Two traveling newlyweds, Stefan (John Karlen) and Valerie (Danielle Ouimet), arrive by train to Ostend on the northern coast of Belgium in the off-season. The ocean churns against a desolate beach, and the cries of seagulls slice crisply through the wintry sky. Waiting for a boat back to England where Valerie will be introduced to Stefan’s mother, the couple check into a luxurious old hotel, deserted aside from a long-serving clerk, Pierre (Paul Esser), and select the royal suite. That night, two women pull up their car to the front of the hotel. “Let’s hope we’ll find something better here,” says the younger of the women. “I’m so tired.” The vintage car, their makeup, their hair – they look like they’ve arrived from an earlier era. In particular, the younger woman, Ilona (Andrea Rau), with her large eyes and black bob, resembles Louise Brooks of Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl. The elegant older woman, in her black veil, bears an uncanny resemblance to Marlene Dietrich in Shanghai Express; her name is Countess Elizabeth Bathory. Pierre recognizes her from forty years prior, and is stunned that she hasn’t aged a day. “My mother, perhaps,” says the Countess. Setting eyes upon the young couple dining alone and learning that they’re occupying her preferred room, she’s only delighted. Of course she’s an immortal Hungarian vampire. But she has style and interests. She’s a grande dame in her own imagination, a Norma Desmond of vampirism, and she does more than just drink blood. At her best, she seduces and destroys as an art, and this couple, already showing signs of complex dysfunction, present a fascinating challenge.

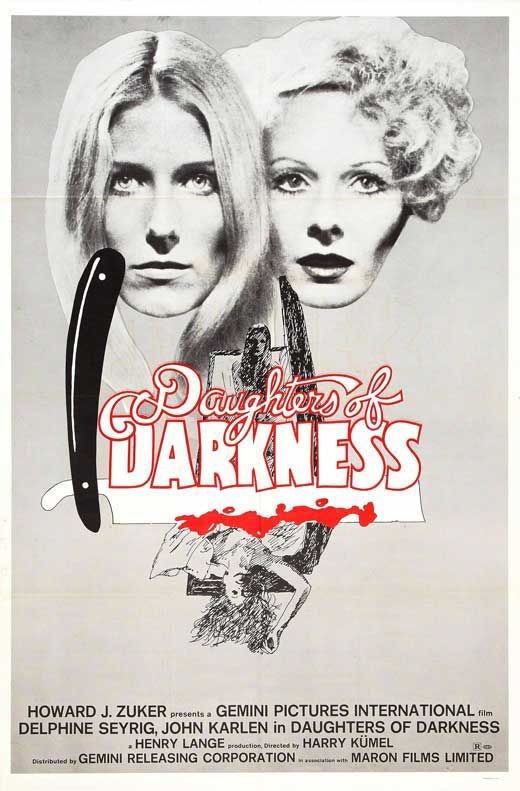

Newlyweds Stefan (John Karlen) and Valerie (Danielle Ouimet) are joined by the spectacular Countess Bathory (Delphine Seyrig, center).

Daughters of Darkness (Les lèvres rouges, 1971) is directed by Harry Kümel, the Belgian filmmaker who would go on to direct the cryptic fantasy Malpertuis (1972) with Orson Welles. In addition to its location shooting – the canals of the beautiful tourist town Bruges are briefly visited, and the hotel interiors were shot in Brussels – the film has a style which owes as much to Belgian Surrealism (Magritte in particular) as the visual panache of the country’s comic books; a moment in which Bathory hands over her mysterious green drink to Pierre, who discreetly but promptly dumps it into a potted plant, has the elegant wit of a Tintin comic. But Kümel, assisted by co-writers Pierre Drouot and Jean Ferry, doesn’t skimp on the sex and violence, and fused with the film’s humor and mystery this becomes a distinctive moment in the proliferation of sex-vampire movies in the early 70’s, perhaps the genre’s high watermark. There’s enough blood to make Kümel’s decision to fade to red, rather than black, simply inevitable. But all the scenes featuring exposed flesh have a naturalism and vulnerability that rise above mere exploitation; never more so than in a chaotic struggle inside a hotel bathroom which anticipates the raw, awkward realism of the sexual violence in George A. Romero’s Martin (1977). Daughters of Darkness is complicated, contradictory, and messy in the way that human beings often are. After an opening sex scene in the train compartment, Valerie and Stefan tell each other, reassuringly, that they are not in love. Pierre, who is hiding a secret about his mother and is persistently delaying their departure for England, has an overt sadomasochistic side. In bed, he whips Valerie with his belt. When he sees the body drained of blood in Bruges, he throws Valerie to the ground in his efforts to get a closer look at the corpse being carted away. On the ride back to their hotel, she accuses him, “It gave you pleasure. You actually enjoyed seeing that dead girl’s body.” He replies coolly, “And you enjoy telling me. We’re getting to know each other.”

The married couple.

However, the shadows within Stefan are soon eclipsed by a more experienced practitioner of darkness. Valerie, having grown dismally accustomed to Stefan’s domineering, chauvinist attitudes, views an overture from Bathory as irresistible. Suddenly Stefan, who once seemed to contain mysterious multitudes, now becomes pathetic, small, and desperate. Even the beautiful, porcelain Ilona, the servant of Bathory for an untold period of time and who’s started to chafe at the role, flares with jealousy when she sees Bathory lasciviously courting the new young playthings. It is Bathory who is always in control, and even when an unexpected tragedy occurs, she adapts swiftly and uses the situation to her advantage over Valerie and Stefan. Delphine Seyrig, an acclaimed actress who had worked with Resnais (Last Year at Marienbad), Truffaut (Stolen Kisses), Buñuel (The Milky Way), and Demy (Donkey Skin), makes her surprise debut in the horror genre as a fearless and indispensable performer: she twists the film into her orbit, just as Elizabeth Bathory would. She does not play the role as “vampire,” despite the film’s frequent allusions to Bram Stoker. Her Bathory is a force of confidence, endless charm, and merciless precision. To accept her “red lips” (the film’s original title) offers a somewhat different attraction than from cinematic vampires past: wouldn’t you want to be as effortlessly self-possessed as the Countess? To always enter a room as if you’re a star? Only the empty wintertime resort, the gloomy skies, and the weary voice of Ilona – “I’m so tired” – offer hints of the emptiness of immortality, the limits of pursuing pleasures eternally, the glamor starting to fade.

Note – Daughters of Darkness is currently available on DVD and on Amazon Prime, but in a couple months Blue Underground will be releasing the film in UHD and Blu-ray, restored from a 4K scan of the original 35mm camera negative, along with a CD of the film’s superb score by François de Roubaix.