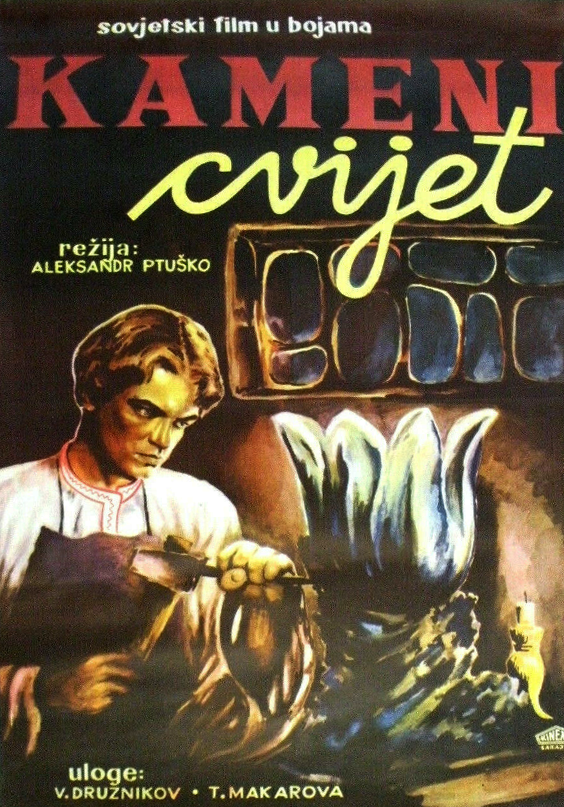

Soviet cinema’s master fantasist, Aleksandr Ptushko, forged the path that would make his reputation following a forced hiatus from filmmaking during WWII. He had previously supervised the production of a number of stop-motion shorts for Mosfilm as well as directed two groundbreaking features – a Communist-parable take on Jonathan Swift, The New Gulliver (1935), and The Golden Key (1939), based on the Pinocchio-inspired book by Aleksey Tolstoy – which combined live action with puppet animation in the style of George Pal’s Puppetoons. Returning to Moscow after the war, he set upon making a completely live action film in full color, using equipment and Agfa colored film stock seized from Germany. The Stone Flower (1946) was shot partially in the grand spaces of Prague’s Barrandov studio for its adaptation of a Pavel Bazhov story, an old folk tale from the Urals. It would be a children’s film of exceptional technical accomplishment, a cinematic illustrated storybook of which any random film frame could be hung on a wall. The film would go on to win a special prize for color at the first Cannes Film Festival, and become a big enough hit at home to set a new standard for Russian children’s cinema and launch Ptushko on a path that would take him to such dazzling fairy tale features as Sadko (1952), Ilya Muromets (1959), and many more up through his final feature, the sublime Ruslan and Ludmila (1972).

The Mistress of the Copper Mountain spies upon young Danilo (V. Kravchenko).

The film takes place in the recent past (“about 60 years ago in the old Urals factories”) and concerns the carving of the green copper mineral malachite – a color which Ptushko exploits frequently in the presence of magic. The factory workers speak with awe of the Mistress of the Copper Mountain, a witch whose dominion is the rocks they mine, though none have seen her. An elderly stone carver, Prokopyich (Mikhail Troyanovskiy), is such an expert craftsman that we’re told “no one knew the soul of stones better than he.” In thinly-veiled Communist messaging, he is exploited ruthlessly by the wealthy land owner and his brutal, whip-wielding bailiff. Prokopyich receives an apprentice, Danilo, whom he allows to wander idle, afraid that working with the stone and its dust will send him to an early grave. On one of these wanderings, Danilo becomes an object of interest for the Mistress of the Copper Mountain (Tamara Makarova), disguised as a lizard; while basking on a rock, she transforms into a woman in a slinky, glittering green dress. Years later, the land owner summons Prokopyich and demands he make a malachite box of such ornate design that it will win him a bet with the Marquis de Chamfort, whom he met on a recent trip to France. Working through nights to almost fatal exhaustion, the sculptor cannot complete the box; when the landlord arrives demanding the prize, Prokopyich is stunned to discover that the box has been completed by Danilo, who’s now a young man and a formidable talent (Vladimir Druzhnikov). The beautifully carved box bears the image of a lizard on its lid.

The journey into the mountain, with unfolding doors of stone.

Pleased with the box, the landlord’s wife demands that she make him a vase. Danilo pours his heart into the creation, working upon it as the months pass, and neglecting his girlfriend Katya (Yekaterina Derevshchikova) – in a lyrical sequence, she paces in sorrow beside a river and Ptushko holds the camera in place, watching the rippling water and the branches of the trees as the seasons pass before our eyes. When the vase is complete, Danilo reveals to Katya that she was the inspiration for its design, which is in the shape of a flower. But he has become obsessed with the legend of a stone flower in the domain of the Mistress of the Copper Mountain, an object of such craftsmanship that it teaches secrets of gem-carving mastery to the artisans who behold it – though he’s warned that the price may be to become one of her carvers, working in her mountain and forgetting all about “earthly life.” As he walks through the woods in the middle of the night, a hill of flowers suddenly bloom before our eyes and out strides the Mistress of the Copper Mountain, who promises he may see the Stone Flower when the first snow falls. This happens on his wedding day. Ptushko delivers one of his many frame-filling close-ups as the haunted Danilo stares off into the distance, and then leaves Katya’s side and strides past revelers, departing without anyone noticing. Ptushko delivers an incredible bit of production design as Danilo follows the Mistress from “Serpent Hill” into the mountain, where walls of rock part in all directions in a single shot as they penetrate further and further into its interior, the last lowering to form a bridge over a crevasse; then we see them walk through canopies of multicolored minerals until they finally reach the stone flower, which materializes before a vast wall of crystal. Danilo sets to work building a likeness of the flower within the mountain, while the Mistress falls deeper in love with him. Outside, the forlorn Katya drifts through life under the protection of the worried Prokopyich, until they are finally reunited as love breaks the spell.

The Mistress of the Copper Mountain (Tamara Makarova) reveals the stone flower to Danilo (Vladimir Druzhnikov).

The central triumph of the film is Ptushko’s ability to turn special effects into emotional expression, most notably in the hypnotic scene of Katya’s long summer and autumn separated from her lover, but also in the ecstatic blooming of flowers at midnight, or in a scene where Katya confronts the Mistress of the Copper Mountain who’s stolen Danilo from her, and the jealous sorceress waves her hand at a tree, which suddenly uproots itself and lowers across a chasm so she can cross and then vanish (the tree springs back up before Katya can follow). In further films, Ptushko would push these ideas even further, culminating in the four-year-long production Ruslan and Ludmila, whose subterranean tableaux are even more dream-like and stunning to behold. An oft-used criticism of special effects movies is that character and story take a back seat; in Ptushko’s films, beginning with The Stone Flower, they are fully in service, even if the characters are deliberately pressed into types, as fairy tales do: Danilo, the obsessive artist seeking perfection; Katya, mourning her lover. Ptushko is seeking the ultimate visualization of the fairy tale, which even extends to a scene that would become something of a trademark in his films: the gathering of woodland animals a la Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, often filling the corners of the frame with noses and tails twitching. He would stretch his mode into romances (Scarlet Sails) and epics (Ilya Muromets) and even whimsical fantasy in the context of the contemporary urban life (A Tale of Time Lost) – but always with a distinctive, vividly colorful, deeply expressive style that could only be the work of Ptushko.