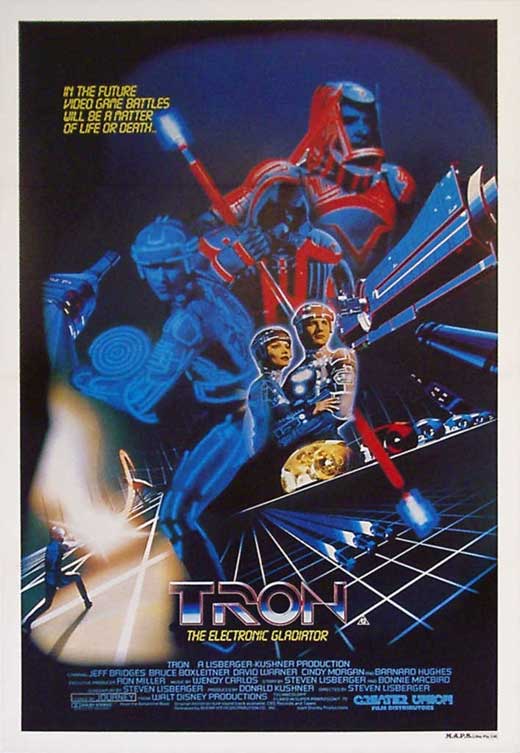

I was the right age when TRON (1982) was released. The ambitious Disney live-action/computer-animated spectacle may have been a financial failure, but I was too young to notice anything but the film and its merchandising: its completely unique look with those neon-highlighted uniforms and arenas. I was playing the Atari 2600 and begging my dad for quarters at the mall arcade, and here was a film which used the aesthetic of those early video and computer games to create a fantasy world where the competition could actually kill (or “de-rez”). I was a California Bay Area kid. In 1983 our family took a vacation to Disneyland, and while riding the “People Movers” with my mother – too scared to go with my sister and dad on Space Mountain or the Matterhorn, Tomorrowland’s electric tram was more my speed – I was dazzled when we passed into a dark space that suddenly, below us, transformed into the computer world of TRON, light cycles zipping across the landscape at right-angles. It may have been a shrug of a marketing move instead of a fully realized TRON ride, but for that half-minute or so the world of TRON became even more alluring. In its puffy, oversized Disney VHS case it became a favorite video store rental, and if the actual arcade cabinet presented an impossible challenge to play, at least with its aesthetics I could trick myself into thinking I enjoyed it while Dad’s quarters quickly vanished. The 80’s were a godsend for kids looking for escapism at the theater; Indiana Jones and Star Wars meant more to me. But it’s impossible to imagine my childhood without TRON.

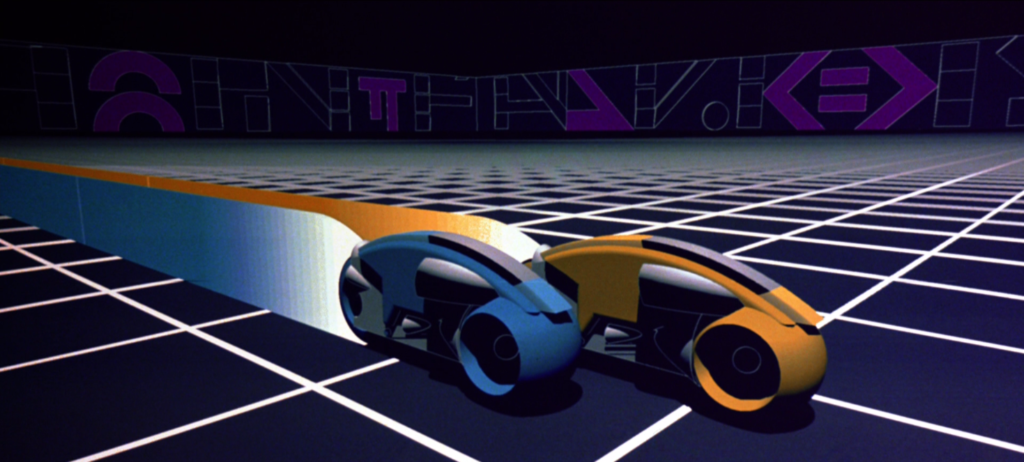

Light cycle racing in the opening minutes of TRON.

So – greetings, Programs! – you can imagine that watching the film today, there’s a thick swamp of nostalgia for me to wade through, watching scenes and listening to (not at all special) dialogue that’s been long since imprinted on me. Nonetheless, the film’s flaws are obvious even to a TRON nerd like myself. It’s been about twenty years since I watched it last, and I was floored by how clumsily the film opens. After a spectacular opening title, the single word spinning and overwhelming us as we dive into animated computer circuitry, we skip jarringly from one moment to another. The sinister program Sark (David Warner, as evil as he is in the previous year’s Time Bandits but nowhere near as funny) reports to the giant face which is the MCP (Master Control Program). Video athletes whom we haven’t properly met compete in a light cycle race. Essentially, the film – eager to assure us that there will be a lot of cool stuff in this movie, don’t you worry – spoils its fantasy world and does so with choppy editing and a confusing narrative. Imagine how much of the magic would have been drained if The Wizard of Oz began in Oz, in color, to discuss the state of the Emerald City, and then switched back to black-and-white Kansas to meet Dorothy. An awkward “Meanwhile, in the real world…” intertitle, the likes of which will never be repeated in the film, transitions us to the story proper, as we meet programmer Alan (Bruce Boxleitner), an employee of the vaguely sinister ENCOM. Alan has designed an all-encompassing company security program which is concerning to its Senior Executive VP Ed Dillinger (Warner), who consults with the MCP – a domineering artificial intelligence which is swallowing up intellectual property from other companies and blackmailing him to comply with its plans. Alan’s girlfriend Lora (Caddyshack‘s Cindy Morgan) is working on another ENCOM project with Dr. Walter Gibbs (Barnard Hughes) which can digitize matter, which is important to me, because the film is barely about that. Upon learning from Dillinger that someone’s been trying to hack ENCOM, Alan and Lora seek out the #1 suspect, their friend and former co-worker Flynn (Jeff Bridges), who owns his own arcade that features the video game he designed while at ENCOM, Space Paranoids. Flynn cops to hacking the company, trying to uncover some material evidence that he designed many of ENCOM’s hit games – and this is the focus of the plot. Not the fact that Lora and Dr. Gibbs have essentially invented teleportation. No, this is a story about receiving proper credit and earning residuals.

Alan (Bruce Boxleitner) and Flynn (Jeff Bridges) discuss hacking ENCOM.

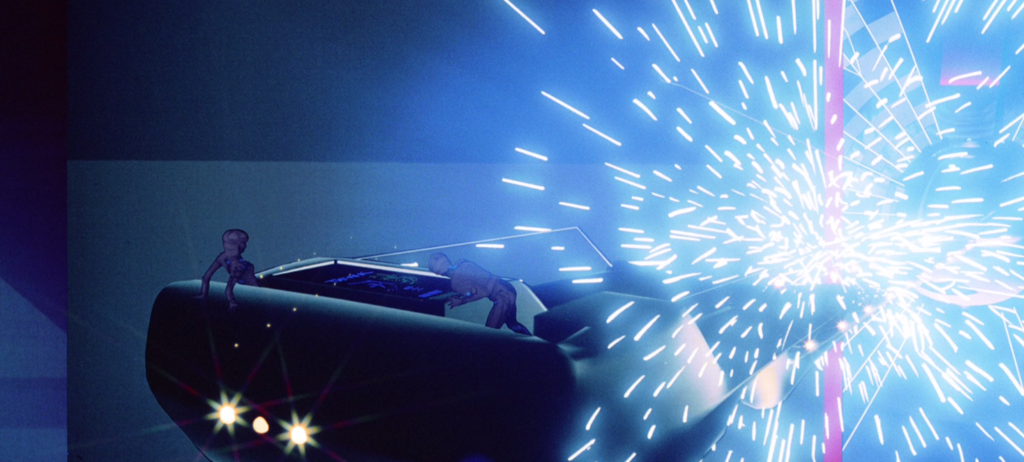

I’m being a little unfair. TRON is prescient in many ways, including the fact that the MCP gains more power by stealing technology from other companies, a tactic that has become more common in the online world. The idea of MCP/ENCOM growing and growing by greedy acquisition also foreshadows Amazon and (gasp!) Disney. And it’s fun to realize how common the terminology of TRON is today, when it seemed like so much esoteric computer-babble in its time: we don’t have to think hard about the role of a security program, why one character is called Ram, or why the floating binary bit can only answer questions in yes or no; even the terms “program” and “user” weren’t in everyday use in 1982, at least among people who weren’t computer geeks. Director Steven Lisberger, who had previously directed animation, wanted to make a thoughtful science fiction adventure which reflected, as accurately as possible in this fantasy context, the state of computer programming in the early 80’s. That’s interesting as far as it goes, but the film’s strengths lie in its surface pleasures, which are considerable. Once Flynn is digitized by the MCP-controlled laser and converted into a digital character, the film transforms from a Brainstorm-style computer conspiracy thriller into authentic cyberpunk. This transition occurs with a trippy 2001-style voyage into the computer which must have looked spectacular for those who saw the film in 70mm. To film the computer world, the actors were shot in black-and-white wearing circuitry-inspired costumes designed by the legendary French comic book artist Moebius (aka Jean Giraud), with black strips of tape on their uniforms lit up in post-production to become glowing streaks of light. With their faces still monochrome, and their bodies rendered with fuzzy boundaries as they walk through bluescreened environments, the effect is eerie. The landscapes were designed by Syd Mead, who was having a big year thanks to his extraordinary work on Blade Runner. Some of the computer realms, particularly in a late-film voyage via the “solar sailor,” look like prog rock album covers. And a jai alai battle inspired by games like Pong and Breakout is genuinely suspenseful.

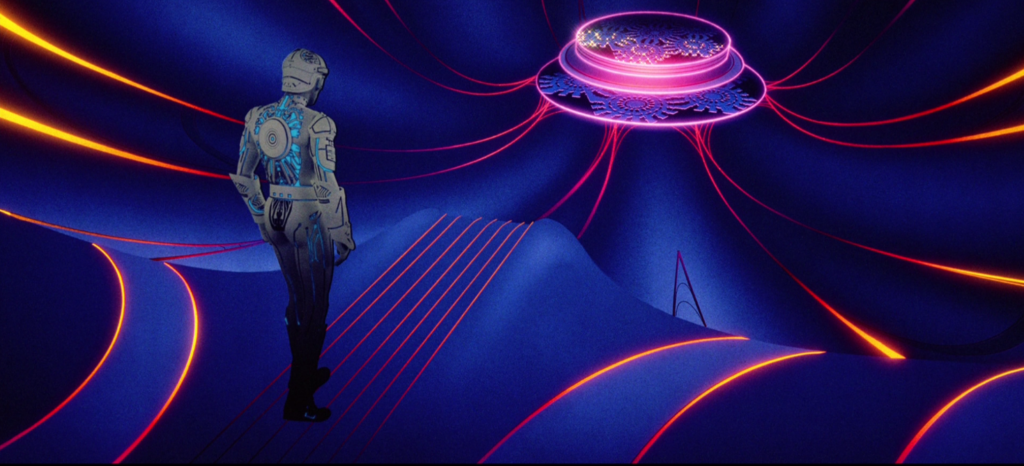

The fugitive security program Tron (Boxleitner) explores the computer world.

The computer animation was groundbreaking for its day. Consider how far the technology advanced from the Death Star destruction simulation reviewed inside the Rebel base in Star Wars to the brightly-colored, shaded contours of the light cycle races here. They still hold up very well for one important reason: they’re not meant to look real, but to represent an up-close, three-dimensional video game. Importantly, the entire film is not computer-animated (that wouldn’t have been possible at the time), instead employing a variety of techniques to fool the eye into not quite understanding what it’s seeing, forcing you to buy into the illusion. It’s also visually arresting, on an MC Escher level, that from scene to scene we “users” can’t easily discern solid from empty space, where someone might cross a transparent bridge or drop into eternity. The electronic score by experimental musician Wendy Carlos is perfect: offbeat, slightly queasy, and always with one foot in the sounds of an arcade game. Still, the world-building is glaringly insufficient. In later scenes where the fugitive programs Tron (Boxleitner) and Yori (Morgan) explore a city, we’re just greeted with a variety of strange characters posing or stiffly talking to each other; there doesn’t seem much for these programs to actually do in their downtime. Where do they live? What are their goals? We do learn that they can drink energy, as – in a nice moment – Flynn and his fellow escapees discover a secret river of the stuff in its purest form. We also learn that the programs live in worshipful awe of their “users,” which is weirdly uncomfortable as they come to realize that Flynn is one of those god-like beings. It’s even more uncomfortable when Flynn locks lips with Yori, who bears the image of his ex-girlfriend in the real world. What does she or her avatar mean to him? What is he thinking? (I’m resisting the urge to analyze all this – I really, really want to – but TRON barely gives these topics any thought.) Only one funny moment, when an insurance actuarial program begins to speak in the sales pitch of its user, offers a glimpse of the wit and fleshed-out details another script draft might have given us: “Of course, if you think of the annuity as a payment over the years, the cost is really quite minimal.” The characters are all flat as pixels with the exception of Bridges, who shoehorns his trademark sly charm to give the film just enough of the human to provide the necessary contrast with the virtual.

Battle on the solar sailor.

The film arrived during a directionless period in Disney’s history, when many of their films were released in a confused state, notably in the “horror flick or kid’s movie?” items The Black Hole (1979), The Watcher in the Woods (1980), Something Wicked This Way Comes (1983), and the PG animated The Black Cauldron (1985). The trajectory became familiar: start with an ambitious project with a bit of edginess, then check it with nervous second-guessing. Of this period, perhaps TRON shines brightest, because despite its flaws it is the least compromised. Disney really hoped this would be its Star Wars, and invested in its cutting-edge approach to fantasy filmmaking. The film may have flopped, but its pop culture impact cast a much longer shadow, such that the property was resurrected for a light cycle theme park ride in Shanghai Disneyland and a big-budget sequel, TRON: Legacy (2010), which my niece holds up as one of her favorite films. I’m due to rewatch TRON: Legacy. When I saw it in the theater, I loved the Daft Punk soundtrack and the updated visuals, but was disappointed that the story did little more than act as a nostalgic tribute to the original. We’ve become such an online, technology-focused society, shouldn’t the story be updated to reflect the new super-connected, cyberpunk world we’re all living in, and apply its science fantasy from there? Instead, the 1982 world of the MCP is preserved on its original hard drive, so we can see how the environment has aged. Given how much nostalgia colors my feelings for the Lisberger film, perhaps I shouldn’t be protesting that approach.