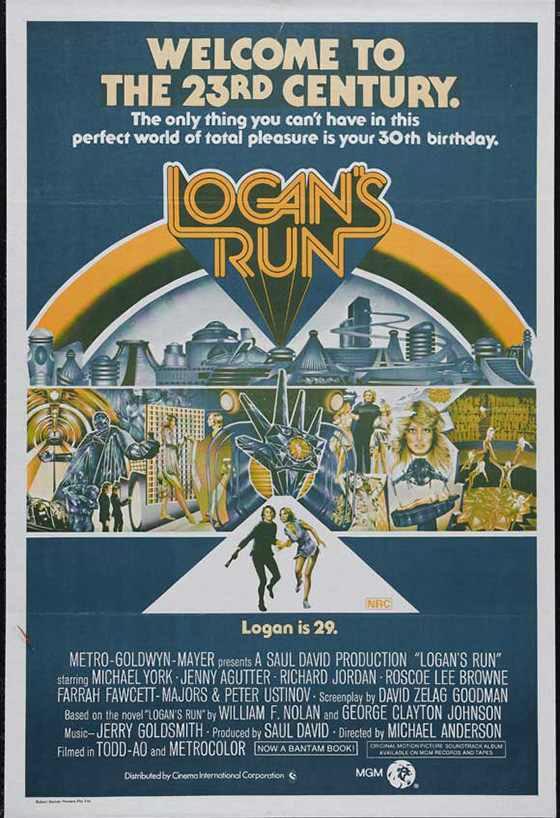

It seems that people like to view Logan’s Run (1976) as the last of its kind: a disco-glitzy, frequently silly science fiction spectacle that would go extinct the following year with the arrival of Star Wars (1977) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), the superior genre species. And while it’s true that George Lucas and Steven Spielberg were setting new, glossier standards for science fiction and fantasy, it’s a bit revisionist to think that a page was turned and there wasn’t plenty of cheesy science fiction in their wake; in fact, the success of Star Wars gave us a glut of what might be called Disco SF: Starcrash (1978), Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), and other New World productions, as well as TV shows from Battlestar Galactica (1978-79) and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century (1979-1981) to The Star Wars Holiday Special (1978). Nonetheless, it does feel like Logan’s Run closes the door on an era. For all its gaudy glamor, wobbly, shiny robots, and the presence of Farrah Fawcett-Majors, its serious plot aligns itself with science fiction films from earlier in the decade: pictures like Silent Running (1972), Soylent Green (1973), and Rollerball (1975). It has more philosophical interests than the post-Star Wars films, and it’s not afraid to get dark. For all its special effects and sex, it’s not escapism; and despite the indelible mark it left on many adolescent boys (ahem – Jennifer Agutter), it’s not juvenile.

Jennifer Agutter as Jessica.

It does open with a gloriously fake-looking model, which the “kit-bashing” of Star Wars would put to shame. As the credits roll, a camera swoops in on an HO-scale domed city, with shining pools of blue water, futuristic buildings, and monorails. The set itself is basically a science fiction version of the Mall of America, with escalators, neon-sign shops (change your face at “The New You”), hand-holding twenty-somethings and frolicking children, all dressed in brightly-colored togas of yellow, green, and red, denoting their age. Every citizen has a red crystal embedded in the palm, a timer that will go off at the age of 30, at which point he or she will be ushered into an arena to undergo the ritual of “Carrousel.” This involves wearing a white mask and a bodysuit, floating into the air, and then exploding into sparks and fire. Supposedly, they will be reborn, to follow the cycle again. In fact, this is a form of population control. Outside the dome is a world ravaged by old wars and pollution, but those inside the domed city live a short life centered around shopping and sex, perfectly safe, perfectly controlled by the mechanized city. If you decide to flee and become a “Runner,” you’ll be hunted and killed by a “Sandman.” And one must assume there are lots of Runners, because there are a lot of Sandmen.

Michael York as Logan.

Two of the Sandmen are Logan (Michael York, The Three Musketeers) and Francis (Richard Jordan, Dune), who laugh and joke with one another as they leave Carrousel to hunt and kill a Runner. (You’ll notice that throughout the film Logan is a terrible shot, and a pretty incompetent Sandman. Take a drink each time he misses when his target is only standing a few feet away.) Later, Logan uses a Star Trek-style teleportation device to cycle through potential sexual partners for the evening, and settles upon Jessica (Agutter, Walkabout), who wears an ankh at her neck and expresses hesitation about having sex with a man who kills Runners for a living. When Logan is summoned to the master computer that runs the city, he learns that the ankh is a symbol for “Sanctuary,” a legendary place outside the city where many Runners have fled. He is tasked with going undercover as a Runner, and his lifespan is shortened by the computer, his crystal flashing red to indicate he’s 29. Logan tries to earn the confidence of Jessica, but she isn’t swayed until she witnesses him allowing a Runner to go free. With Francis dogging their heels, they embark on a journey through the New You plastic surgery clinic, a slow-motion psychedelic orgy, and finally through tunnels and sewers into the outer reaches of the city, where in an ice cave they’re threatened by a food-gathering robot named Box (Roscoe Lee Browne, Super Fly T.N.T.). Outside, they cast their eyes upon the sun for the first time (a la THX-1138), go skinny dipping, and travel to the ruins of Washington D.C., where they meet a lonely old man, played by the great Peter Ustinov.

Jessica and Logan meet the robot Box, voiced by Roscoe Lee Browne.

By this time, Logan has switched his allegiance and is no longer interested in reporting on Sanctuary to the master computer – but the film does a poor job of indicating just when this change of mind occurs. In fact, it’s one of the film’s central weaknesses that the title character remains something of a cipher. But character development is not the film’s strong suit: Agutter is lovely, but she’s given a character without much depth; even Ustinov isn’t given very much to work with. Worst of all, the film’s climax is simply lazy: Logan tells the master computer that there is no Sanctuary, and the computer promptly short-circuits and blows up the entire city. (The master computer is…touchy.) Many of the concepts, such as an Escape from New York-style facility for juvenile delinquents, seem only half-realized or inadequately explained. Regardless, the expansive sets are shot to maximum effect by director Michael Anderson (Around the World in 80 Days, Orca), and many of the matte paintings are spectacular, particularly those of a vegetation-choked Washington D.C. The domed city of pleasures looks like the sort of place that would be fun to visit, despite the sinister Westworld edge. And there’s an interesting, Barbarella-style eroticism to the film, with Agutter – most recently seen kicking ass in Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) – wearing a diaphanous green toga that’s increasingly abused (soaked, ripped) throughout the film’s two-hour running time. The periodic nudity would easily earn the film an R rating if released today, but by 1976 standards it was only a PG – thus the impact to the imaginations of young boys everywhere. The screenplay, by David Zelag Goodman (Straw Dogs), is adapted from the 1967 novel by William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson (itself followed by many sequels). My memory of the novel is vague, except that this is a loose adaptation. Jerry Goldsmith (Planet of the Apes) provides the score, and the special effects – which are spotty at times – won an Oscar. A short-lived television series of the same name arrived the following year, and remakes have been discussed in recent decades, though none have yet materialized. In retrospect, it’s easy to admire the ambition of Logan’s Run. If it falls short of the mark, at least it goes big, and it’s seldom boring.