Carried away on a flying carpet by her hero, the Scarlet Falcon, the beautiful Lida asks, “Where are you taking me?” He replies, “Wherever you wish. The court of the great Khan, the Pillars of Hercules, Constantinople, Rome, the mountains of the Moon.” Modern audiences might think it a scene straight out of Disney’s Aladdin, but it was just another Arabian Nights programmer; at least a handful were churned out of Hollywood every year straight through the 1960’s. The disposable film in question, The Magic Carpet (1951), was produced for Columbia Pictures by Sam Katzman, who specialized in B-movies and serials, and in the same year was attached to projects like the Jungle Jim entry Fury of the Congo, the George Washington historical fiction When the Redskins Rode, and the 15-chapter Captain Video, Master of the Stratosphere. Alongside his many monster, swashbuckler, and teenage rebel movies, he would produce further Arabian Nights pastiches, including Thief of Damascus (1952), Siren of Bagdad (1953), Prisoners of the Casbah (1953), The Wizard of Baghdad (1960), and – if it counts – Elvis Presley’s Harum Scarum (1965). The Magic Carpet, directed by journeyman filmmaker Lew Landers (who had made The Raven with Lugosi and Karloff, and would direct Aladdin and His Magic Lamp the following year), was smart enough to spell out its best promise to matinee-devouring kids right there in its title. If nothing else, you’ll get to see a flying carpet. Another key attraction for kids and families was that it was in color – Supercinecolor, to be precise, a three-color process which had debuted that year and would be used in films like Jack and the Beanstalk (1952) starring Abbott and Costello and the 3-D science fiction pictures Invaders from Mars (1953) and Gog (1954).

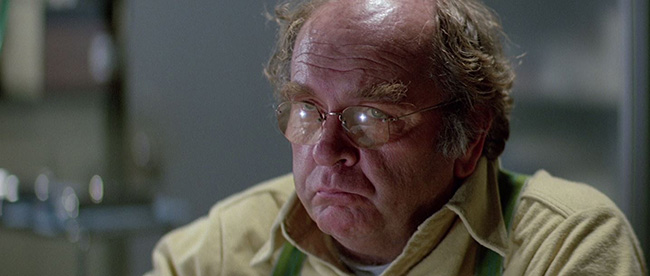

Caliph Ali (Gregory Gaye) and his sister, Princess Narah (Lucille Ball).

Landers keeps the pace pleasingly fast, squeezing this whole epic fairy tale into 83 minutes. In the opening scene, a good caliph is usurped by an evil one, Ali (Gregory Gaye, Ninotchka) and his chief strategist, the Grand Vizier Boreg al Buzzar (played by Perry Mason himself, Raymond Burr). The one true heir to the throne, Abdullah al Husan, is just a babe, and he’s placed on a flying carpet which spirits him away over the city. When he grows up, he doesn’t know the nature of his inheritance, but he begins harassing the Caliph Ali under his secret identity the Scarlet Falcon, dressed entirely in red. He’s now played by John Agar (She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, Sands of Iwo Jima), making a stock, square-jawed hero, and one as American as they come, of course. Agar is joined in his insurgency by stubborn and fiery Lida (Patricia Medina, who would go on to Aladdin and His Lamp and Siren of Bagdad) and faithful Razi (George Tobias, Sinbad, the Sailor and later of Bewitched). Lida is an unusual love interest for a 50’s adventure film because she can hold her own and isn’t a damsel in distress; in an early battle scene, she smashes down her opponents with a flaming torch. They both go undercover in the palace: the Scarlet Falcon as a physician who cures the Caliph of his hiccups (!), and Lida as a harem girl – Medina has the honor of delivering the token bellydancing sequence. But our hero is found out by the Caliph’s scheming sister, Princess Narah, played by, of all people, Lucille Ball. Ball was a busy actress, making a handful of films a year in different genres (including the classic noir The Dark Corner), and getting laughs on the popular radio program My Favorite Husband, but she was only on the cusp of becoming a queen of comedy: I Love Lucy would begin airing just three days before The Magic Carpet hit theaters. Here, her role is surprisingly small, and despite her sassy line readings, she isn’t given anything comedic to do. If she’s miscast, it’s almost by accident. Ball owed Columbia one more film, and was offered the small part by Columbia president Harry Cohn in hopes that she would turn it down so he could avoid paying her large salary; but Ball – whose big name would appear beside Agar’s on the film’s posters – accepted the part, expecting to fulfill her contractual obligation quickly so she could take a much bigger role for rival Paramount (in The Greatest Show on Earth). That never came to pass, because she discovered on the set of The Magic Carpet that she was pregnant. As it happened, I Love Lucy became a huge hit, and defined the rest of her career – making the contemporaneous The Magic Carpet seem all the more like a strange aberration.

Caliph Ali’s harem. Fresh towels are available at the front desk.

Apart from Ball’s unexpected presence, there’s little to distinguish The Magic Carpet from the dozens of other Arabian Nights adventures from the 50’s, but there’s plenty of kitsch value. Caliph Ali’s harem is filled with beautiful women in harem costumes (which don’t show their belly buttons, as decency, or perhaps the Production Code, requires), and he also has a clamshell-shaped swimming pool, which looks exactly like a 1951 pool in a fenced-off backyard somewhere in the Hollywood hills. Here, the girls splash around and frolic. In a brief scene, Medina disguises herself as a boy, despite the fact that she’s wearing a layer of makeup and bright red lipstick. Signs about the Arabian city are written in the expected “Arabian Nights” lettering style but are in perfectly legible English. The scimitars seem a bit wobbly at times, and the costumes and sets look re-used many times over. As for the flying carpet, Katzman and Landers borrow from the Douglas Fairbanks Thief of Bagdad playbook, and create a carpet that’s a platform which can be suspended and swung around on (effectively disguised) cables. During these scenes, Agar strikes his best Fairbanks pose and grins, holding on tight while it hovers across the set. At one point he even intercepts a carrier pigeon! But if you look closely at the end of the film when it lifts Agar and Medina out of the city, life-size models are swapped out for the actors (fairly convincingly), so the stunt isn’t as risky as what Fairbanks pulled off back in 1924. For even wider shots, an obvious miniature is used against a painted backdrop. Although this is the sort of film that Ray Harryhausen deliberately sought to enliven and revise with the landmark The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), the formula is reliably entertaining, which is why they made so very, very many of these.