animation. We are an hour and twelve minutes into the film before the first stop-motion creation appears – the Mooncalf, a caterpillar-like creature with pincers which the Selenites put down with a laser gun. But except in certain brief shots, the Selenites themselves are not stop-motion, but actors in occasionally shoddy-looking costumes.

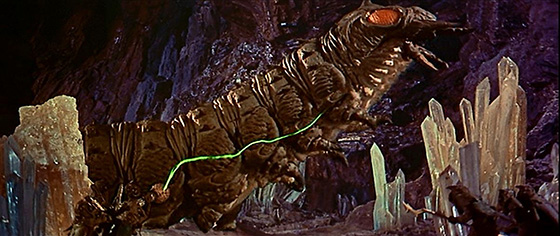

A Mooncalf, on a rampage, is zapped by Selenites.

It’s easy to see why the decision was made to present so many scenes with the Selenites as costumed actors: it was difficult enough for Harryhausen to animate seven living skeletons at once in Jason and the Argonauts; imagine trying to populate a city of aliens by the same method. Harryhausen has stated as much; in his Film Fantasy Scrapbook (1981) he wrote, “I have never been an advocate of ‘men in suits’ to represent animaloid creatures, but with our project the script called for masses of insect-like beings swarming over the Space Sphere. To avoid an eternity in animating the creatures en masse, I found it necessary to build insect suits in which we placed small children.” But that was not the only reason that stop motion is scarce in First Men in the Moon. Columbia insisted the film be shot in widescreen Panavision, for which Harryhausen had not adapted his “Dynamation” process. The time spent trying to make his animation work for widescreen meant sacrificing some of the planned FX sequences. He writes in An Animated Life (2003), “Among the lost sequences was a scene in which the scientists are ‘put to sleep’ and stored for when next they are required. The sequence would have shown them being ‘filed away’ by a machine that raised each Selenite up to its own hexagonal honeycomb-like chamber.” Nonetheless, the effects sequences which survive have the usual Harryhausen awe. The awe is perhaps amplified by the amount of time it takes to reach the Moon and finally encounter the fantastic. In particular I admire the moment when our proto-astronauts stumble across a massive metallic dome in the surface of the Moon, which opens slowly with the promise of an alien civilization below. The light slapstick comedy of the film’s Victorian-themed first half has come to an abrupt end, and now we are confronted with the potentially hostile unknown. It’s Harryhausen’s homage to the gates that lead to the interior jungle of Skull Island in King Kong (1933).

The astronauts discover an entrance to the underground Selenite city.

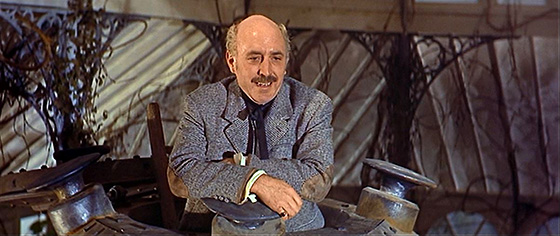

By 1964, Wells’ novel was six decades old, the science was dusty, and the space race was setting its sights on a real lunar landing. When presented with this challenge, Nigel Kneale had a clever conceit for his adaptation: he would set his prologue in the present day and show humans setting foot on the moon for “the first time.” Then he would wittily undercut the achievement with the discovery a British flag awaiting the astronauts on a moon rock. (Something similar, albeit considerably more surreal, is used at the start of Karel Zeman’s wonderful 1961 film The Fabulous Baron Munchausen.) Evidence discovered on the Moon leads investigators to track down Englishman Arnold Bedford (Edward Judd, The Day the Earth Caught Fire), now in a nursing home, but eager to recount the first actual voyage to the Moon. The film can then take place in an extended flashback, in 1899 – which feels thematically appropriate since so many Wells, Jules Verne, and other Victorian-era fantasies are recounted via a framing device and a first-person account of events that have already transpired. Bedford, in deep debt, attaches himself to Joseph Cavor (Lionel Jeffries, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang), a scientist whom everyone believes is a crackpot, but who has just invented an anti-gravity substance which he calls Cavorite – and which can be painted onto any object to make it launch into the air. Bedford hopes to make a fortune off his investment in the discovery, though his fiancée Kate Callender (Martha Hyer, Some Came Running) is skeptical, and Cavor is more interested in a trip to the Moon than making money. The premise is that different panels painted with the Cavorite will draw the “Sphere” capsule toward the gravitational pulls of either the Moon, the Earth, or the Sun. Bedford finally agrees to Cavor’s plans, and when Kate stumbles into the site of the launch, placing herself in immediate danger, she’s hastily pulled aboard.

Lionel Jeffries as Joseph Cavor, inventor of Cavorite.

Although the film’s first half places a bit too much emphasis on exaggerated comedy (see 1959’s Journey to the Center of the Earth for a much better balance of a similar formula), there’s still some charm in the film’s deliberately smash-bang approach to its steampunk scientific exploration. We don’t see Cavor trying to make the complex trajectory calculations to land his craft on the Moon, and when it comes to the problem of lack of oxygen, Cavor settles on diving suits. The launch and extremely violent crash on the Moon’s surface (softened only somewhat by opening those panels which reach back out toward the Earth’s gravity – er, somehow) are dealt with by grabbing tight to hammocks that dangle from the ceiling. The Sphere rolls for a good distance until it collides with some rocks, and Cavor, Bedford, and Kate are sprawled out unconscious. Good show! But by far, the back half of the film is the most interesting, as the tone darkens somewhat. Cavor grows increasingly frustrated at the Colonialist instincts of Bedford and Kate (she insists they bring an elephant gun to the Moon), and tries – and fails – to halt any violence between the explorers and the Selenites. This culminates in a scene in which he explains the concept of war to the “Grand Lunar,” who is understandably perturbed. Cavor would prefer to stay among the Selenites, and does so after we’re treated to an extended journey through the honeycomb-like caverns decorated with towering crystals, and with mineral-based technology that, at one point, acts as an X-ray on Kate so we can see her as another of Harryhausen’s trademark skeletons. If the film still seems a little short on Harryhausen-ness, at least it is infused with the spirit of H.G. Wells. Bedford and Kate’s desperate escape from the lunar kingdom recalls the escape from the Morlocks at the end of The Time Machine (in particular the 1960 adaptation), and a final twist borrows from The War of the Worlds, with a wink.